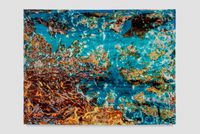

Mark Bradford

© Mark Bradford. Courtesy of the artist

© Mark Bradford. Courtesy of the artist

Born in Los Angeles in 1961, Mark Bradford creates paintings without paint. Earlier in his career he used street merchant posters and hair salon end papers, sticking them to canvases and then tearing them away and sanding them down. The resulting works are abstracts imbued with subtle traces of cultural specificities.

Having won the MacArthur Foundation Award in 2009, and received the US Department of State's Medal of Arts earlier this year, he is also an important public artist. His sculptures include an ark he made in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, and a wooden Jumbotron he installed at LAX. The latter's commentary on surveillance is a real coup, a work that seems far too wry to have been approved for such a humourless environs.

Outside America, Bradford is currently showing at the Sharjah Biennial (until 5 June 2015), and is in the midst of his first solo show in China, Tears of a Tree. Curated by Clara Kim, the show is taking place at the Rockbund Art Museum, Shanghai until 3 May 2015.

In putting together this exhibition you searched Shanghai for raw materials to use—paper posters, fliers, etc—but couldn't find much. The antique maps you used as a reference were, I imagine, new prints, perhaps made to look old, but ersatz. This obstacle to your usual process says something about Shanghai's erasure of its past, with paper materials destroyed, hidden or replaced by plastics, and censorship of its present, where posting bills and graffiti and other forms of public expression are limited. Was it important to you to tell the story of not finding materials to work with here?

The social context in which I make my work—including the story of the materials, which are not scavenged or found—is all part of a larger picture, which fundamentally drives my practice. In terms of the actual creation of my artwork, those gaps are not so important. There are a number of materials used to create my art. However, the exact history and historical value of my materials is not so essential, even though those factors do reveal something about the context or landscape from which a work is made.

The Loop of Deep Waters—eight paper buoys commissioned for the show—was inspired by the Huangpu River. You've said that waterways constitute historic infrastructure, older than any airport, highway or cargo crane. Why was Shanghai's history such a focus for your show, when there is so much talk about its present and its future?

In researching my Rockbund show, I spent time walking around the historical neighbourhoods and walking along the river. I was inspired by Shanghai's rich past and by its visual beauty—especially, in the way that this thriving 21st century city surges forth on the historical patchwork of traditional Shanghai.

Your works appear grounded in ethnographic exploration, and are often somewhat representational—from the glimpses of the source materials' original images to the clear grid of the map in Falling Horses, to the forms of the Jumbotron and Ark in your public works. Are you really an abstract artist?

In my mind I am an abstract painter, but I mine the framework and ideologies of painting's history. I have never believed that abstract painting can exist independent of its social context or history. Making abstract painting within a social context has always been a primary concern of my studio practice.

In the conversation with Clara Kim at Rockbund you talked about wanting to be an abstract artist because you didn't see other black abstract artists around you. Are their still expectations that people from certain ethnic groups make certain kinds of art?

That has been changing, thank god. —[O]