Luba Michailova

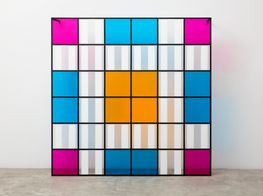

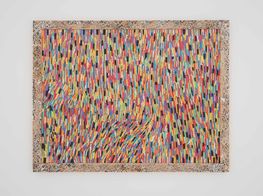

Image: Luba Michailova. Photo: Dima Sergeev. Courtesy of IZOLYATSIA.

Image: Luba Michailova. Photo: Dima Sergeev. Courtesy of IZOLYATSIA.

IZOLYATSIA is a non-profit non-governmental platform for contemporary culture founded in 2010 by Luba Michailova in Donetsk, Ukraine—a territory known in the Soviet era as Stalino, which was seized by the local militia of the self-proclaimed 'Donetsk People's Republic' on 9 June 2014.

Until the seizure of the region, the foundation was housed in a former factory that Michailova's own father once ran, which was built in 1955 as a plant for the production of insulation materials. ('Izolyatsia' means both 'insulation' and 'isolation'.) The intention behind the foundation's establishment, as Michailova once stated, was to stay true to the history of Donetsk, and by association the Donbas region, by creating a platform for art and culture that was rooted to its context. To this end, ISOLYATSIA's founding principle was based on site-specificity, with projects and artworks maintaining a connection to place.

After IZOLYATSIA's Donetsk space was taken over in 2014, the foundation has been housed in a shipyard in Kyiv, where programming has evolved to explore the role of culture before, during, and after conflict, launching iZone in 2015, a multi-disciplinary project that seeks to workshop how contemporary art and the creative sector can produce sustainable models of living together.

In this interview, Michailova discusses the ways in which the foundation continues its activities, while staying true to its founding ideals: to support artists and creative producers throughout Ukraine, while establishing links with the international community, from curators and scholars to artists and ambassadors.

SBYou established IZOLYATSIA in Donetsk in 2010, a region in Ukraine that was established as a separatist (unrecognised) state in 2014. Before we go into what happened to the foundation in light of the geopolitical events at the time, which included the Russian annexation of the Crimea and the Euromaidan movement, I wanted to ask first about the story behind IZOLYATSIA, which you founded in the former insulation materials factory that your father directed.

LMI was born in a very industrial area, where culture has always been of secondary importance, and supposed to serve the 'glory of Soviet industry'; however, culture and arts were always in the centre of my interests. In the late Soviet period, when I was raised, it was impossible to make a career in that field, especially for a person from an industrial milieu like myself, which is why I chose business. Nevertheless, the idea of a cultural enterprise never left me, and by 2010, at the end of my business career, I decided to create IZOLYATSIA at the former industrial site.

In 2010, Ruhr was chosen as the European Capital of Culture, and the example of post-industrial cities like Essen, with its famous Zollverein Coal Mine Industrial Complex, turning into cultural centres was an inspiration for me. This is why the first event held at IZOLYATSIA in 2010 was a conference titled Cultural Conversion: A New Life of the Industrial Past that featured specialists from Germany, Netherlands and Russia with experience of revitalising industrial spaces.

SBYou have talked about a kind of marriage between art and industrial culture in establishing the foundation within this former industrial space. How did the context, and history, of Donetsk—and by wider association Ukraine—feed into the conceptualisation of IZOLYATSIA?

LMThe word 'изоляция' (izolyatsia) literally means 'isolation'/'insulation' in Russian: a name that was inherited from the factory producing insulation materials in which the foundation was housed in Donetsk. This name conveys the idea of preservation, protection from external deteriorating factors, reflecting the precarious state of culture in post-Soviet Donetsk. Back in the 1960s, the Izolyatsia factory was a symbol of new life in the post-war USSR; with around a thousand workers, it supplied its products to all Soviet Republics, Finland and Socialist countries. It also had an important social dimension: hosting a kindergarten, a canteen, a club and other communal buildings, Izolyatsia was much more than a working place for its employees. In the 1990s, however, the factory stopped, leading to the demise of a whole area around it. When I came back to Donetsk in 2010, my idea was to keep the old name, but breathe a new life into it, and my father was the first supporter of this concept.

Whereas in the 1960s industry was the main catalyst of change in the Donbas region, now culture and creativity have to take its place. Since the beginning, IZOLYATSIA was driven by an ambition to implement new economic models in Ukraine, changing its mono-industrial profile to a more diverse landscape of local creative enterprises. So the industrial heritage, which is at the heart of our foundation, is not only about aesthetics, but also about the desire to have a real impact on local communities, the way industry used to do back in Soviet times.

SBCould you talk about those early years, and the way in which the foundation was launched. How did the public develop around it? What challenges did you face at the time?

LMThe main challenge we have faced was to work with the local population, 80% of which has never travelled outside the Donbas. In Donetsk, with a population of over one million people, there were only a couple of old Soviet-style museums and one single commercial gallery. For the majority, culture was limited to either classical ballet or shows after football. In most cases, people did not really understand why contemporary art exists at all and what its purposes are.

Since the beginning, IZOLYATSIA was meant to be an alternative to a traditional museum or gallery where people came to see exhibits. Our first major art project, 1040m Underground by Cai Guo-Qiang, was interactive in nature, as the artist worked closely with local artists, miners and volunteers in creating his gunpowder drawings.

This kind of participatory, site-specific art projects became a staple for IZOLYATSIA, and in four years in Donetsk, we have carried out a string of international exhibitions and residencies, including Partly Cloudy, curated by Hasselblad Award-winning photographer Boris Mikhailov; Turborealism (Breaking Ground), featuring aspiring artists from New Zealand, Brazil, UK, France, Germany, and Ukraine who studied and rethought the local context of the Donbas; Where is the Time? in collaboration with Galleria Continua, inviting artists as diverse as Kader Attia, Daniel Buren, Leandro Erlich, Moataz Nasr, Hans Op de Beeck, and Pascale Marthine Tayou to re-appropriate time through in situ spatial interventions; IZOFON, a musical residency featuring experimental, rock, and contemporary classical composers and musicians giving lectures and creating site-specific music. The philosophy behind all these initiatives was that while we change the place, it changes us in turn.

Gradually, we have built our audience. The first exhibition was attended by a total of 500 people, while our last event in Donetsk attracted 5000 visitors a day. I should mention that our "non-central address" was another challenge: the factory is located at the outskirts of Donetsk and there was only one bus from downtown to IZOLYATSIA. Moreover, local authorities never supported us anyhow—quite the opposite, they were always hostile towards our activities. Back in times of Yanukovych, institutions promoting democratic values and free thought, especially in Eastern Ukraine, were seen as a menace. But despite this, IZOLYATSIA managed to raise a large group of followers in the region and in Ukraine in general.

SBHow did the foundation develop in the four years between 2010 and 2014 alongside how things were moving in Ukraine both in terms of the art scene, and in terms of the political situation as it was unfolding?

LMIn those four years, we have managed to nurture our own art scene, and we have done so in spite of the circumstances that were far from favourable. IZOLYATSIA was lucky enough to have developed its own way, independent of political and state art establishment, in Donetsk as in Ukraine. But because of this, we were considered a threat by the regime in power. Contemporary culture, free thought and participatory activities may have a dramatic impact on local communities, helping develop critical thinking, and this was clearly out of the political agenda in Ukraine.

An important aspect of IZOLYATSIA's work has always been its educational projects. In the cultural vacuum that dominated Donetsk, we felt an urgent need for professionals in the field of arts: not only artists, but also critics, journalists, art production specialists, and so on. We realised that the only way to bridge this gap was to educate young people in the region. This is why we invited young and acclaimed Ukrainian artists, authors and designers for the Switch On! programme. At their lectures and masterclasses for the Donetsk youth, they shared their knowledge, skills, but even more importantly, they gave a sense of perspective, showing teenagers that there are many ways of achieving success in the cultural field. It is my firm belief that, if many projects like this one had been carried out throughout Ukraine and financed by the State instead of one private initiative, the catastrophe in the Donbas would have never happened. But sadly, all our followers, the next generation of Donetsk, left the region just like us.

SBWhat was it like when you learned of the impending threat on the foundation when the separatists occupied the factory while you were away in Kyiv in 2014? It is said you knew it would happen, but you didn't know how painful it would be when the separatists occupied the factory. What do you recall of those events?

LMAfter the seizure of our premises by the militia of the so-called 'Donetsk People's Republic' in June 2014, we have gone through a full scale of emotions, from hate to disgust to indifference. We also couldn't quite understand the actions of the Ukrainian government at the time. Since early 2014, we were aware of the processes going on in Eastern Ukraine: the so-called 'Donetsk People's Republic' wasn't born out of the blue after Euromaidan—it was a project long premeditated and prepared for by Russian intelligence. We saw people with DPR flags in Donetsk one year before the events—some of them trying to interrupt the TechCamp Donetsk 2.0 [workshop] we organised with the support of the US Embassy. But we could not do much ourselves to resist this without State institutions, which did not work at all at that moment.

As we headed for Kyiv in June 2014, we realised that it would be impossible to continue making projects with tanks invading Donetsk. But even in our darkest nightmares we could not imagine that IZOLYATSIA would be devastated and turned into a prison ... We all felt utterly disgusted, as if we had been raped. The most disgusting part was to discover how the fighters looted the premises, stealing anything valuable, up to the most basic things. It became quite clear for us that they didn't even understand where they were, and didn't understand the value of the artworks housed at IZOLYATSIA. It was all alien and detestable to them. Later, when we heard the news about the destruction of many of these works, it wasn't as painful as that first feeling.

Thankfully, we have overcome the hatred. In that raped body, we managed to save the spirit and a great team. After the exile, IZOLYATSIA's mission was to tell our story to the world, so we focused on launching discussions in Ukraine and abroad. Our information exhibition Culture and Conflict: IZOLYATSIA in Exile, speaking about the events in Donetsk from both our and 'DPR''s perspective, was shown at the Palais de Tokyo, DOX (Prague) and Heinrich Böll Foundation in Berlin. The guerrilla campaign #onvacation during the 56th Venice Biennale was a loud statement about the occupation in Ukraine. Our most recent exhibitions, Blue Sky Catastrophe at the Villa Arson and Architecture Ukraine – Beyond the Front at the Biennale Architettura 2016 in Venice, also reflect on the Donbas events within the global context.

In Eastern Ukraine, we are carrying a series of initiatives known as Zmina, consisting of street art projects, film screenings, public talks and presentations, lectures and workshops. All these are aimed at activating local communities and becoming a catalyst for social awareness of the population. In October 2015, during the mayoral elections in Mariupol, we launched the Letters to the Mayor project, in collaboration with Storefront for Art and Architecture (NYC). A selected group of architects and designers was invited to write a letter to the Mayor of the city of Mariupol, articulating some of the pressing concerns and desires that, as an architect, they believe play an important role in transforming the city. These letters were later exhibited and, complimented with letters from ordinary citizens of Mariupol, sent to candidates in the elections.

SBSince establishing IZOLYATSIA in an industrial neighbourhood in Kyiv not unlike that in Donetsk, how has the mission of IZOLYATSIA as a whole changed with its current experience as a foundation in exile?

LMOur mission has remained the same: inspiring positive change in Ukraine by using culture as a tool. As a platform, we try to create opportunities and give maximum creative freedom to aspiring artists. As a foundation, we act both locally, most importantly in Eastern Ukraine, and globally, through our international projects.

SBIZOLYATSIA's programme is multi-faceted, and includes workshops with various international institutions, as well as exhibitions and other endeavours. Could you talk about the ideas behind the different components that make up the foundation's activity today?

LMSince the beginning, IZOLYATSIA has had three intertwined directions of activity: art, education and projects geared at activating Ukraine's creative sector. Our art projects are usually based around the one topic each year. In 2015, the main theme was, obviously, 'Occupation'; in 2016, it is 'Borders and Memory'. Another important subject is the public space: both our Kyiv exhibitions and projects in Eastern Ukraine question the use of public space in the post-Soviet reality, as it transforms from a 'meeting place of authorities with the people' into a more open field of social interactions. This is well illustrated by our most recent project, Social Contract. Consisting of an exhibition featuring works by eleven artists from ten countries, a public programme, and a temporary art intervention Inhabiting Shadows by Cynthia Gutierrez at the former site of the Lenin monument in Kyiv, this project questions such burning issues as commemoration, commemorative objects and public space.

Our education projects, some of which I mentioned above, are aimed at giving rise to a new generation of professionals in the cultural field in Ukraine through workshops, artist talks, residencies, etc. We realise that these professionals will need an infrastructure that is not always to be found in Ukraine where the State gives no real support to culture. That is why we created IZONE, a hub centre devoted to championing emerging talent in contemporary practice set within the context of the arts, creative industries and technology. The IZONE creative community includes spaces for temporary exhibitions, concerts and lectures, IZOLAB (the first fabrication laboratory in Ukraine), photo studio, several workshops, café and a bar. We believe that creative industries are a new hope for the Ukrainian economy. It's also critically important for us to show young people in Ukraine that it is possible to make a career in the arts.

SBIt seems there is an emphasis on reaching out beyond Ukraine and exploring various cultural, historical and political connections, such as those between Albania, Turkey, Greece and Ukraine, as exemplified in The Presence of Absence, or the Catastrophe Theory, a recent exhibition curated by Cathryn Drake and staged at the foundation. Featuring artists Ali Kazma, Petros Efstathiadis, and Leonard Qylafi, the project explored the connections between a post-Ottoman, post-Soviet past, against the foreground of a world in crisis. Then there are educational exchange programmes, in which you have collaborated with such institutions as AS220 from Providence, Rhode Island, which privilege active knowledge production and exchange, as well as developing projects abroad as an institution in exile.

How would you describe the intentions behind these projects, and how do they reflect IZOLYATSIA's ethos as an institution operating within the context of Ukraine today?

LMWe don't want Ukraine to be isolated, which is why we try to bring international artists here, while showing Ukraine to the world with our exhibitions. We want to show that the history of Ukraine, its present and future are inseparable from Europe and the world. It is important for us to share the experience of other countries, because Ukrainians are far too often preoccupied with their own problems, refusing to look around. Ukraine needs a global perspective badly. We want to make it possible for young people to get this perspective without having to leave Ukraine, therefore we favour projects bringing professionals here. But exchange is vital as well, so of course, we also have artist-in-residency programmes in collaboration with several European institutions, allowing aspiring talents in Ukraine to make their research abroad and inviting foreign artists to Ukraine.

SBHow did you come into your relationship with art? In other words, why is it that you do what you do?

LMI was born and raised in an industrialist's family, in a highly industrialised city in USSR, where I couldn't even dream of making art a career. Even though I have always loved art history and read a lot, I didn't really have much choice in terms of a professional path: it was bound to be industry. I made a business career in industry, but culture has always remained my hobby: I have been collecting art for many years. I also travelled a lot and saw multiple manifestations of contemporary culture that inspired me to make something similar in Ukraine.

When I founded IZOLYATSIA in 2010, it was my homage to the people of Donetsk and an attempt to give them opportunities that I didn't have in my youth. I wanted to turn my hobby into a career and make it possible for other Ukrainians to do the same. —[O]