Ellen Altfest

Ellen Altfest. Courtesy the artist.

Ellen Altfest. Courtesy the artist.

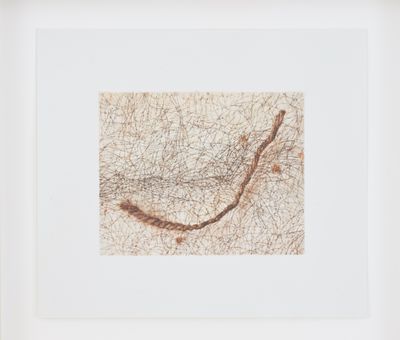

The paintings of Ellen Altfest are ethereal in their detail. Fields of minutiae come together as pulsating images; small brushstrokes of oil paint accumulate over a series of months to single out seemingly innocuous subjects, such as a hand resting atop patterned fabric (The Hand, 2011) or a deep green cactus reaching upwards from beneath a bed of pine needles (Small Cactus, 2004).

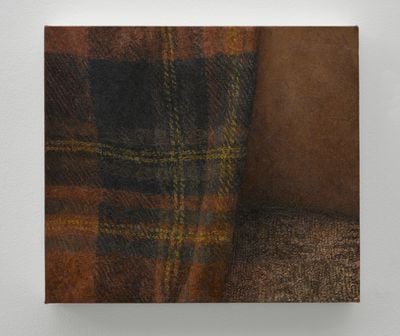

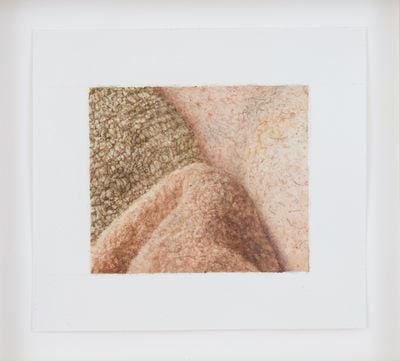

Altfest spends time with her subjects, concentrating on a corner, section, or frame to render it alive with paint. Since the mid-2000s, she has sat with male bodies, bringing them into her canvases as still life objects. In The Penis (2006), the male member is framed between thighs, which sit atop a stool, every hair, wrinkle, and crevice laid bare. 'As a woman, I had complicated feelings and was thinking a lot about men, and I wanted to understand them better', explains the artist, whose inclusion of the male form in her small, tightly composed canvases has shifted to virtually imperceptible inclusions in recent years. In Composition (2014–15), for instance, a patch of bare skin brushes beneath a brown, black, and yellow plaid blanket, the texture of the sofa perceptible in the bottom-right corner, fading into darkness beneath body and blanket.

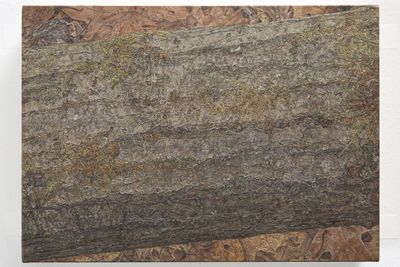

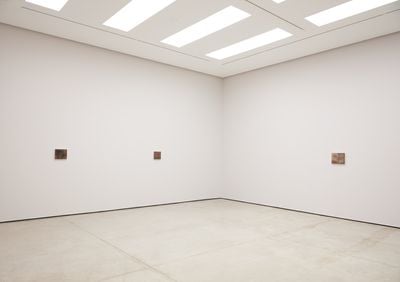

After receiving an MFA from Yale University in 1997, Altfest attended the nine-week residency programme at Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine in 2002, with her first solo exhibition taking place at Bellwether in New York that same year. Titled Rocks and Trees, the show revealed deft, textural representations of tree bark and lichen-covered rocks. Her naturalistic representations are frequently painted on site, as in the case of Tree (2013), for which Altfest spent 13 months revisiting the same fallen tree in the woodlands of Connecticut, to paint a section of its trunk hovering above the leaf-strewn ground. The work, which was first shown at the 2013 Venice Biennale, is now on view at White Cube in Hong Kong, where the artist is holding her first solo exhibition in Asia (Green Spot, 11 January–16 March 2019).

On the occasion of the exhibition's opening, Altfest spoke with Ocula contributor Sherman Sam about her practice. The following is a transcription of the talk that took place at the gallery.

SSOne of the reasons I really love your work is that you are the only painter I know personally who is slower than me. Last year I made four paintings; that is still more than you. I feel comforted when I'm around slow painters. How do you make paintings such as Tree (2013), which you painted en plein air in the woodlands of Connecticut over 13 months? How do you start?

EAWell, in that instance I went around the woods. There are two ways I work: I either find a composition on site or bring things I find into the studio. Walking around the woods is almost like shopping—I have a general idea of what I'm looking for, but I also respond to what I see. I look at all the natural objects as possible candidates for what I'd like to make.

I take pictures as I walk around. I don't paint from photographs, but the pictures help me remember the different things I've seen. I put neon plastic hunter's tape in trees so I can find my way back to the subjects I'm considering. I do shorter drawings of two or three of the subjects, and, after I've chosen one, I figure out the composition and work out the exact dimensions with longer drawings. Then I transfer the drawing to the canvas. Even at that point I might realise that it doesn't look right and then need to order a stretcher with the new size. I'm going to be working on the painting for a long time, so I want to get it right.

SSAt that point, when you make that decision between walking in the woods and finally deciding on the composition, how much time has passed? A year?

EAA year would be a long time to plan a painting! Let me just say that questions about time stress me out. I am usually in denial about how long the paintings take; I block it out. At first I think, this doesn't look so hard ... which is good in a way because it gets me going, but once I start painting I can see the amount of work that lies ahead. I am generally hit with a combination of aversion and stress. That said, I think that it takes me probably two to four weeks before I order the canvas. My paintings are these weird sizes like eleven inches and five-sixteenths. I like the edge that touches the canvas to be sharp and defined and the stretcher to have a certain depth, so it has a presence but doesn't become too much of an object. I have them custom made, which takes two to three weeks.

SSSo, then you decide on the subject of your painting and its shape and size. As you look at the white canvas, can you see the painting? I'm asking these really stupid questions because I'm actually an abstract painter so I can never see what I make.

EANo, you can't see what you make. I mean that would be really boring. First of all I forget and I might take those pictures of potential subjects to my friend Chie and to my husband Rob, to present the three top contenders for the painting, and ask what they think. I'm not above a little referendum.

I don't think I know exactly. Sometimes I think it's like a leap of faith. I might recognise something that I like about the composition, but I don't exactly know what it is, and I don't know what it's going to look like in the end.

SSIn the case of Tree, you saw this piece of wood? A trunk?

EAYes, a fallen tree that is so big it is hovering off the ground.

SSAnd you drew it, and you got the canvas ordered, and then? And then Rob decided that was the right one?

EAThe show took so long in the making that I didn't even know my husband at that time ... he wasn't even a twinkle in my eye. I was completely alone out there. Chie might have seen a picture of the tree and said it looked good. I had painted a leg in Marfa that was like an abstract shape dividing the painting. I wanted to make nature sort of equivalent to what I was doing with the human form. The tree is like a thick mark moving across the painting, and by making it touch the edges it became flatter and more compressed. So that is how I composed it, and that was what I saw. I mean I see the tree and then I see the canvas. But, as I'm working on it, even early on, the canvas does become the tree.

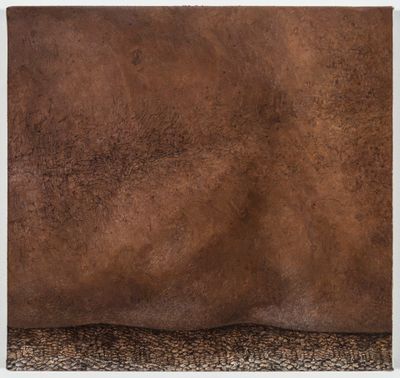

SSAre you drifting away from painting parts of men's bodies and focusing more on surfaces? The first floor of the exhibition at White Cube is mostly surfaces.

EAYes, this show has been, in part, about phasing the men out or demoting them. Men were central for a long time and now they're compositional elements and have been pushed into the background. It's a goodbye to the way that it was, but also a different approach. So what you say may be true but I wouldn't hold myself to it. For my next show, I can imagine having, say, eight paintings and one of them has a man somewhere in it. I feel like as an artist you have a vocabulary of what you paint, or at least I do, and the male body is part of my vocabulary. I reserve my right to bring it back in different ways as it occurs to me.

SSWhen did you first start painting men, and why?

EAI had a lot of different reasons. As a woman, I had complicated feelings and was thinking a lot men, and I wanted to understand them better. But it was also an inclination, not an idea. Right now I feel really drawn to working with plants and nature. It's not always this rational thing, it was more like I couldn't stop myself from doing it.

SSWhy did you choose to work from the world?

EASometimes these things are less of a choice and more of a given. I feel like I've always been on this path. I had training from a young age, much younger than most people. I think painting from observation is like learning a language, and it's much harder to pick up a new language when you're older. I happened to go to a school with an art department that started us drawing from plaster casts when we were 14 and then we moved on to intense life drawing classes. I got into the zone when I was drawing the figure. I had all these tools and wanted to build on what I learned. I knew I didn't want to be an academic painter but I wanted to develop a connection to contemporary art. So even though my work has changed a lot, it also feels like a continuum.

SSWhat do you think makes your work contemporary? I think it's a question that painters should always ask themselves, in this time when everyone can make anything out of anything.

EAI have been asked that. When people come to the studio and ask veiled questions about my favourite painters, they're looking at me to answer that question. I do like the fact that you can be the type of painter or artist who is at the forefront of the new thing and you ride that ride. There are also a million artists who are following that person and doing derivative versions of that style. Or you could be the person who is not following what others are doing, and there's a power to that and I think that I've always been that person. But in terms of being contemporary, it is like having an awareness of what's going on and also what to stay away from. I am hardest on representational painting, especially realist painting. There are things that are problematic that put that work outside of a contemporary conversation. It's as much what you choose to exclude from your painting, a kind of restraint. There is a very small group of painters who have a certain connection to realism who are in the contemporary art world and there is a shared sense of a connection to abstraction. It's not about a pure love of storytelling and narrative and emotion and realism; there's a restraint and a lot of checks and balances going on. I don't think artists can say how their work is contemporary, but I can tell you what I'm drawn to and what I stay away from.

SSI'm compelled to look at your canvases because it feels as if your touch is so intense—it is as if you are trying to transform the object into the painting.

EAYes, but trying to replicate what I see would just be slavish copying, and there's something else I'm after. There is a compulsive side to my personality that wants to keep going and going and going, to include everything in front of me; but I also think that there is a quality that is my own, that made the way it's painted—the way I paint. That's something that needs to be there. If it's not there I find that it's not so much that it doesn't look like the thing, but that it doesn't look like my thing. I work on that at the same time as I'm working on painting what I see.

SSWhat is your thing?

EAThat's hard to pinpoint. I almost want to say that I want the painting to be pleasing, because when it works it just looks right to me. It's not like I'm trying to simply make an example of my work, or a replica of what's in front of me, but it's like the paint has to have a certain quality, some kind of controlled expressiveness. That is a very subjective judgement to make.

SSLastly, I'm going ask you the same question that you asked Sylvia Sleigh in an interview that is included in the book about your practice published by Occasional Papers, Ellen Altfest: Painting Close-Up (2015). Is there anything specific that people don't understand about your work?

EAI think people sometimes get so into how amazing it is that I've spent so long painting and how wonderful it is that the work is so detailed, that they might lose sight of the fact that there's subject matter, content, ideas, choices, and reasons why I've composed it this way or chosen that thing to paint. I don't feel misunderstood, and I don't think I'm necessarily the one to write the essay, but I'd like other aspects of my work to be expanded and discussed.—[O]