Jarrett Gregory

Jarrett Gregory, curator of 'What Is To Be Done?' at The Armory Show, New York (2–5 March, 2017). Photo: Jonathan Urban.

Jarrett Gregory, curator of 'What Is To Be Done?' at The Armory Show, New York (2–5 March, 2017). Photo: Jonathan Urban.

The news was still embargoed when I sat down with her at The Armory Show last weekend, but now it's public knowledge that Jarrett Gregory has been appointed as curator at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C.—the iconic building that The New York Times called 'the bunker or gas tank, lacking only gun emplacements or an Exxon sign' in 1974.

A rising star, Gregory has been a free agent since December last year when she left her role as associate curator of contemporary art at another of America's best art museums, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA).

In her new role, Gregory will work under chief curator Stéphane Aquin and director Melissa Chiu. Chiu is the wife of Ben Genocchio, who is director of The Armory Show (2–5 March 2017), where Gregory curated this year's impressive Focus section entitled 'What Is To Be Done?'.

Previously, Focus has centred on a particular region—Africa last year, and China in 2014—but in 2016, Genocchio told us that this year there would be a change of direction. Trying to drop a GPS pin on artists working between two studios for galleries in a third country showing at fairs in a fourth to collectors visiting from everywhere else didn't seem to make sense.

Then, the Trump administration grabbed globalism by the pussy, limiting travel from specific countries—Iran, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Libya and Yemen—and singling out Mexico for its bad hombres. Suddenly US borders were demarcated more emphatically than they had been in years.

MoMA responded by hanging works and scheduling screenings by artists from predominantly Muslim countries. Planned out last year, Gregory's selections weren't as laser precise but without a geographical emphasis, her Focus section was hardly diffuse. It felt very salient, capturing the sense of urgency many feel in the face of escalating global injustice.

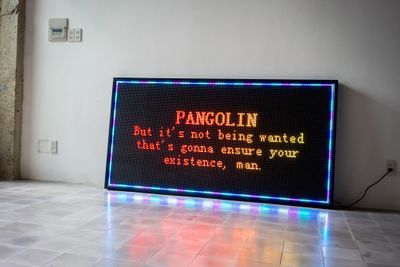

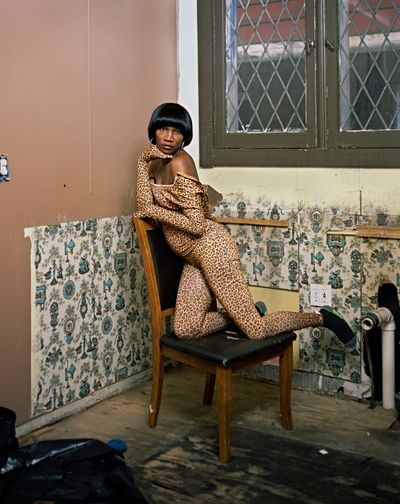

Among the works included in the show was: Johan Grimonprez's film blue orchids (2017), a visceral enquiry into the world of arms dealing; chocolate sculptures of an imagined art collector made by Jérémie Mabiala and Djonga Bismar, members of a collective of Congolese plantation worker-artists called Cercle d'Art des Travailleurs de Plantations Congolaises; and walls of Jute sacks stained black with coal, machine oil, and the soot from smoking fish that Ibrahim Mahama acquires by trading them for newer textiles. Other works, including photographs by Deana Lawson and an upside-down video of dancers in a Nairobi slum, are less overtly political, but not by much.

In this conversation, Ocula spoke with Gregory about her curation of the Focus section at the fair and travels to the Congo.

SGYou were invited to curate this year's Focus by director Ben Genocchio, correct?

JGBen Genocchio, Debbie Harris and I met together. I went through some ideas and my list of artists, and Ben shared his vision for the fair. It was at this point that they officially invited me.

SGWhen did you come up with the theme for the Focus section, 'What Is To Be Done?'

JGIn the summer of 2016.

SGThere are elements of it that seem prescient—the title alone captures how many people are feeling. There's both the dismay—'What Is To Be Done?' as a rhetorical question, implying there's no way forward—and then something more prescriptive—what really can be accomplished in the face of entrenched capitalistic, undemocratic, uncaring systems? The fact that the title comes from a Russian novel, written by Nikolai Chernyshevsky in 1863, is almost too good to be true. Had the election gone a different way, would this theme have been as pertinent?

JGAfter the US elections, 'What Is To Be Done?' is a question most people are asking themselves more frequently and more publicly than we were before. When Obama was in office, there was a general feeling that things were okay, even though I don't think they were. Johan Grimonprez's film addresses the hidden structures, corruption and problems that aren't part of our collective conscience; that's what I wanted to bring to the fore. I don't mean to downplay the US elections, but in some ways nothing changed.

SGGrimonprez's film shows both aspects of 'What Is To Be Done?': firstly in the dismay of both interviewees—arms dealer Riccardo Privitera and former New York Times war correspondent Chris Hedges—who both pretty clearly have PTSD, but also in a plan of action, with Hedges saying hostilities are directly due to arms dealing, not Islam, and that it's something that can be decreased. (Although, the US and China have both announced increases in their military budgets in the past few days.) How do you think about the title? As one of dismay or a call to action?

JGThey're so linked for me; it's one quickly followed by the other. In the novel, it is the same way: despair followed by action. Chernyshevsky's solution is a very utopian socialism that's quite beautiful. I'm not calling for that model but I do appreciate that he offers a solution, and I think we're all looking for one.

SGIn your introduction to the Focus section, you say it's broadly about artworks that are socially engaged.

JGIf you're trying to sum it up, you could say that.

SGDoes that imply that social engagement is not particularly well covered by other parts of the fair?

JGNo. I have been here in the Focus section almost exclusively, so I haven't seen much of the rest of the fair.

SGYour choices of social engagement do have a geographical element in that you're going out to places where there isn't necessarily a huge established art market, like there is in Beijing.

JGDefinitely. Geography is incredibly important. I love this quote—I don't know where it comes from—'the more you travel, the larger the world gets, not smaller.' I experience that. I guess I have taken a lot of interest in places where I can have meaningful conversations with artists. For example in Moscow.

Everything moved very quickly; I almost immediately formed a network of curators, writers and artists. Because of censorship in Russia right now, many exhibitions take place in people's apartments. People are used to organising events on their own. Through Pussy Riot, I met a correspondent for The Economist who put me up for a week during my second visit. I gave a a talk about my work in his apartment and many artists came. We projected a Power Point on his living room wall. You have to be very open or this can't happen, which is probably why people think there is a lot going on in Moscow, but that's not true.

SGSounds like China during the 1980s. Artists used to take photos of their works and then take the undeveloped film around for people to look at by holding it up to the light. How did the Moscow trip come about?

JGIt came about because I went to see Urs Fischer's show at Garage. While I was there I was introduced to a critic-curator who started taking me around to different studios including Ana Titova's, who we're showing here. Every time I met somebody I was introduced to somebody else. Since then, I've talked to quite a few curators who will very offhandedly say, 'Well there's not really much happening in Russia', which I couldn't disagree with more.

A lot of curators travel, but what I've wanted to do is spend time and get that third introduction that takes meeting the friend of the friend of the friend and going a bit deeper. I had dinner with Nadia from Pussy Riot in LA; she was recording her album there, and so I was put in touch with her husband, Pyotr Verzilov, who's in Moscow. While I was there I got an email saying that Petr Pavlensky, the artist who had done all these performances like setting a fire in front of the doors of the KGB building, would be released from prison. So I met Pyotr at the courthouse: it was an open thing but you had to know when and where to be and maybe only 30 people fit into the room. I was able to witness this and Pyotr translated for me.

SGIt sounds so epic, so historic.

JGDefinitely. For me the trip was also important because it helped me to see things from a different perspective. One of the things that really surprised me when I first arrived in Russia in June was that many people said to me, 'Oh America, you're like us. We have Putin, you have Trump.' This was long before the elections.

SGThere are a few different ways of describing a curator's role. You seem to be especially interested in the discovery—the archaeological dig of contemporary art.

JGI'm not so interested in finding the new just for the sake of what's new. But I am really interested in having conversations across cultures and getting to understand a context as best I can.

I'm obviously not living within these cultures, so it's still superficial in some ways, but I feel like a big part of my job is understanding what I'm showing when I include it in an exhibition.

SGDo you feel like many people don't have time for work that is socially engaged? They think that it belongs to another realm such as journalism, and that it's not high art in some sense?

JGI've been trying to play with that idea because a lot of the works in this section have a social element, but that's not really what defines them. They're strong artworks in and of themselves. I've been thinking a lot about the definition of political art and if there's a way to think about social engagement or political art that's much more nuanced. I've also been thinking about whether a work can be intrinsically political if it's simply aware of its local conditions and demonstrates awareness. I'm also interested in works that involve modes of engagement or exchange that are not necessarily perceptible or known. Somebody like Deana Lawson is a perfect example; for me, her photographs are incredibly powerful, so much so that what happens in order for her to make them doesn't really matter. But if you know how she works, her process becomes just another facet that one can become affected by—and I have been.

SGAnother far-flung place you travelled in preparation for this show was the Congo, right?

JGThat was in September. I became familiar with Renzo Martens' project through seeing his documentary Enjoy Poverty (2008) [in which the filmmaker examines poverty in the Democratic Republic of the Congo]. After doing some research online, I found out that he was organising a conference in September in the DRC. Renzo and I were already in touch, so I wrote to him and asked him if I could please come for the conference. They helped me organise the logistics.

SGWhat are the logistics of getting there?

JGI needed a visa, which is actually quite hard to get as an American, so I had to have a special letter from the Minister of Culture; getting that was a bit challenging, but it worked out. The people from the Institute of Human Activities who work on this project were there in Kinshasa when I arrived, so they met me at the airport and traveled with me to Lusanga, where the conference was. We spent a night in Kinshasa at a guesthouse and then we flew on a tiny plane to Kikwit, which is a quick flight but a 8 hour drive from Kinshasa. There's quite a lot of corruption in the Congo so sometimes logistics involves additional 'fees', not unlike bribes.

SGDid you witness anything like that?

JGI didn't, but I know it takes place.

SGExciting?

JGIt felt unpredictable. My visit was right after riots took place, as a result of conflict around the elections. Seventeen people had died on the streets the day before I flew. I was in Brussels when that happened. Renzo and I got on the phone because a few speakers had cancelled. At this point Renzo and I still hadn't met, we had just spoken. He talked me through it and said he thought it would be fine but he would understand if I didn't want to go. After getting the visa, I wasn't going to get scared off easily. I think he thought I was a little bit nuts because so many people had cancelled and I wasn't concerned, especially as a young woman flying alone to Kinshasa in the middle of all this turmoil.

SGDo you think you're a little bit nuts?

JGNo, not at all. I lived in LA for five and a half years and I think driving in Los Angeles is more dangerous than going to the Congo, honestly, and that's a risk for no gain. So to take a risk and know exactly why you're doing it—that seems smart.

SGBut you'll be working in another dangerous part of the world soon.

JGI'll be starting at the Hirshhorn in D.C. —[O]