Beatriz Milhazes

Beatriz Milhazes is one of Brazil's best-known female artists. For over three decades, the artist has been seducing art lovers and collectors with her vivid, kaleidoscopic, festive paintings and collages. Her work is sensual and unapologetically feminine, reappropriating and recontextualising the decorative and folksy, long derided in the art world and dismissed as low-brow. The surfaces of her collages and paintings burst with scatterings of flowers, but her arrangements aren't polite or orderly, or decorative. What emerges from Milhazes' work is a fecund and untamed tropical forest of trees and plants often layered atop each other. They hit you with their colour, shape, and dizzying configuration of patterns, a loud jungle of assorted papers and layered motifs vying for attention. In recent years the artist has moved to more geometric compositions, a return to the influences of Brazilian modernists like Tarsila do Amaral and Hélio Oiticica, and Op Art work of Bridget Riley. This adds yet another layer of movement and complexity to her pieces, figuration and abstraction brought into a harmonious, yet noisy, union.

The energy of her home city, Rio de Janeiro, is palpable in her joyous display of colour, calling to mind the city’s ‘carnaval’ with its throbbing music, elaborate head-dresses, and costumes. Dressed simply in a monochromatic ensemble and sporting a collection of bad-ass heavy gold rings on each finger, the pint-sized and exuberant Milhazes walked us through her White Cube exhibition in Hong Kong, where densely layered, vibrantly colourful works were shown in 2015.

Your work process seems to be quite laborious and complex. Can you explain how you create your paintings? And how this working process came about?

I only started making collages in 2003, but my technique for painting developed in 1989 and the process always had a connection with collage concepts. I would work with cutouts of paper and fabric on canvas, but in 1989 I had a crisis of how to express myself and I started researching different methods of painting using the monotype process, which drove me to this process of transferring onto canvas. I make a drawing on a clear plastic sheet and on the other side I paint a motif. Once the paint is dry I can peel off the images from the plastic and glue them onto the canvas and layer them—there is a connection with the collage process. I developed my own motif, drawings, and elements.

The difference with monotype and my technique is that monotype works with wet paint, and this works with dry paint. Sometimes bits of paint flake off and it looks a bit more rustic.

Can you elaborate on some of these motifs?

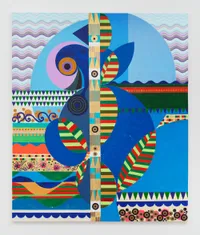

In my recent works I used abstract art as a reference and motif and element to the construction of the work. In the show at White Cube, you can see a dialogue between the leaves, botanical motifs of flowers, and trees sharing space with more geometric elements.

I use imagery from applied, decorative, or primitive art—naïve art—which has always motivated me to work with nature. I observe real nature. My studio is next to the botanical gardens. As an artist, as a person actually, I need to be close to nature. I was born in Rio de Janeiro, I grew up there and my studio is still there. We have a real nature—ocean, forests . . . But it’s only in the last five or six years that I have really absorbed these observations and influences in my work.

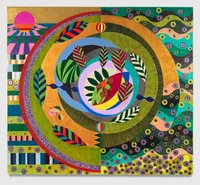

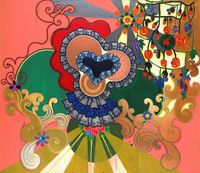

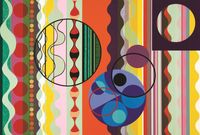

Exhibition view: Beatriz Milhazes, White Cube, Hong Kong (13 March–30 May 2015). Courtesy White Cube. Photo: Vincent Tsang.

Do you have a fixed idea of how you want the work to be, or is the process much more organic?

I always introduce new elements to my work, so I have a group of existing things and motifs and then I introduce some new ones, and they create a change reaction that will open new doors, allowing me to move forward. For the exhibition in Hong Kong, I started working with some preexisting cutouts that I already had in the studio, which I've been collecting since 2003. I kept things that I didn’t use, so I have archival elements. I started with these elements and then introduced new ones like leaves and candy wrappers, or graphic papers. Until 2011, I had a collection of candy and chocolate wrappers, which I incorporated in my collages for many years.

How do you know when a collage or painting is finished?

It’s difficult to figure out exactly when a work is finished. Sometimes I have work that stays with me a year. It’s not that I am working on it the whole year, but I don’t feel that it’s finished yet; I might keep it and look at it for one year.

My process is very slow—it’s not just the time spent reflecting on it, but also the time of the technique, which is laborious. The collage is a faster process because they’re paper cut-outs. You have limitations with paper and you can’t push it too far, whereas painting is very open, so you yourself are constantly creating and developing. With collages, you already have the limit of the cut out paper. That determines and helps you see when something is finished. Overall, I think it’s the colour combination that helps me determine when something is finished. In Turkish Garden (2014), I started with the background and then I put a trunk in the middle and then added magenta leaves. I then decided it would be a magenta tree and I filled the surface with the magenta leaves.

There are so many different reference points in your work—smatterings of Matisse, abstractism, Op Art—but the style is also uniquely yours.

Yes, I have a strong connection with the Brazilian modernism of the thirties, especially Tarsila do Amaral, and then Matisse, and later Mondrian. It was a triangle of influences from the beginning; they were my company going into the studio.

More recently, I started using some abstract symbols. I never copy or make drawings looking at something, because it’s never worked for me when I’ve tried this. I always prefer to work with imagination, or I have a more spontaneous relationship with the object of interest.

Exhibition view: Beatriz Milhazes, White Cube, Hong Kong (13 March–30 May 2015). Courtesy White Cube. Photo: Vincent Tsang.

Is there a formula behind your use of colour?

Not really a logical one. I think of myself as an abstract geometric artist. My use of colour has changed. For many years, my work had a more melancholic tone—there was memory and time behind the colours. And then more recently it started to get brighter and brighter. Yellow, for example, has a strong presence that wasn’t really common in my early 2000s work. I wouldn’t say it's just intuitive, but there’s no formula. I would like to have one, but it's very complicated working with colours. I’ve been working with colour for 30 years, but there’s always something new, even when you think you know it all. Pink might work in one painting but destroy another, for example. Colour is something you can never learn enough about, and that is the fascination of working with it—that you’re always learning more things about it.

Flowers always interested me, but that came from an interest in the applied arts, not necessarily from looking at nature. Decorative art is something that I’m really interested in. I like this human touch and human expression that is very intimate. It’s not something that we require, but we need it for our wellbeing; for the soul.

Gallerist James Cohan has described the imagery in your work as 'defiant feminism', and your work is often positioned in terms of your gender, in the context of you being a female artist. How do you feel about being positioned first and foremost as a female artist and your work being seen as feminist simply because of your gender?

I never really thought of my gender as a theme or inspiration in my work, or even in a political context. But I can see how some elements in my work are very female, or belong to the female world, like my interest in handmade costumes and fashion. They are seen as coming from a female world, and I do use them as motivation in my work. The fact is that the world of painting is very male. In South America, to become an international artist is a political statement in itself. I’m a woman! Of course the way I look at things is probably a woman’s way of looking at things. It’s okay if that’s how they position me. What needs to happen is for people to see that women are also intelligent and can introduce and contribute things to art, and that we can drive things forward in terms of meaning. Connecting my work with gender is very obvious, but it’s not the rationality that drives it.

Have you come across challenges being a female artist?

In Brazil, our art history has respected many female artists. I grew up in an environment, where painting wasn’t an exclusively male activity. When I started in New York in the early nineties, however, I suddenly noticed that things were different. I started to understand why feminism developed and started in the U.S., because it’s a real thing! Painting was male work, and women were put in a different box. It was a fight to get out of that box. To me this was surprising; I wasn’t expecting it. I felt like I needed to prove that I was serious when I entered the international field. I feel that this still hasn’t changed. The number of women who get to the top are few, and the prices are also very different between works by male and female artists. It’s unbelievable if you think about it.

You’ve claimed a space for yourself in the international art market using techniques and influences borrowed from decorative and craft arts, which have traditionally been disparaged in the art market and perceived as low-brow. You’ve repositioned these techniques as high art.

Yeah, this is an interesting point.Robert Storr once visited me in the studio and said exactly this: 'As a woman you pretend to be a painter, using all pejorative, low culture elements, and now you’re on the cover of ArtNow.' Yes, I’m shifting low art into high art.

Exhibition view: Beatriz Milhazes, White Cube, Hong Kong (13 March–30 May 2015). Courtesy White Cube. Photo: Vincent Tsang.

Your work has shifted recently from floral compositions to more abstract geometric ones.

I think the geometry was always there. I always felt like a geometric artist, but now the abstraction has become clearer and has become the point of observation, that’s true. It’s evolved in this direction.

A few of the works, like Cake Landscape (2014), have an almost Bridget Riley feel to them. The lines seem to throb and move. Or is that just my hangover?

[Laughs] Yes, the circle became the most important geometric shape I use. It’s disturbing. There’s no centre and it makes your eyes move. Bridget Riley was always an influence, but now I look at her optical works as references in the paintings; before it was the concept of the optical, but now it’s physically there.

Are you working on any other projects at the moment that you can tell us about?

I’ve been doing different museum shows. In January 2015, I closed my first U.S. museum show. I then had a show in New York at James Cohan Gallery, followed by a project with the Jewish Museum in New York, too. They will have a retrospective of Roberto Burle Marx, a Brazilian landscape architect, drawer, and painter. The Jewish Museum is developing a retrospective of his work and they wanted me to do a piece for the entrance. Burle Max was always a reference for my work. —[O]