Entang Wiharso and Sally Smart

On the 30 November 2015, an e-conversation commenced between Entang Wiharso in Yogyakarta; Sally Smart in Yogyakarta and her studio in Melbourne, and Natalie King corresponding from her office at the University of Melbourne. Their triangulated exchange foregrounded the major two-person exhibition Conversation: Endless Acts in Human History

, showing at the National Gallery of Indonesia until 1 February 2016. They candidly discuss friendship, cross cultural dialogues, serendipity, bodies and borders. Synergies emerge between their respective preoccupation with deep social, cultural, emotional and geographical concerns. The conversation culminated on 13 December at 10pm.

Working together in Yogyakarta from Entang’s studio in Kalasan, can you discuss the idea of a studio as rehearsal space for work in progress?

Entang Wiharso: The description that resonates in my practice is the idea of the studio as a laboratory for work in progress, where I conduct experiments, make observations, analyze and collaborate. The function of my studio is also more than a workspace − it is an office, library and workshop. My studio is a flexible institution because it is personal and transformable; it can expand and contract to suit my projects and needs. I believe studios are soft institutions, and in Indonesia they play an important role in shaping the art scene. In my creative process I often use my studio like a laboratory, testing materials, making observations about my data, analyzing and experimenting to make well-developed conclusions that support my intentions. Rehearsals, when they happen, are more common when I am making installations or multi-media works and there are multiple elements that I test to check and ensure that everything is functioning correctly before the work is presented outside my studio.

Sally Smart: The studio space is always, for me, a place for experimentation, rehearsal, making and discussion. Currently, I am working from Black Goat Studios: an elevated building structure, a Jogja pavilion encased on three sides with glass, overlooking fields, nearby buildings and the gardens of Entang’s home and studio. This sets up interesting challenges as typically my studio practice engages with solid walls to pin and un-pin elements whereas this new environment has forced me to look at alternative ways to assemble my works within the architecture of this building. I wrapped fine white fabric around the inner columns of the space to work from both sides, and have responded to the shadows and the movement in the hanging elements – composing figures, and fragments of metal and fabric in a more abstracted way.

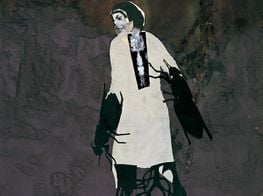

Image: Sally Smart, Global Garden, (detail), 2015. Synthetic polymer paint on canvas with collage elements, 300 x 540 cm (3 canvases, each 300 x 180cm).

I look out on this tropical, paradise Kalasan garden: the flowers, the scents, the foliage, the fish, the bird life and the insects. All the creatures in the garden and beyond resonate with the wonder of the natural world. I also look out to the neighbouring village with the daily choreography of farming. To the north, the majestic Mount Merapi, Gunung Merapi, is an active stratovolcano located on the border between Central Java and Yogyakarta, Indonesia; the most active volcano in Indonesia has erupted regularly since 1548. To the south, I can see the black grey stone of the beautiful Hindu Temple Prambanan. This is an environment resonant with compelling symbols of human culture and nature, compressed and complex, echoing across human history.

You both deploy performative figures in clustered arrangements. Can you discuss your mise en scene?

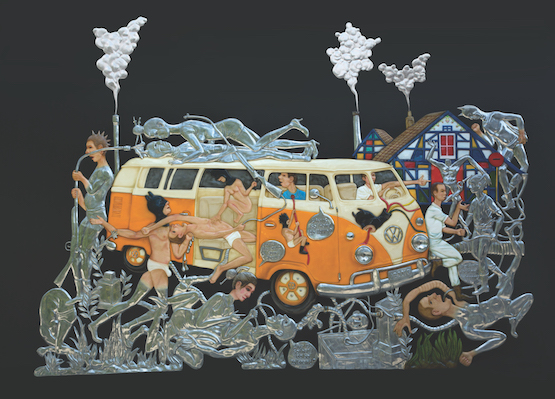

Entang Wiharso: The images in my work are a visual language that reflect and describe signs and confirm symbolic ideas I have about culture, history, community, the state, systems and experiences. The crowd and bustle present in my work is a way to present the conditions that exist in Java: a teeming and chaotic island that has experienced accelerated, sporadic changes. For someone experiencing this environment for the first time, it is difficult to see the structure yet the disorder itself is a structure that provides benefits to many people.

I worry, though, that living in these conditions makes it difficult for us to think deeply. Perhaps the chaos, speed and a kind of short-cut mentality in Java are the body’s response to the movements and geological conditions of the island itself.

The Indonesian archipelago lies at the confluence of two tectonic plates and was formed by eruptions and earthquakes. These forces and vibrations are always active. Tropical rainforests are considered to be the most complex ecosystem on earth. I think environmental conditions affect the body’s neurological system. In addition to the highly diverse and productive environmental conditions, the development of the Javanese people can be understood in relationship to their acceptance and rejection of the past and the present – the history of political structures though the kingdoms, colonization, independence and globalization. People are often only aware of a small fragment of a much larger narrative that they experience. Connections to the past, to geology, are often overlooked or go unnoticed. All these fragments are like parts of a large, complex ornament and each fragment is essential to the structure. My work, with the crowded, interconnected mise en scene is a manifestation of this idea that every element plays an essential, equivalent role. Large and small elements are equally important, each critical to the whole. Moreover, I delineate the density of figures to explore turmoil and equality.

Image: Entang Wiharso, Coalition: Never Say No, 2015,. Aluminum, car paint, 200 x 300 cm.

Sally Smart: I set my installation work, assemblages and collage constructions very specifically in their conceptual place. This process might be activated by experience or the imagination. In most cases, I develop and create an idea from source material, photographs, literature and models to build a symbolic picture. The process unfolds through this initial gathering – to visualise into painting, drawing, constructing, amplifying, distilling, cutting and pinning, over and over till the energy of this process synthesizes or reveals what appears complete, and the assemblage is resolved.

My mise en scene might be described variously through the garden as the site in collage performance works (In Her Nature, 2012, 2015), (Family Tree House, 2000-02); abstracted interior space (Femmage Shadows and Symptoms, 1998, 2004); a blackboard or theatre set (The Choreography of Cutting, 2012-15), seascape (The Exquisite Pirate, 2005-10, 2015 ) and within a grid structure describing architectural space (Design Therapy, 2002 and Daughter Architect, 2004, 2015).

I create collage elements in relationship to each other, in harmony and with discordant details used to emphasize psychological and emotional intensities including humour. I am interested in subverting a narrative despite the representation of figures pulling the reading toward that conclusion. Never neat and seamless, pins are exposed, elements abstracted and I reveal the cuts that make these collaged assemblages.

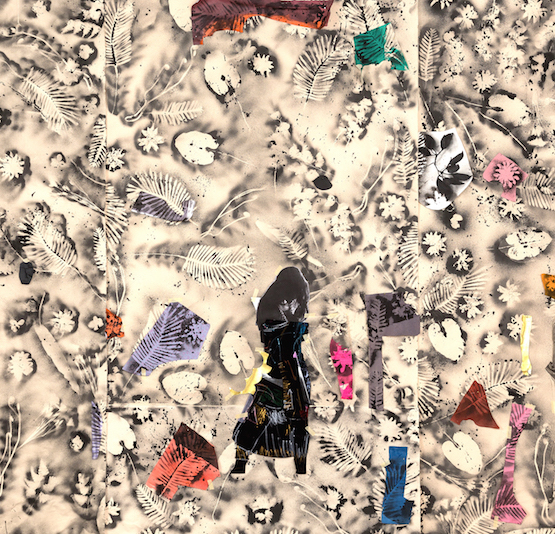

Most recently, I have developed the space of the blackboard, walls with chalk notations and cutout figures to create a dance to extend the examination of the body and movement revealing the act of the process. Titled The Choreography of Cutting these installations, collages, paintings, performance, puppetry and video works look at dance choreography and how it connects to the collage methodologies in my practice generally such as the movement of elements in space; improvisation and rehearsal; and actions of cutting and assembling described and visualized in drawing.

I combine this process-oriented practice of cutting, collage, photo-montage, staining and pinning as methodologies integral to the conceptual unfolding of this work, and relating to femmage: a term created by the American feminist and theorist, Miriam Shapiro to describe her collage works and women’s historical connection to making including collage, photomontage and embroidery, linking to these political feminist origins.

I have investigated choreographers’ drawing via notations and marks used to render, map, define and describe a movement or a sequence of movements or a feeling. The ‘cutting’ in the work’s title directly references my collage practice (where I draw with scissors and blades) and the psychological condition of self-cutting often described as delicate cutting. The work draws inspiration from various dance repertoire (including Martha Graham’s choreography and costume for the major performance Appalachian Spring). These assemblages of performance point to the physical body’s capacity to express a collective and individual anxiety. I explore my process of making, drawing and cutting and how it might align to choreography, to image thinking in movement.

Sally, can you elaborate on how dance and choreography have become central motifs in your practice, embodying movement, action and transformation?

Sally Smart: I am interested in how a dancer’s movement at its extreme can transform emotional and psychological intensities, almost simultaneously. In 1996, my exhibition of paintings titled Delicate Cutting made connections with body scarification and cutting to explore issues of identity politics. The term delicate self-cutting describes the self-harm neurosis of cutting the body as well as showing the marks of that action. I am committed to the politics of cutting (a term I use) through exploring cutting processes in art (drawing and performance) and their connection to the body (psychologically and physically).

Cutting can act as an inscription between the world and the body. Along with these ideas of identity and gender politics, I was also drawn to representing the unstable nature of identity. It was also a methodology to explore the body, using and referencing medical metaphors to dissect and analyze concepts and techniques. Over several decades my work evolved into more complex assemblages using all these references of cutting and collage and photomontage. I use materials that are integral to the conceptual unfolding of my work along with these processes of cutting, pining and staining. Increasingly, I have wanted to make cut-out work that relates to my interest in choreography and dance.

In 2012 I was the University of Connecticut’s, USA, Raymond and Beverly Sackler Artist-in-Residence and produced a new body of work that included an exploration of time-based media and performance. The Pedagogical Puppet Projects developed and I worked with choreographer’s drawings, looking at how dance movement might be described and documented visually leading me to show the process of my thinking/mapping/planning through diagrams and notes. Specifically, I was researching Rudolf Laban’s drawings (a pioneer of modern dance in Europe, who was also the dance teacher to the artist Sophie Tauber Arp) and the philosopher Rudolf Steiner who used puppets in his teaching and blackboard dissertations to impart his knowledge (this drawing and writing was influential to Joseph Beuys). I was inspired to use the blackboard to document my notes/writing ideas/daily meetings at the University, as a visual connect to the pedagogical process.

The choreographer Martha Graham and Pina Bausch and the early modernist artists associated with performance, especially Hannah Hoch and Sonia Delaunay are important references to this work. I assembled large scale installations of cut-outs made from painted and constructed elements, photographic, silkscreened and patterned fabrics, including black velvet, inscribed (scribbled and scrawled) with oil pastel marks and notations, referencing choreographers’ drawings (historical and contemporary) with the drawing detail, marks, arrows and notations resonating movement further reinforced in the poses of the figures and costumes.

Image: Sally Smart, Choreographing Collage, (detail), 2013. Synthetic polymer paint and screen print with various collage elements, video, steel, cotton, string, rope, cardboard, pins, photographs, chalk, pastel and glue all on canvas, 350 x 1150 cm.

Die Dada Puppen, 1996, and Artists Dolls, 2012, 2015, are assemblages, artifacts and processes of performance developed from my interest in the early avant-garde and identified with the art practices of Cubism, Dada and Surrealism (Sonia Delaunay, Hoch, Popova, and Taeuber); all great exponents of work with performance and puppets. Shadow puppets have long been in my practice exemplified by silhouettes and movement. I have been influenced by wayang and have amassed a personal collection of wayang kulit.

Entang, how are you working with Indonesian mythologies and traditions for Conversation?

Entang Wiharso: I grew up in a society where reality and mythology mix, overlap or crossover each other. Though mythology is imbedded in my culture, my work doesn’t deal with mythology as a subject. I analyze society’s behavior and represent this in my work, and this is the juncture where mythology enters my practice. Humans have always turned to mythology as a cultural response to the unknown. Sometimes it is difficult to separate mythology and reality. It can seem that mythology becomes reality or reality become mythology. I remember when Soeharto, the former president of Indonesia, mythologized himself as the god Semar. He aligned himself with this potent mythical character, familiar through puppet performances enacted across Java, to create a legacy of wisdom and super power. There is also a very strong oral tradition in my culture and this is reflected in the narrative elements in my work. The Javanese save information garnered from friends, parents, the government, religious leaders, and traditional leaders and so on in their minds. They pass on the information verbally, and this is an aspect of mythology that I also explore in my work.

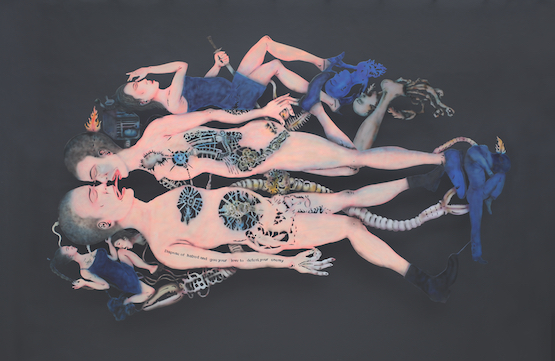

My visual language is based on ideas. For example, I use transformation, or a kind of human-to-animal evolution, such as changing the feet from human to goat and distorting the human tongue to resemble a dog tongue, to express a variety of conditions. We often find this kind of imagery in Greek myths as well as Indonesian culture. Every civilization across the globe has myths that respond to nature or human behavior and function as warnings, education or sanctions designed to protect important cultural beliefs. I visualize a sort of evolution, a transformation or mingling of forms, to explain ideas or concepts through imagery of mixed, or hybrid, identity or culture. I create visual narratives about ethical issues or problems – morality, human acts, politics, loyalty, identity, technology, modernization vs. tradition – by creating images that people identify with from mythology. Actually I am building a lexicon or dictionary, a personal visual code, to communicate visually. I want to express my opinion through a strong visual language.

Image: Entang Wiharso, The Other Dream: I love You Too Much, 2011-2015. Aluminum, car paint, resin, thread, color pigment, 275 x 400 cm.

For example, depictions of the human tongue that transforms into a snake or fire refers to how the tongue is a powerful organ that can be used as a tool to create manifestos, influence, lies and propaganda; or the tip of the tongue turns into a crab leg to discuss clichés about Indonesia as a nation of idlers who just talk and walk slowly; or the tip of the tongue turns into a hand holding a knife to depict back stabbers or traitors. Another example is the transformation of human feet or legs in my work. When the foot transforms into a lamb’s foot, this constructs a narrative about how people become the victims of propaganda or indoctrination, where there is a loss of reason and tolerance. They are transformed into animals, or animal instincts arise. It also relates to the theory of evolution in which humans evolve from animals; or it expresses the two sides of man – our human nature and our animal instincts.

The imagery of human and animal reflects dehumanization or ethical compromise. Why do people, for example, want to become suicide bombers, kill themselves and their neighbors? The instinct to violence in animals is related to survival; for humans, violence can be a means to achieve power, enforce an ideology, gain approval and experience pleasure. When the foot becomes a dog paw it describes loyalty, as well as the blind loyalty that can cause us to harm ourselves. I use it to discuss war or the tendency to follow a bad system blindly during times of crisis, following orders from superiors, political or religious leaders who don’t think about the long-term outcomes, and use loyalty, fear and sanctions. Like a dog with its owner, the dog is always loyal and will perform whatever orders are given. The use of human or animal skin is used to visualize the loss of our humanity, a tendency toward intolerance, and the rise of malignant or brutal human actions. Skin also refers to issues of identity, rooted in race and ethnicity: the difference of skin. This can be seen in works such as Chronic Satanic Privacy, 2010; Temple of Hope, 2010; and Black Goat vs. Aesthetic Crime and Identity Crime, 2010. In recent works like Dream Machine, 2015; A thousand KM, 2015; and Feast Table – Being Guest, 2014-2015, images of humans turning into machines, or with machines parts, describe the effects of technology: how devices are merging with our bodies and how our environment is filled with electromagnetic energy constantly sending messages to our neurological systems.

Unconsciously, the human body has become a mediator/conductor for electromagnetic energy to disseminate signals or information. In these depictions, I often visualize humans with robot arms or with brains full of cables or bodies made up of machines. In addition, in Dream Machine, the four-eyed main figure is used to talk about double identity or cultural or genetic hybridity. Depictions of multiple eyes are also often portrayed in the Ramayana. For instance there is a character named Dasamuka, meaning ten faces. This figure of Dasamuka possesses superpower because it can change its face to fool its enemies and lovers. Imagery in my work is the way I make codes to build a large narrative structure to help me convey ideas through visual language.

What are some of the key confluences between your work? How has your conversation been ignited?

Sally Smart: There are some obvious visual connections to cutting but what has become more apparent are the profound professional, intellectual and emotional confluences: a true friendship has emerged. This can be measured in the evolution of the title for our exhibition, it started with CONVERSATION and over time the realization grew that this was not a short converse. We wanted our conversation and our exhibition title to engage philosophically with our thinking. Our ideas, stories and events, imagined or real, mythologized or concocted were in a continuum and could be understood as the endless acts of human history.

Entang Wiharso: I have many friends who are artists from Europe, the US and parts of Asia, but Australia was always a blank spot for me. In 2012, I participated in a group exhibition, Closing the Gap, followed by a pop-up show with ARNDT and then a residency in Melbourne where I met Sally. I felt like I had finally found Australia. When we met at Gertrude Contemporary at the tail end of my residency, Sally and I clicked. She felt familiar and the conversation was stimulating. Since then we have become friends. This joint project is a form of collaboration that stems from intensive conversation between two artists – a collaboration that expands, rather than contracts. I'm not interested in finding common ground or looking for differences but I am keen to voice my ideas in space and time together in one forum.

The collaborative aspect is through conversation and a joint exploration of ideas that have been discussed endlessly through human history. I mean, we are interested in the strange ways in which our lives have segued or the unexpected parallels that can be found, but for me, the collaboration between Sally and I exists in the realm of the intellect and in the exploration of essential ideas that we all experience and struggle to understand. From conversation to conversation there is a growing consciousness and a meaningful proximity that has led to our exhibition: a sign, as well as a statement, that we trust each other and have reached an understanding. The exhibition is the end of the first half of a collaboration that matured organically and opens the next round of conversations, with an outcome that we cannot predict. My friendship with Sally is a continuous, complementary and organic sharing of information.

As global citizens working across borders, how do you navigate boundaries and cartographies, perhaps akin to endless acts in human history?

Sally Smart: I have long been interested in the surrealist artists subversive strategies to dissolve borders and reject nationhood. These philosophies about art and politics can be seen in their exquisite corpse game – elevating this parlor game into art through the imaging of hybridized corporeal zones with leaking and spilling bodies and borders.

In 2004, I began a series of work The Exquisite Pirate which has evolved as an idea through numerous iterations globally, and offers the woman pirate as a metaphor for contemporary global issues of personal and social identity, cultural instability, immigration and hybridity. The symbolism of the ship and its relevance to postcolonial discourse.

Image: Sally Smart, The Exquisite Pirate, 2006. Exhibition view, mixed media, Postmasters Gallery, New York, USA.

My work places a practical and theoretical emphasis on the installation space, on mutable forms and methodologies of deconstruction and reconstruction. The project initiated from a simple question – “were there any women pirates?” In tandem there evolved vast popular culture imagery connected to pirates and references in the media to cyberspace activities. In contemporary and historical Australia, the boat and ship have loomed around immigration issues and for me have become expressive, powerful images for postcolonial discourses at the same time subverting the historic perception of piracy as a male domain.

Without glorifying the lawlessness of the historical woman pirate, my work proposes a figure of indeterminate identity as a way of thinking about a globalised world and the need for strident, alternative opinions. In the Galeri Nasional Indonesia exhibition I will install elements from existing work and combine for the first time embroidery. The Exquisite Pirate (Jawa Sea), 2015 will use the grid format as the underlying structure to evoke a map or navigational sign to delineate and colonize space. The work will include two ships, pirates and various elements including abstractions of water-blood. Other elements are based on fragments of land mass literally taken from the “surrealist map of the world” a work Max Ernst and other Surrealists created that re-defined the world according to their philosophy. Then, I re-arrange these landmasses in the sea of my installation as a conceptual map, a cartography.

Image: Entang Wiharso, Promising Land, 2015,. Resin, car paint, flat screen tv, steel, wood, 230 x 430 cm.

Entang Wiharso: I am physically separated by a variety of borders but mentally systems, structures or geographic borders do not limit me. Art is a tool to reject the limits of land, time, place, culture and community, as well as religious or political borders. Limits exist if we believe that the limits exist. This is the problem with receiving information about limits, but if we negate the boundary itself, it does not exist. Only art can remove all limits because art exists through space and time and is always relevant.