Billie Zangewa: Soldier of Love

Billie Zangewa. Photo: Carole Desbois.

Billie Zangewa. Photo: Carole Desbois.

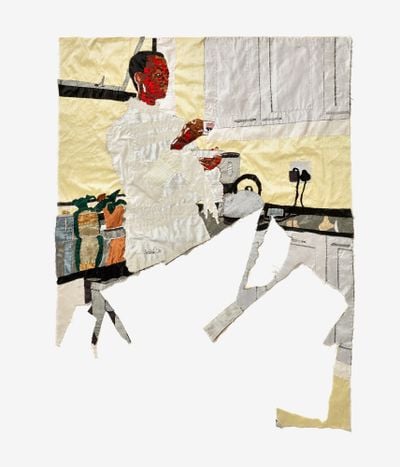

Johannesburg-based artist Billie Zangewa creates intimate portraits and everyday scenes from collages of dupion silk swatches meticulously hand-stitched and embroidered by the artist.

Zangewa was born in Malawi and grew up in Gaborone, Botswana, before moving to South Africa to study fine arts at Rhodes University. Initially focusing on printmaking, Zangewa later gravitated to working with raw silk cut-offs. The material's characteristic as a by-product of a silkworm's transformation also serves as a metaphor for the transformative processes involved in creating works of art—a metaphor that emphasises Zangewa's practice as existing beyond the frame of categorisation.

Blurring the boundaries of photography, textiles, and portraiture, works like Ma Vie en Rose (2015), which shows Zangewa standing in her kitchen holding her baby, appear like intricate and ornate snapshots of personal, social, and cultural experiences that encapsulate themes of domesticity, femininity, and solidarity. In Christmas at the Ritz (2006), a luscious, raw silk painting of the artist in bed is composed of golden panels and detailed stitching that build a patchwork of references surrounding the central scene of the artist lying in bed: the logo for the Ritz, for instance, and high-fashion label Issey Miyake, which gestures to the artist's background as a model.

Zangewa's practice of hand-stitching began early on, with the artist learning to sew from her mother, who was a needle worker, and often convened with other women as part of a sewing group in their different homes. The group, a young Zangewa observed, not only created useful and pretty items for their homes, but also supported each other by conversing and sharing space while carrying out their repetitive stitch work.

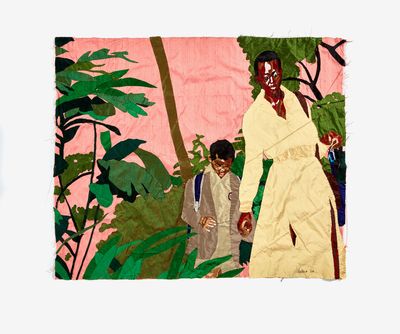

The idea of sharing space feeds into Soldier of Love (14 March–6 June 2020), Zangewa's first solo exhibition at Templon in Paris, which explores the universality and timelessness of love. In works such as Soldier of Love (2020), from which the show takes its title, the artist is pictured walking with her son to or from school amidst a lush green landscape. Conversely, The Swimming Lesson (2020) depicts the artist's young son standing apprehensively at the edge of the swimming pool, seemingly pondering whether or not to go in: a portrait of a child confronted with a new challenge.

In this conversation, Zangewa discusses sewing from an early age, turning the mundane into the relatable, moving beyond domesticity as a central theme, and celebrating femininity in a practice that expands personal histories outwards through textiles.

JDFemininity, domesticity, and solidarity are prominent themes in your practice. Do you see your works as a reconciliation between feminism and domesticity?

BZNo, I don't necessarily see my works as a reconciliation as you mention; I rather see them as a way to turn the attention and focus on the unsung heroine operating within the domestic front. Women everyday are doing things to keep households going, as well as raising and nurturing children. This goes unrecognised. Domestic labour is taken for granted and not even thought about, even though it is what keeps societies going. The other concern I have is to give a voice to the lives of black women, as I still feel that we are marginalised. Through this sharing of her everyday intimate life, perhaps someone will finally see and hear her.

My politics are more in the personal acts performed in my work; the personal as political.

JDThe act of women coming together to work in domestic spaces—cooking together, sewing, rearing children, and so on—is intrinsic to communal life, particularly on the continent. How did these forms of commoning make an impression on you growing up?

BZYes, these instances of women coming together was definitely something that greatly influenced my growing up. Seeing my mother and her sewing group coming together to sew was a powerful experience for me, but it was really the impact that the act of sewing had on the mood of these women that I bore witness to that was remarkable. Even as a child, I was able to understand the soft power and subversiveness of sewing, and that there is a reason why women have been doing it for generations.

JDThere's also the reality of these spaces functioning as 'safe spaces' for black women. A place for sharing but also for caring for one another.

BZSupport systems are very important and really help people to cope with challenges. I work alone and love the solitude, but I have two wonderful ladies who support me when I need it and it's great to have that. It's a symbiotic relationship where they help me, and I too help them by providing employment. I think it's important to support each other not only through difficulties but also successes.

JDWhat does the act of stitching represent to you?

BZSewing for me represents self-empowerment. It's a way for me to express myself; to use my voice, and express my identity as a woman. It's also a form of therapy. The repetition of the needle going in an out and then pulling the thread through is very soothing, almost hypnotic. It's also a form of meditation, as it requires so much focus that there is no space for negative thoughts. The final outcome is also very affirming because it provides evidence of an endeavour.

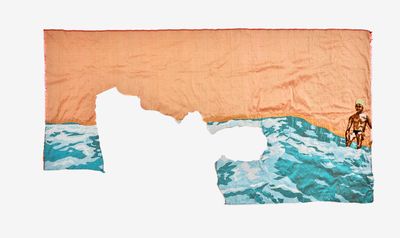

JDIn past works such as Christmas at the Ritz (2006), and recent works like The Swimming Lesson (2020), textiles incorporates irregularities, like cuts and incisions or uneven pieces. Is this a conscious way of working, or is it a response to the nature of the silk cut-offs themselves?

BZIt's always organic. When I first used an irregular piece it was by accident, and I still allow the process to dictate. I don't make the irregularities deliberately, as different works inform each other, so they are in fact in conversation. When it first happened, I realised that it was a great way to bring the viewer back to the medium of textile. Most people think my works are paintings when they first experience them. I liked the idea that the missing bits represent some kind of external force, like time and wear and tear having some kind of impact on the fabric. On another level, I see it as the perfect representation of the imperfect aspects of the self, while representing an internal wound that is to some degree present in all of us.

JDIn the press release for your current exhibition, Solider of Love, you state: 'universal and personal love is something that we have to fight for. I consider myself a soldier of love.' Can you expand on this?

BZI feel that at present, we live in a time blighted by a lot of violence and transgression in different forms that we inflict on one other as a society. We hear about it on the news every day. I believe that it is because we do not prioritise love, and that if we did, most of the suffering in the world would come to an end and we would find healing. Unfortunately, love as the answer is seen as an idealist dream, so to convince people of it is not an easy task; hence the war for love. I am a soldier of love.

JDThat capacity to communicate love in the universal realm somewhat speaks to the idea of the individual genius in art. What are your thoughts on this?

BZI think it's great to be acknowledged for one's accomplishments, but I also think being a creative is a lot more complicated than people imagine. I believe that each person has their own journey and hopefully it ends in love. I hold only myself responsible for what I do and feel, not anyone else, as I do not know their individual journey and path.

JDCityscapes were a subject you explored before you started working on domestic and personal scenes. How did a process of self-examination and self-love shape the works currently on view in Soldier of Love?

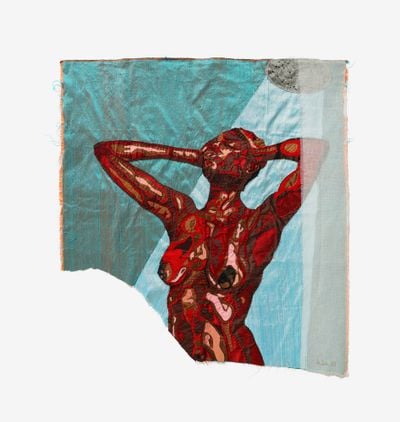

BZLove is the overriding theme in my exhibition. When exploring it, I realised that to give love—to be a loving person—begins with the self, and that we have to love ourselves before we are able to love anyone else. In works such as Sunday Morning Pursuits (2020) and At the End of the Day (2020), I am taking care of myself and making sure that I can replenish my energy as a form of self-love. The nude Am I Enough? (2020) is speaking to the challenges of self-love in the face of self-loathing—it confronts how we speak to ourselves when we face ourselves in a mirror.

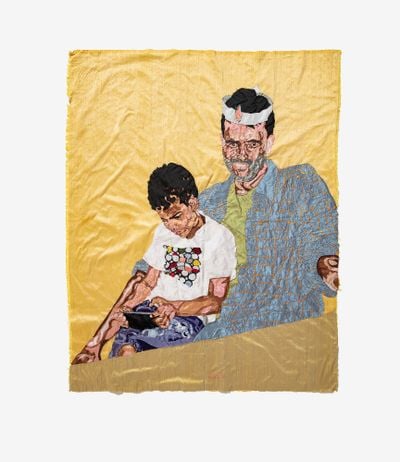

Birthday Party (2020) and Soldier of Love (2020) speak to the giving of love to another, in this case my son, and how love shapes a child. The variation of ethnicities in Birthday Party speak to universal love and my wish that we could look beyond skin tone to experience true universal love. Cold Shower (2019) is about the challenges of romantic love, especially when love was modelled badly as a child. It also says that no matter my challenges in this department, I'm not giving up on myself or love, because I am a soldier of love.

JDCould you discuss the myriad skin tones you create in self-portraits such as Sunday Morning Pursuits (2020), and how this complicates or provides a new grammar for blackness?

BZI have always portrayed the way light plays on skin rather than the skin tone itself. African skin comes in so many different tones, and depending on the light saturation, the same tone can change. This is true of all skin tones. I enjoy colour. My politics are more in the personal acts performed in my work; the personal as political. Any variation in skin tone is about the mood of the piece and the light. I couldn't imagine portraying skin in the same tone over and over again.

I definitely think that mothers can be artists and women do not need to choose one or the other. This is an antiquated idea.

JDThere are so many myths out there on black lives in relation to depictions and who is depicting. How do you counter this in your works?

BZI let the viewer into my personal life by giving visual anecdotes of things happening predominantly on the home front. I come from the perspective of the personal as political to show that we are all connected; that we all have the same daily concerns no matter our skin tone or where we are in the world. By showing the daily life of a black woman I'm saying, 'Look, I'm just like you, we are the same, we are connected.' I believe that if you can relate to someone and connect with them, you cannot hurt them, because it would be like hurting yourself. A big problem in our society is othering, which really stems from fear, and people don't make good decisions coming from such a place.

JDDo women really need to choose between motherhood and art? Can mothers be artists? This still seems a debatable issue. Did you face any challenges or pushbacks in exploring this important relationship in your works?

BZI definitely think that mothers can be artists and women do not need to choose one or the other. This is an antiquated idea. There are also different types of mothers—some delegate the care of their children to someone else so that they are free to work, and others like to be hands-on parents, which makes things a little more challenging for their work. My works trace my personal growth, so inevitably, when I became a mother I wanted to share this experience and sit became the subject of my work. Initially, when I discussed this with my gallery at the time, they didn't support my idea, but I'm a very stubborn person and I took the risk and did it anyway. To my surprise, the response was positive.

One of the challenges for hands-on mothers is that time for work is limited, affecting production potential. This can be difficult when working for a solo show, but I find that I make the most of work time when I get to it and the limitations have given me a deeper appreciation for it.

JDCould you speak of other themes you seek to explore in future work?

BZI have no idea of the future and what it holds. I am of the opinion that it will reveal itself to me when it wishes, and I am ready to receive this when it happens. I really don't plan far ahead; I'd rather surrender to life and what it has in store for me. My work will, however, continue exploring the self, its multiplicities, and evolutions, and I'll continue sharing these experiences with others. Personal growth is a lifelong journey. —[O]