Cecilia Vicuña: The Colour of Compassion

In Partnership with CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts

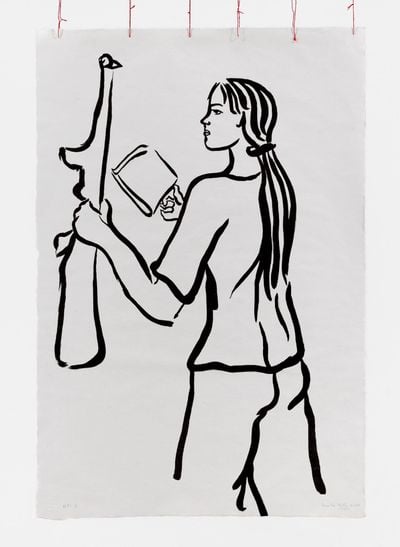

Courtesy the artist. Photo: Jason Schmidt.

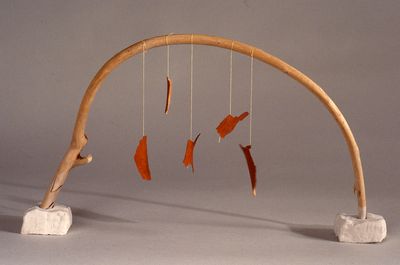

Courtesy the artist. Photo: Jason Schmidt.

Between 28 September 2020 and 1 August 2021, the CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts in San Francisco is programming a series of events informed and inspired by themes in the work of Chilean contemporary artist, Cecilia Vicuña.

Born in Santiago in 1948, Vicuña left Chile in 1973 for London, having received her MFA from the University of Chile in 1971. Attending the Slade School of Fine Art, after being awarded the British Council Award in 1972, she was in London during General Augusto Pinochet's 1973 coup, forcing her into exile in the United Kingdom.

Spending time in Colombia and Brazil researching indigenous culture in the latter part of the 1970s, Vicuña relocated to New York in 1980, where she is now based.

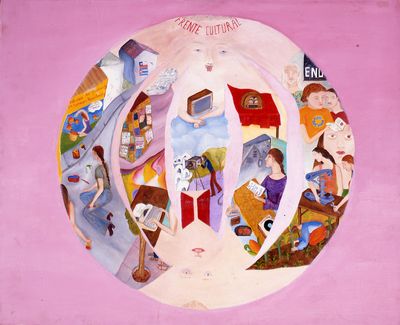

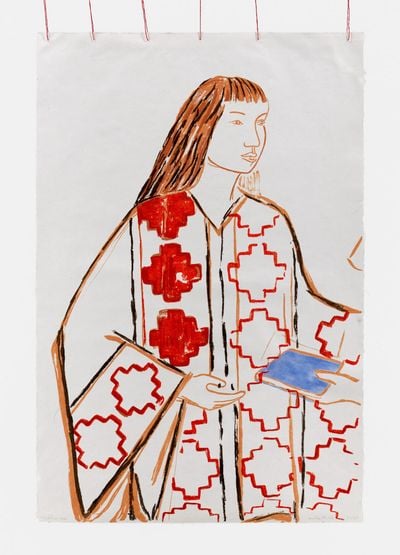

For more than four decades, her practice has encompassed political activism, street actions, films, painting, sculpture, poetry, and performance, using feminist and sociological methods and indigenous culture and materials to resist capitalism and disrupt colonialism. Pre-Columbian systems, such as quipus—a method of record-keeping that involved knots tied into strings that were created and read by specialists, known as khipucamayocs—are given sustained attention in her practice.

The method, which was banned during Spanish colonisation of the Inca Empire, features in the artist's installation and performances, including the recent Lava Quipu (2020). In the video poem, filmed on the occasion of her solo exhibition at MUAC in Mexico City (Seehearing the Enlightened Failure, 8 February–2 August 2020), Vicuña memorialised the lives of femicide victims in Mexico, with participants dotted along a vast length of wool died a rich red. Raw and unprocessed, the fragile wool had to be handled with care. 'The only way it will stay together,' Vicuña narrates in the film, 'is to treat it with immense love.'

On 11 February 2021, the artist premiered the film along with two others—A Circle for Mapocho and El veroir empezó (both 2020)—to audiences online, speaking with poet and translator Daniel Borzutzky about her practice afterwards.

The event preceded the opening of Seehearing the Enlightened Failure's Madrid iteration at CA2M – Centro de Arte Dos de Mayo (20 February–11 July 2021) and Quipu Girok (Knot Record) at Lehmann Maupin in Seoul (18 February–24 April 2021), which runs in parallel to the 13th Gwangju Biennale (1 April–9 May 2021), where her installation Rain Dreamed by Sound (2020) is being shown. Forthcoming exhibitions include the 13th Shanghai Biennale (10 April–27 June 2021), for which Vicuña will present a series of new paintings based on her lost works of 1969, and a solo exhibition in the rotunda at the Guggenheim Museum in New York in the summer of 2022.

The following is an edited transcript of Borzutzky and Vicuña's conversation.

DBThe film El veroir empezó, performed at the Centro Cultural Gabriela Mistral in Santiago, recreates a performance that you did in 1976. In the performance, you wear a pair of glasses, titled Truth / Give Sight (1974), which are part of the 'Palabrarma' series—a poetic system in which words open up to reveal their inner metaphors, converting them into tools for liberation.

Could you talk about why you chose to bring back this idea from 1976, and the connection between 1976—just a few years after the dictatorship began in Chile—and the art you are making in the present moment?

CVTruth / Give Sight is completely connected to the military coup. I was in London on 11 September 1973, with a grant to study art in London, and I had about two more months in London before my return to Chile, when the coup happened.

People who are too young to have been alive back then, they won't know—and a lot of people don't really know this—that the military coup was justified by a very powerful fake news. It was a lie, most likely composed by the CIA, claiming that the military coup was a preventive measure because the democratically elected government of Allende had a secret plan to murder thousands of people and kidnap children to indoctrinate them into the idea of communism, by taking them to the Soviet Union. In other words, a horror story, very much like the horror stories we're living now in the U.S.

The current campaigns of misinformation are created through very powerful technological means that were not available in 1973 when the coup happened. But, when the military coup took place, it immediately took hold of the airwaves and the lie was dispersed. The lie became the death and disappearance of thousands of people and the destruction of the democratically created culture of Chile.

Shortly after the military coup, I suddenly saw what the word 'verdad', or 'truth', was really doing. The composition of this word is 'ver', which is 'to see', and 'dar', 'to give', so truth is not a given, but something that is created in the process of giving. I was so blown away by that image that I created that work. That was in 1974.

...by remembering the things that nobody wants us to remember, like the ancient way of living, for example, it gives us the possibility to remember a potential.

It was in 1976 when I converted that image into a set of cut-out paper glasses and I began performing with those in the street. Of course, nobody paid any attention to me because it was in Bogotá in the seventies. And so, when this horrendous campaign of misinformation began to distort the Estallido Social, the social uprising in Chile in 2019, I immediately saw the parallel. Plus, by the time that this was happening in 2019, this campaign of misinformation had achieved getting governments in places like Brazil and Italy.

The performance references the action of police, which I believe was created in Israel, where people are shot at in the eyes. It was implemented in Chile with an effectiveness never known in any other country. Children as young as 12 have lost their eyes. So it's a violence against the ability to see; to see the difference between a lie and truth.

DBMoving from the dictatorship and 1976, to the social movement of 2019—this latest movement has led to the upcoming referendum that will result in a new constitution being written. So in many ways, we can call the movement a success.

I was struck by something a friend of mine said in talking about its successes. I had asked him why he thought it was successful this time, and he said it had to do with the aesthetic that the protesters created that allowed them to unify, especially the young people of the movement, and that previous social movements were using the iconography of the 1970s—of the Communist Party and of Salvador Allende—and that in Chile in 2019, the references were to things like the #MeToo movement, K-pop, and things that were much less known to the old guard.

This coincides with something you have told me, which is that your work is being accepted and absorbed in Chile now in a way that it wasn't in the past. Do you want to begin by speaking to that idea of the aesthetic that was created in the social movement of 2019? How does your work belong within that aesthetic?

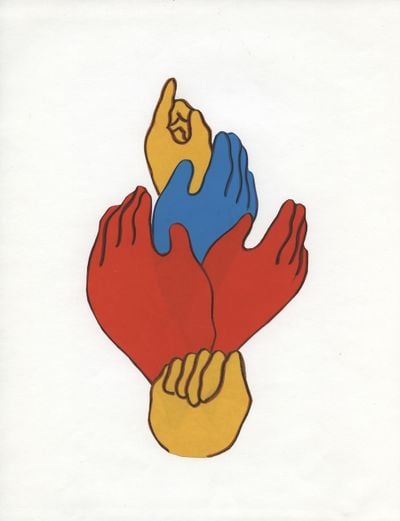

CVYeah, I think it's a fantastic question, because the idea that an aesthetic has a political power, and an ethical power, as well—an ethical, poetical, political dimension to it—is something that is very ingrained, I think, in a portion of very radical poetry around the world, not only in Chile but also in the indigenous uprising and in the feminist uprising.

It's pretty clear that this uprising of the feminist movement, which is perhaps the driving force of movements around the world, and the indigenous movement, is something that the young people are responding to now in a way that was never possible before. The only time when I have felt what you feel now in Chile, and I began feeling it around 2011 with the big student protests, was the sixties.

That is what made the sixties what they were—that suddenly, an ideology was no longer the ruling force. It was just a desire; a desire to be. To be together. And in the sixties and seventies, that desire was squarely associated to the desire for justice; the demanding of justice. So that is what has been reborn—the desire to be ourselves, which creates, of course, an aesthetic of the moment.

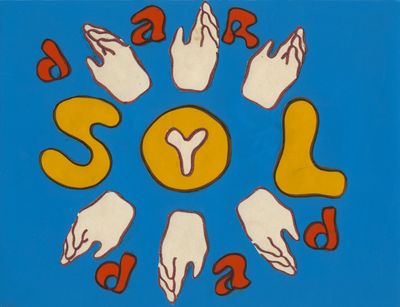

This was fantastic to see in Chile. Poetry is something that has been marginalised by Western capitalist society everywhere in the world. And in this uprising in Chile, the first thing that was seen everywhere was people writing poems on the walls, not only Santiago, not only in the neighbourhood of the intellectuals—let's say the Barrio Bellavista or downtown Santiago—but in every town of Chile.

I travelled to a talk and found philosophical expressions on all of the little houses. To see that is like this suppressed poetic vision was emerging through the pores of society.

DBThinking about the last film, Lava Quipu (2020), it occurred to me that there might be some people who are not familiar with the history and importance of the quipu, and so it might be useful for you to speak about that a bit.

Each of the films fuses collectivity with the natural environment and an idea of integration and return to the natural environment. In the performance, at one point, you say, 'We're going to return to being plants now.' It would be nice to hear you talk about how you were bringing people together to interweave collectivity and the environment as a means of speaking about the social present.

The other thing that struck me was that the environment was being used in your performances as a way of speaking about privatisation and contemporary military violence. The quipu is of course the strand that runs through all of it.

CVQuipu is a Quechua word that means 'knot'. Quechua is an indigenous language of the Andes spoken perhaps by a few million people. But it's one of the large languages.

The idea of the knot is very interesting, because in terms of mathematical constructs or structures, the knot is the most complex mathematical object that exists. It involves multi dimensions and it's practically impossible to calculate what is in a knot. The ancient people of what is now called Peru created quipu as a method of keeping records. It was like a non-writing writing system that was in use for 5,000 years.

It reached a level of complexity where there were whole libraries of quipus, and quipu messages were sent back and forth all over the Inca Empire that existed all the way to the north in Ecuador, and south, to the central part of Chile and north of Argentina.

So it was this huge universe that was united, not only by the tactile quipu records, not only of statistics, tributes, tax, and things like that, but also of history and poetry and music.

So when the Spaniards arrived during the conquest, they looked at these threads with knots and they paid zero attention to them, but almost 100 years into the colony, when the Spaniards started to grab hold of the land of the people, the people began showing up in court with their quipus in hand, to counter the written law of the Spaniards with the testimonies that were inscribed in the threads.

When that happened, quipu were abolished, destroyed, eliminated. The khipucamayocs—wise people who knew how to tie information into the knots—were killed, so the quipu disappeared.

For more than 400 years, everybody forgot about quipu. And then in the sixties, two artists who did not know each other began working with quipu—in Peru, Jorge Eduardo Eielson, and myself, in Chile. I was a teenager, and he was an older artist and poet. He gave it up after a while, but I carried on.

DBI didn't know that you and Eielson were doing that at the same time, with the quipu. There's a translation of Eielson's that came out last year for those who are interested.

Okay, so we're getting questions from the audience. One question asks about how you feel in your body when you're singing? What areas of your body is your voice coming from?

And then there is another question about breath. This is from Edgar Garcia, and the other is from Indira. Edgar is asking about breath and breathing, which he talks about as being so important to your performances and ceremonies. The acts of breathing and the playing of the flutes include singing, respiration, whistling, hissing. Just in watching them, he says it was so striking, because today, acts of breath are hidden by the masks that we wear. He wonders what you have to say about breath in this time of universal mask-wearing, breath protection, and face-hiding?

So, on the one hand, we have a question about breath, and related to that is a question about voice.

CVIt's a wonderful question, thank you, Edgar. It is true that we live or die according to our breath. So the fact that breath is now the colour of death, the colour of compassion is the most dramatic thing that has happened to humanity, I think, in a very long time.

It is truly the threat of extinction; the collective extinction of the human race, that I think we are facing. This possibility is not a done deal, but going out in the street and seeing human beings and knowing that they may be a carrier of your potential death is something that only people in the most devastating wars have experienced. But now we all are experiencing that. So, breath is a life-giving force that has been converted into a death-giving force. It just comes down to that.

Now, in terms of how I work with the breath—I once got very ill, and the doctor felt my pulse, and said, 'I don't know how you're alive, because your pulse and your breath is almost as if you were not.' He asked what I was doing, and I said, 'Well, I was writing poetry.'

I became aware that when I write poetry, and when I do performance, I go into a mode of breathing that is sort of like—Ray Charles had a wonderful word for that, he called it the 'death tempo', which is very slow and quiet, so quiet that your heart is sort of sub-beating. It is the function of deep concentration.

Art and poetry are opening us to admit all the aspects of ourselves that we're not supposed to consider as powerful or important, because they are, essentially, subversive to the system.

All of us can do that naturally if we're deeply concentrated. And I suppose, in order to do these performances, I have to abandon thought, as what happens during meditation. If I start thinking, performance is no longer possible. You have to dissolve and disappear in order to do the performance, and the way to achieve that is through breath—breath that breathes on its own accord, without interfering thought.

Now, about the question as to what part of my being, my body, the sound comes from. My answer is very weird. You have forced me to think a thought that I don't like to think, because it makes me say something that I don't want to say, which is that the sound doesn't come from me, it arrives.

Where is the landing place of that arrival? I don't know. But it's somewhere very deep that I had supposedly suppressed throughout my life, until I was an older girl of maybe 35, 40 years old. And suddenly I couldn't suppress it anymore, and this came out, but the feeling of it having entered and then come out was very clear. It gives me chills to say that.

DBI'm struck by your statement that you have to dissolve and disappear for the performance to appear, which makes me think of what the collective is doing. The collective is actually appearing almost as the creators of the work, and I think that that becomes especially clear in the video at the river, as well as the film at the Centro Gabriela Mistral.

We have a question from Chela—she asks, 'What role does art have in preserving memory and in sustaining resistance?'

CVWell, art has everything to do with memory. But not necessarily memory of the past. Memory is a very complex thing. Actually, we know very little about how memory works, except that it's already acknowledged that memories create fact.

What we think we're remembering, we're at least partly creating as we remember. And that is a very beautiful thing, because by remembering the things that nobody wants us to remember, like the ancient way of living, for example, it gives us the possibility to remember a potential. A potential of who we really are as human beings.

I think the most horrendous thing that capitalism and Western societies have created is not only the destruction of the environment, but most of all, the destruction of who we are—it is a sort of reduction of what we can sense, feel, think, and do. And so the notion of the collective is precisely because, if we're going to survive as a species, we have to come together in the decision to live, as opposed to die.

What role does art play in that resistance? It is against the reduction of who we are. Art and poetry are opening us to admit all the aspects of ourselves that we're not supposed to consider as powerful or important, because they are, essentially, subversive to the system. Humanness, kindness, passion, and loving are subversive acts in the society of cruelty and selfishness and greed that we live in.

It sounds really stupid what I say, but I think stupidity is in our favour right now, because so many forms of 'ruled' stupidity are diminishing us, so we can use the stupidity to release us, to deliver our most fundamental sense of what is ethical in this moment, and it is to work, all of us, together. Even as I say it, my hair stands on end, because it seems the hardest thing right now.

DBThere's another question about the importance of film-making in your overall practice, and I recall our discussion when we screened films in Harvard a few years ago, where you said, 'Oh, I don't know anything about filmmaking.' And then, in the next line, we learned that you have made hundreds of films over the last however many decades.

She's asking about whether you could talk about that, and specifically mentions that you are not, in these films at least, the one holding the camera.

CVIt is absolutely true that I know nothing about cinema. I never studied it and I was not supposed to be a filmmaker at all. Suddenly I found myself doing films, and suddenly I found that I had done hundreds of films. How is this possible? I think it's possible because I acknowledged that I know nothing. And because I know that I know nothing, I can explore, and I can do weird stuff.

Also, all my films are created through association. In other words, I find these wonderful artists who are willing to work with a non-director director—you know, someone who knows very well what is going to be the dream, but knows absolutely nothing as to how it's going to happen.

It requires a fantastic collaborator—someone who would be at ease with my method of acting that is without preconception. It all just happens, so I have created terrible disasters of some of my films. And some, even though they may have lots of defects that would technically ruin them, there's something in them that is alive.

I attribute it to the fact that I go into it like I do my poetry: with nakedness, not imagining or pretending that I am this or that. I am nothing. And nothingness is truly the best condition that we as humans have. We can be poems, plants, animals, rocks... we can be anything. —[O]