Shilpa Gupta Complicates Nation-state Notions in U.S. Survey

The Mumbai-based artist discussed her strategies for challenging countries' conceptions of boundaries—both real and figurative.

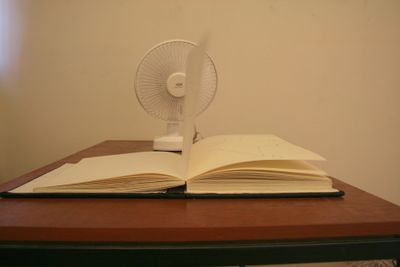

Shilpa Gupta, For in Your Tongue I Cannot Fit (2023). Exhibition view: I did not tell you what I saw, but only what I dreamt, Amant, New York (21 October 2023–28 April 2024). Courtesy Amant. Photo: Daniel Wang.

'How is it that all the countries tell their citizens they are the best?' Shilpa Gupta asks, quoting a line from Benedict Anderson's Imagined Communities.

It's a question that relates to her practice. Divided into competing nationalities, how can we all share the same space and engage in dialogue?

Over a cup of tea, Gupta shared motivations behind her work and how she hopes audiences will engage with her mini survey exhibition, I did not tell you what I saw, but only what I dreamt (21 October 2023–28 April 2024) at Amant, New York.

Most of the pieces shown at Amant, says Gupta, have lived a life of their own, having previously been showcased in contexts across the globe. What intrigues Gupta is the challenge of adapting them to their local contexts, since she's preoccupied with identifying certain patterns—state assertion, collective memory, and shifting geopolitical borders—that repeat globally.

Adapting to the U.S. context, Gupta is showing a new rendition of 100 Hand-Drawn Maps of my Country, a project initiated in 2008 which invites individuals from various global contexts—Mumbai, Cuenca, Delme, Gwangju, Seoul, Cheorwon, Tel Aviv, Jerusalem, Montreal, and different parts of Italy—to create hand-drawn maps of their respective countries.

In this latest iteration, titled 100 Hand-Drawn Maps of the USA, 2023, Gupta worked closely with Amant's team, inviting schools and communities surrounding the exhibition venue to sketch a map of the United States solely from memory.

The act of relocating these maps to the contexts in which they are displayed is a crucial element of the work, Gupta explained.

'It's important because we're dealing with images that the viewer knows well, but typically regards as static and unchanging,' she said.

No single drawing made by the participants is entirely accurate, and no two are alike. States are often forgotten, distorted, or merged with others.

Gupta notes, 'It's only when you see these shifts and alterations in the drawings that they evoke an emotional resonance. This brings forth a certain disparity between private and public memory, between the officially sanctioned cartography and the informal mental image one holds of their country.'

These shifts and transformations, as identified in Gupta's work, occur at a particularly critical juncture of geopolitical strife, where nation-states worldwide—including Russia, China, and Israel—are contesting borders on land and at sea. Gupta has her finger on the pulse of an enduring crisis, and she's interested in untangling and addressing the power dynamics at play.

I did not tell you what I saw, but only what I dreamt prioritises the role of language as a means of control. For, In Your Tongue, I Cannot Fit, (2023), for instance, is an installation consisting of 100 books encased in gunmetal on bookshelves. The books bear excerpts from poets of different eras and nationalities who have endured state-sanctioned imprisonment, execution, or exile.

Transformed into unyielding metal monoliths, these books are impossible for viewers to open and read, a poignant reminder of the shameful practice of censorship.

For her U.S. audiences, Gupta activated the work by inviting New York-based poets such as Madhu Kaza, Lynn Xu, Pamela Sneed, and Sara M Saleh to read poems by contemporary and historic writers who have faced bans, censorship, or imprisonment. The event also included readings by Salil Tripathi, with whom Gupta published a book bearing the same name, reproducing all the poems that remain out of reach within the installation.

When asked what she hopes people take away from her work, Gupta expresses her desire to create a space for listening.

'It's not my aim to proclaim instantaneous changes, but rather to provide a space for possibility. The ability to listen, I believe, is the starting point for something,' she said.

Gupta acknowledges the challenges that lay ahead, situating her practice in an ongoing struggle.

'For now, we need to be able to keep standing and hold space for the next generation to continue with the work. This time, we need to be prepared for a very long haul.'

At the heart of Gupta's practice is a desire to provide agency—to make space, however minute, for people to pause and contemplate. In Untitled, (2023), a new commission at Amant, Shilpa dissects national flags into discrete symbols and blocks of shapes, some of which bear striking resemblances to one another.

Similar to a set of wooden blocks reminiscent of a Jenga game, the artist invites visitors to assemble and rearrange the pieces, creating new configurations that blur or reimagine the original geopolitical relations.

At a time when liberal imagination is under threat by oppressive state forces that continually assault our collective memory, Gupta's work introduces an element of open-endedness, suggesting that there is room for fluidity and creative reinterpretations. —[O]