Ingrid Schaffner

Ingrid Schaffner. Photo: Bryan Conley.

Ingrid Schaffner. Photo: Bryan Conley.

Founded by industrialist Andrew Carnegie as part of the Carnegie Institute in 1895, Carnegie Museum sought to 'bring the world' to the city with a grand building housing a natural history museum, a library, and an art museum operating as a fluid space for knowledge exchange. In its 123-year history, the institution has built up a world-class collection of over 32,000 visual art objects. In 1896, just one year after the launch of the Venice Biennale, the Museum launched the first Carnegie International1 exhibition, which happens every three to five years. This led to the acquisition of Winslow Homer's The Wreck (1896) and James A. McNeill Whistler's Arrangement in Black: Portrait of Señor Pablo de Sarasate (1884), the first painting by Whistler to be acquired by an American museum.

The 57th Carnegie International (13 October 2018–25 March 2019) is grounded in the word 'international'. This year's edition is curated by American curator, art critic, writer, and educator Ingrid Schaffner, who previously directed the exhibition programme at the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) at the University of Pennsylvania between 2000 and 2015, where she initiated exhibitions such as Queer Voice (22 April–1 August 2010) and Pathways to Unknown Worlds: Sun Ra, El Saturn & Chicago's Afro-Futurist Underground, 1954–1968 (23 April–2 August 2009).

To curate this edition of Carnegie International, Schaffner undertook five research trips with the goal 'to expand [the] sense of the word "international" by getting off the beaten track', leading her across the globe to locations such as the Caucasus, Senegal, the Philippines, and Nigeria. Staged solely in the Carnegie Museum of Art, with some spaces shared with the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, works by 32 artists and collectives, and one exhibition maker (Koyo Kouoh, presenting Dig Where You Stand, an 'exhibition within the Carnegie International exhibition'), are shown throughout the museum's various galleries in solo and group displays that grapple with the 'international' that defines the museum's identity.

Postcommodity—an artist collective comprised of Raven Chacon, Cristóbal Martínez and Kade L. Twist—avoid a simple interpretation of 'international' by processing historical events through an indigenous lens. The result is a moving installation titled From Smoke and Tangled Waters We Carried Fire Home (2018), which was assembled in the traditional Navajo sand-painting style and made from glass, steel, and sand culled from local industrial sites. The work pays homage to the erased history of black labour that built Pittsburgh and contributed to the evolution and history of jazz in the city. All of these materials will be returned to their original sites of excavation at the end of the exhibition.

Visitors to the exhibition are encouraged to leave their preconceptions about contemporary art at home, with Schaffner placing central importance on the notion of delight and joy in the museum-going experience, even when dealing with contemporary global issues such as migration, coloniality, conflict, and nationhood. This 'joy' comes from a place of seriousness that beckons further thinking about how the museum can be a space that is disruptive, fluid, in flux, and live.

This sense of play was articulated in a number of ways, including Schaffner's approach to building on past editions by showing previously exhibited work, or reusing locations used in previous editions. Take Yuji Agematsu's zip: 01.01.17 . . . 12.31.17 (2017), an intricate installation of miniature sculptures made from his obsessive collecting of debris during daily walks: the work is located in the same space where On Kawara's Today was originally shown in the 1991 edition. In another gesture of excavation, Park McArthur dug into the museum's built history by establishing that the museum's stones are made from larvikite stone and dispatched a sound engineer to the now defunct quarry in Larvik, Norway to record sounds, which are now transmitted throughout the Courtyard Entry lobby and a section of the upstairs Scaife Galleries.

Another remarkable installation is Alex Da Corte's Rubber Pencil Devil (2018): a massive illuminated neon house containing 57 videos in its porous, dreamlike interior that combine pop culture, personal narrative, art-historical references, and television characters such as Fred Rogers from the hit PBS children's show The Neighborhood of Make-Believe (filmed in Pittsburgh) telling a story of contemporary America.

In the conversation that follows, which took place during the opening of the 57th Carnegie International, Schaffner discusses the curatorial framework and choices for this year's show as well as a return to the museum as a site for joy.

JDRather than operating as a theme, the word 'international' grounds the 57th Carnegie International. How did notions of travelling across time and space come into unpacking this word as a curatorial impetus for the exhibition? I understand as part of your research you travelled extensively with a number of 'Travel Companions', including Carin Kuoni, director and chief curator of the Vera List Center for Art and Politics, The New School, New York; Bisi Silva, founder and director of the Centre for Contemporary Art (CCA) in Lagos; Doryun Chong, chief curator of M+ in Hong Kong.

ISWhen you do an exhibition of this scale and the art world is your field, you realise that it is impossible to cover everything in one project. This was an opportunity for me to get off my own beaten path, and as much as the art world is global/international, we all end up on similar routes and looking at the same things. I wanted to travel to art worlds that might be new to me, but then there was the issue of figuring out where to go.

The Travel Companions I went around the world with were in part motivated to act as a catalyst to follow the trajectories of their research; it provided a way to travel to art worlds new to all of us. I also wanted to think differently about the long history of having art advisors for the International. The trips came with the caveat to travel somewhere neither I nor the curators I invited to accompany me had visited, as opposed to going to the places where they operate and connect to the same set of artists, curators, writers, and institutions they would normally introduce visitors to. It was also a way to bring in degrees of serendipity, openness, and vulnerability.

Carin Kuoni is a friend and collaborator with whom I have worked closely on many projects over the years. We travelled to Marrakech, Dakar, and Lagos. With Doryun Chong, the intention was to travel to Bangladesh and Pakistan, but due to terrorist attacks this was not possible, so we settled on India, a country we had both visited in the past but has changed from an emerging contemporary art scene to a more established one over the last ten years. Ruba Katrib is a rising curatorial voice whose work I admire. She was interested in going to the Caucasus region, so we went there, while Bisi Silva suggested we continue her research on art of the African diaspora that had taken her extensively to South America but not to the Caribbean. Magalí Arriola had an interest in following colonial trade routes between Mexico and the Philippines, so that took us to Southeast Asia.

Would the Caucasus and the Caribbean have been on the top of my list as places with a visible art world to explore? No, so it was great to be taken into new parts of this field. With each of these Companions and their proposed locations, there was a dispersal of both time and place in terms of where people were with their curatorial work. Each trip was really built in terms of itself.

My colleague Liz Park [Associate Curator, 57th Carnegie International] researched itineraries for the trips and, with leads from the Companions, we set off on these rigorous journeys with the criteria not just to visit artists in their studios, but to also get a sense of how the contemporary takes hold in other parts of the world through spaces, places, publications, and so on. It wasn't to define artists for the show but more to establish a deeper understanding of the networks and linkages across the contemporary art world, and how provisional these sometimes are and how hard these connections are to make, but also how strongly they exist. These structures were something I wanted to build with the International, starting with things that were familiar to me and how they linked to works I encountered in these travels.

JDAside from the Travel Companions, you introduced an 'exhibition within the Carnegie International exhibition' with Dig Where You Stand, curated by Koyo Kouoh, an exhibition maker, cultural producer and the founding artistic director of RAW Material Company in Dakar. How did this come about?

ISKoyo Kouoh's project Dig Where You Stand is emblematic of the curatorial at work and how the field is connected by writing, exhibition-making, conversations, residences, and all of the spaces and places that make these possible and are truly expanding the contemporary art field. When Carin and I were in Dakar for Dak'Art in 2016, we met with Koyo, who made it clear that coloniality drove all of her curatorial work. This was something that stuck with me and I invited her to bring this approach in a pervasive way to dig through the Carnegie Museum of Art's collection.

The spaces that Kouoh's project inhabits for the International historically displayed non-Western and African art. This was a problematic space with no curatorial expertise, which followed the usual art historical linearity within Western art history—cave paintings to the emergence of Modernism, and so on. Koyo's project acted as a lever not only to rethink these galleries but also to think more broadly about the objects which this museum is a steward of, and how we can construct new narratives, which she did. The viewer comes out of Dig Where You Stand and things just feel different.

JDA project of this scale and significance is no doubt challenging to put together and organise curatorially; how did you decided on the exhibition's flow within the museum, given the many entry points weaving through the historical, contemporary, outside, inside, and the many in-between spaces that have now become animated with artworks? A revelatory moment for me was getting lost and encountering Jeremy Deller's Breaking News (Dedicated to Peter Watkins) from the 54th Carnegie International in 2004, exhibited again in this year's edition in the Hall of Miniatures.

ISOne thing that is remarkable is that the museum really gives itself over for the International. It really is a show that the museum is very committed to, which is not to say that it is easy; everything has to be negotiated, but you do feel when you come in as the curator there are a lot of possibilities to work with the museum itself. For example, Kevin Jerome Everson's film Park Lanes (2015), which is 480 minutes long and details a day in a factory in Mechanicsville, Virginia, is projected in the pit of the museum's Grand Staircase right next door to the office of the director of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History [Eric Dorfman]. He will be listening to grinders for the next six months!

The exhibition is constructed in terms of siting and inviting artists to inhabit certain spaces; I really wanted to create a flow throughout the museum that encourages visitors to encounter the exhibition in unexpected ways. There was also a problem I wanted to address, as I was born in Pittsburgh and the Carnegie Museum was the first museum I visited. When I was a kid you could go from natural history to art and into the library. They were all connected and free, and I'm sad to see how these different buildings have been sealed off from one another. There's a criticality in introducing this flow that takes visitors to the collection but also attempts to open up these sealed spaces. The performance Postcommodity [Kade Twist and Cristóbal Martínez] created with the installation From Smoke and Tangled Waters We Carried Fire Home (2018), located in the Hall of Sculpture, will see the doors to the Hillman Hall of Gems & Minerals open for the first time since the 1970s as the music flows between these two space for the duration, creating a disturbance.

JDWhy did you include works from previous editions of Carnegie International as traces, and how did you connect them to the current edition?

ISThis was partly because I was quite tired hearing about how guest-curated exhibitions were erased from one edition to the next. The museum has been formulating a contemporary curatorial practice by inviting guest curators for the Internationals since 1991. I wanted to think about this iteration as not doing away with what came before, but building on ongoing curatorial research within this frame of the contemporary. There are a lot of decisions that are also structural, like Yuji Agematsu's zip: 01.01.17 . . . 12.31.17 (2017), which is located in the space of On Kawara's Today from the 1991 edition; both are calendrical works.

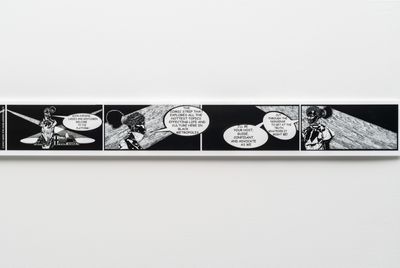

I invited Jeremy Deller back in part because those miniature TV screens are so ephemeral, and I love the idea that you could blink and question whether they were really there or not. Ten years later they are back as an act of social surrealism (Deller's term)! Zoe Leonard's Prologue: El Rio/The River (2018) is the beginning of a much larger body of work investigating the Rio Grande, whilst Kerry James Marshall's Untitled: Rythm Mastr Daily Strip (2018) was first created for the 1999 edition as a multipart comic strip distributed through the local newspaper, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. I had the idea that we could recirculate this issue but in conversations with the artist, he decided to redraw this work and bring it into his current vocabulary as a black and white, really graphic comic strip. An artist returning to a work to rethink it is one of the strategies to making exhibitions like this generative.

JDCould you explain the importance of bringing in the W.A.G.E (Working Artists and the Greater Economy) certification for this edition? Particularly when thinking about the disparities between artists fees for biennial-style shows?

ISW.A.G.E is an organisation that advocates for fair pay and establishes sustainable labour relationships for artists. Disparities do exist depending on the support an artist receives from galleries, patrons, and so on. W.A.G.E set up a structure to compensate artists for their contributing content (artwork), so everyone gets the same fee. This International is certified but it doesn't mean that the next one will be, though discussions around compensation are becoming more open, which will enable thinking of how this area might be improved.

JDWhy did you centre all of the efforts of this edition within the museum and not extend the exhibition across Pittsburgh?

ISI love going to large-scale exhibitions like Front International in Cleveland and Prospect New Orleans where you get to go explore the city; however, whilst other editions of the International have travelled out, I felt at this point the museum needed to marshal all of its energies into exploring this specific site. I am asking people to find their way within the confines of the buildings, which in a way is similar to going out and finding your way through the city.—[O]

—

1 The name of the exhibition has gone through many changes. It was renamed the Pittsburgh International and became biennial; in 1955, it was decided to present it every three years. During the 1970s, the name was changed to the International Series. The show returned to the original 1896 anthology format in 1982, and the name Carnegie International was adopted. https://cmoa.org/about/history-of-the-carnegie-international/