Rybolovlev, Sotheby’s and an Alleged Billion Dollar Blow Out

A Russian multi-billionaire is seeking justice after overpaying for artworks. Sotheby's is the defendant, but the art market's opacity is also being questioned.

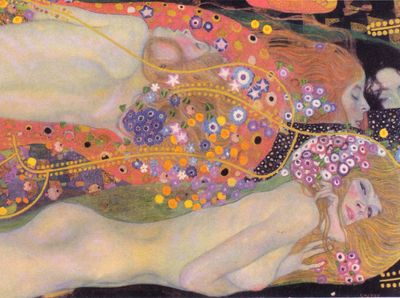

Gustav Klimt's Water Serpents II (1904–1907) (detail). Oil on canvas. 80 x 145 cm. Public domain. Rybolovlev reportedly grew suspicious of art dealer Yves Bouvier after learning Sotheby's sold the painting for U.S. $120 million in 2012, when he paid Bouvier $183.3 million for it that same year.

Art news media can't get enough of Accent Delight International (ADI) v. Sotheby's, a trial now underway in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York.

ADI is the company used to buy art by Russian multi-billionaire Dmitry Rybolovlev, who made most of his wealth in the fertiliser trade and spent a fraction of it purchasing a majority stake in football club AS Monaco.

Rybolovlev bought 38 works for around U.S. $2 billion over 12 years through Swiss dealer Yves Bouvier—a major player in the murky world of free ports. He now claims he overpaid by up to $1 billion. (Sotheby's was involved in 12 of the sales, but only four are cited in the lawsuit.)

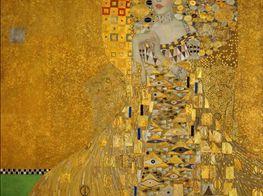

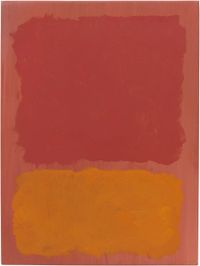

Rybolovlev unsuccessfully pursued criminal charges against Bouvier in France, Monaco, and Switzerland, claiming that the art dealer bought works by artists such as Amedeo Modigliani, Gustav Klimt, and Mark Rothko and marked them up tens of millions of dollars when Rybolovlev was under the impression Bouvier was acting on his behalf.

They settled out of court in December. The terms of the settlement have not been disclosed.

Rybolovlev is now accusing Sotheby's of facilitating Bouvier's deceptions by vouching for the works and providing inflated appraisals of their worth.

On the stand, Rybolovlev said he was betrayed and taken advantage of.

'Sotheby's makes it difficult for people like me, who are experienced in business, to know what's going on,' he said. 'It's important for the art market to be more transparent, because as I've already mentioned, when the largest company in this industry [Sotheby's] is involved in actions of this sort, clients don't stand a chance.'

Under cross-examination, lawyer for Sotheby's Marcus Asner repeatedly asked Rybolovlev about the expertise he engaged in his business dealings, implying he should've done the same as an art collector, or at least managed his relationship with Bouvier much more carefully.

'Mr. Rybolovlev, are you familiar with the term "the buck stops here"?' Asner asked.

Asner also questioned Rybolovlev's commitment to transparency. The collector has both bought and sold works anonymously, and pretended not to be interested in Leonardo da Vinci's Salvatore Mundi (ca. 1500) to bring down the price.

'Were you being transparent here? Is it okay for you not to be transparent?' Asner asked.

That argument seems disingenuous. Given the art market's opacity, for Rybolovlev to be completely transparent would make him a mark.

Noting that the art market is opaque and unfair hardly proves that Sotheby's defrauded Rybolovlev, but it does expose some of its ugliness. —[O]