Martin Creed

The first time I ever saw Martin Creed in person was at the epic Gavin Brown and Herald St party at Art Basel Miami Beach in 2014, at which Creed was the opening act for the amazing Yo Majesty and legendary 2 Live Crew. Creed’s performance was short, sweet and bitter: it consisted of the artist strumming a banjo and repeating the phrase “fuck off” in various rhythmic arrangements. (“Fuck-fuck-fuck-fuck off” being one.) This was either a memorable intervention in an absurd setting, or an articulation of the general feeling about the Art Basel Miami Beach circus. The beauty of the performance was in the ambiguity—a cathartic double play in which we appeared to be both mocked and embraced for a certain kind of shared guilt and complicity.

The performance came immediately to mind when I visited Creed’s website. Upon first opening the site, and before scrolling through the artist’s catalogue of works (all numbered, none titled), I was presented with a video featuring flashing images of border checkpoints to a soundtrack of Creed singing “Border Control” over and over. Like the Miami performance, it struck me how directly Creed can issue a slap in the face with the most crude—and endearing—of actions. At the same time, the video also recalled the exhibition Creed just opened in August at Hauser & Wirth Zürich, which included the word ‘REFUGEES’ spray-painted on to the gallery’s window in black alongside paintings and sculpture.

Of course, Creed is an artist who is difficult to pin down, especially when it comes to thinking about what exactly ties his practice together. This was evident in his recent survey exhibition What’s the point of it?

at the Hayward Gallery in London that brought together works from over two and a half decades (including Blu-Tack on a wall, Work No. 79 to 1,000 prints made with broccoli, Work No. 1000). Taking his new show at Michael Lett in Auckland as a launching off point and drawing on the recent work presented at Hauser & Wirth, Ocula spoke to Creed about what his practice means.

Let’s start with your upcoming show at Michael Lett—what will you be showing?

Well, it’s actually when I get there that I will finish the show, because I’m planning to make one large painting in Auckland just in the few days before the show opens; I’ve planned that, although I don’t know how that’s going to turn out. But that’s one element of the show, basically; a kind of improvised work just before the opening. Then I have some metal beam sculptures, which are being made in New Zealand, which are all kind of like families of metal I-beams—the kind that are used in construction. So there are all these elements that I’m going to work out when I get there. I don’t want to plan things too much, but of course at the same time, one has to plan things, too.

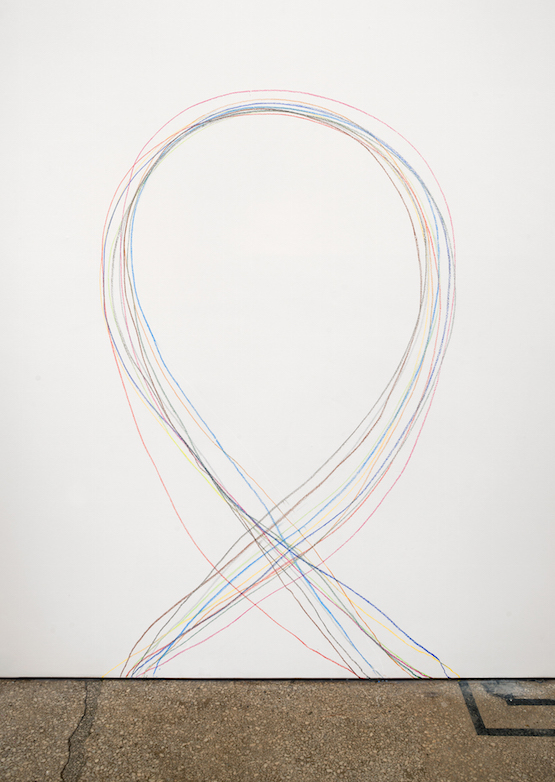

Exhibition view, Martin Creed, 2015, at Michael Lett, Auckland. Image courtesy Michael Lett

The use of I-beams reminds me of Chris Burden, somehow, and his post minimalist sculpture, and this in turn makes me think about your Hauser & Wirth Zürich exhibition, which runs to 31 October. In the show, you have a series of works that allude to minimalism, works that revolve around stripes: from gesso stripes painted on fabric, to wooden strips joined to form a square, and then treated with various varnishes. But what’s interesting about this exhibition in Zürich is that it also seems to revolve around this spray-painted ‘REFUGEES’ sign that you wrote on the gallery’s window.

What (if any) is the relationship between the context of the white cube, your apparently minimalist work and then the sign, ‘REFUGEES’? And then what is the relationship between the works presented at Hauser & Wirth versus what you will be showing in Auckland?

Well, to me, it’s all connected somehow; every show is. I’m just trying to do my best in the world with working. It’s a difficult thing. For example, I think that some of the works might look like what is known as minimalism, but I don’t really try to make them like that. It’s just that most of the time I feel like I’m trying to get back to basics, you know, and so you end up with what you would call minimalist works.

But then it’s the same with the spray-painted REFUGEES sign; that’s kind of the same thing, because I feel like all the time I’m just basically thinking: “What the fuck am I doing? What am I doing?” I think, god, I’m living my pissy little life, and people are dying trying to have a basic life, you know?

I think I probably feel a bit guilty—it’s like I’ve got all this space; I’ve got a show; I’ve got this large room, or whatever, to express myself in. So these kinds of thoughts are whizzing around in my head while I’m thinking about all these different works and shows.

I certainly don’t feel like I know what I’m doing, but to me that’s the danger of talking about it as we’re doing now. The danger to me is that if you’re talking about something it can often sound as if you know what you’re doing.

Exhibition view, Martin Creed, 2015, at Hauser & Wirth, Zürich. © Martin Creed. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth London

Thinking about these guilty thoughts you have in relation to the issues of the present moment, it’s interesting that the first thing we see on your website right now is this video work, Border Control. The piece made me think about something you said once: that you want your work to have the whole world in it, and Border Control really invokes that. Yet, funnily enough, the editing, which splices a whole load of images together, is evocative of those striped works in Zürich, which present different materials and stripes within a minimal frame. This reminds me of what you said once about the combination of a painting and a viewer constituting a live event.

Well, I suppose the thing that comes to mind immediately after hearing what you just said is life, as I feel it, is a kind of big soup, and it’s ever changing. So nothing is ever fixed, or in other words, everything is live. You know, we can say that a painting is fixed but because of you—the person looking at the painting—it is not fixed, and it’s moving and breathing, [and therefore] the experience of looking at the painting is definitely not fixed. So if you follow that logic, everything is a live event and I feel like I must work on everything in light of that. In other words, a painting or any kind of “fixed” work, like an arrangement of colours on a canvas, or some metal beams or whatever—anything you might say is fixed—must be worked on because it’s actually not fixed. So it’s like you cannot separate the painting from the wall, just as much as you cannot separate the work from the viewer.

Martin Creed, Work No. 2574, 2015. Bricks, 59 x 21 x 22.5 cm / 23 1/4 x 8 1/4 x 8 1/2 in. Image courtesy Michael Lett

I’d like to stick with this idea of things not being fixed, because this relates to the fact that your works are all titled in numbers, which turns your portfolio into an expanding inventory with no real conceptual clue offered in any title. This creates a kind of non-hierarchy amongst your works, since things are essentially categorised in the sequence that they were made. Thus, there’s no difference, let’s say, between Work No. 1020—‘an evening of talk, song and dance’—or your Turner Prize work, Work No. 227: The lights going on and off.

In thinking about the numbering of your pieces, is there a reason why you’ve numbered your works as if each is simply part of an ongoing database?

It originally started from feeling that I did not want to have titles; the numbers were a way of taking away the need for that. I remember at the time I started doing this there were a lot of works called Untitled, and I didn’t like that either, but I wanted a way of keeping everything the same, you know. I think the thing about it is that trying to make a work always feels like you’re trying to fix something; you’re trying to fix something in the world, and that always feels very artificial to me. It always feels terrible to do that, because it’s not like life at all. So the idea of a title feels brutal to me—like making cuts in the world to separate one thing off from another.

To me, that’s how I feel about borders, because basically, when making a work you have to draw a line around something effectively. And in a world that’s a continuous blobby mass that is a very, very artificial and inhuman thing to do. It’s not human to separate things out, I feel, because it’s all a big cohesion. I feel like trying to draw a line is always going to go badly: you end up with terribly artificial borders. I would like to make a work that doesn’t draw lines, and doesn’t separate people, places, and things. As I said, a work that has the whole world in it. It seems like that’s an impossible task, but I feel like you can have a microcosm of the world in a work, you know?

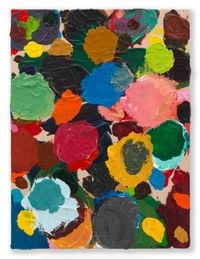

Martin Creed, Work No. 2166, 2015. Acrylic on canvas, 40.5 x 50.5 x 2.8 cm / 16 x 19 7/8 x 1 1/8 in. Photo: Pedro Martinez de Albornoz. © Martin Creed. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth London

This idea of blurred boundaries is interesting. Your website is called “the official and unofficial website of Martin Creed” and then there is your work with the words “Here and Elsewhere”; in both, the word ‘and’ connects and divides but does not separate, somehow. This relates to your practice as a kind of wrangling with these ideas of chaos and contingency in the world.

But I feel like this also relates to order—you have said that order is a comfort for you, but something that you do try to overcome in your practice. I’m curious about this when thinking about this ordering of your works through numbers to evade a fixed framework. The recent exhibition at the Hayward perhaps gave you the opportunity to look back on this extensive list of numbers, which speaks to your ongoing practice. Does a certain order emerge to your mind?

Well, I’m not really happy when I look back; I feel like I was just barking up the wrong tree. I just feel like a deluded fool, like I’m always struggling, but I do like some of the things I’ve done. You know, I’m talking about things being a continuous mass but I also feel like I’m always trying to control things because if it’s just chaos, it’s just a nightmare! So when I look back, I suppose it’s weird. Like when I think about the Hayward show, which was probably the biggest show I’ve ever done, I was surprised that many of the older works on display seemed really, really clean since my memory of them was really dirty.

You know, I always feel like I’m working with my own shit, and that’s what all my work is: stuff that comes out of me. And maybe I’m disgusted by it a lot of the time, and maybe there’s a feeling of guilt as well—of me just twiddling around with my own stuff. So when I came to look back at some of my earlier work at the Hayward show, I was surprised that they didn’t seem shitty the way I remembered them. It actually didn’t seem like my work at all, because I’d lived with them in my bedroom in the years after art school when I just lived in a wee room and made my work in there. When I saw them on the wall of the Hayward Gallery twenty years later, it didn’t seem like the same work. They felt like exact copies someone had made, with all the dirt cleaned off. That was a weird experience.

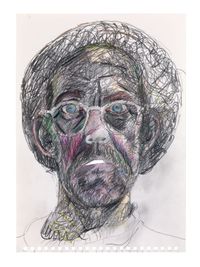

Martin Creed, Work No. 2575, 2015. 2 synchronized videos; HD digital, black & white, silent 2 min 7 sec, looped. Edition of 3 + 1 artist proof. Image courtesy Michael Lett

On the title of your Hayward show, What’s the point of it? you said this was question you often ask yourself. I wonder how your approach to this question has changed since you first went into art? What is the point of it all for you now?

When I was trying to decide what to do at university, I had a few things in mind—I was maybe going to study English or psychology—but in the end I think I did art because all the other subjects seemed too narrow. It seemed to me that the field of fine art allowed you to kind of do anything since it contained all the other things I was interested in, and I still think of the art world this way, basically. Because everything that everyone does is art: a form of expression, a creation. In other words, literature, writing, work, a job, riding a train, or whatever, is a form of art, as is psychology and architecture and music, since these are all forms of creative expression.

I don’t know if these thoughts were going through my mind when I was sixteen, but I was definitely thinking that if I did fine arts, I could still study the other things, more than if I did English literature. When I was learning about art growing up, reading those children’s books, it seemed to me that artists did everything: it was all mixed up together—art, writing, music, theatre and dance, whatever.

Martin Creed, Work No. 2329, 2015. Imitation wood grain , 215.8 x 216.4 x 7 cm / 85 x 85 1/4 x 2 3/4 in. Photo: Alex Delfanne. © Martin Creed. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth London

This relates to something you said in a Guardian interview: “Anything is art that is used as art by people.”

I don’t really like using the word ‘art’ particularly, because I feel like it’s not a clearly defined word, and I don’t really know what art is. What would be considered “art” would have to be anything that is called art collectively by a certain number of people who like a certain thing. This is like a collective build up, because then this liked thing might end up in an art gallery or something like that. But to me, in a way, I feel like the question of what’s art and what’s not art is basically a side issue because that’s just the definition. The real question is how to live: how can you live your life and live with yourself, basically. That’s the real question. That’s what I’m trying to do with my work: I’m trying to live with myself.

Martin Creed, Work No. 2562, 2015. Oil pastel on wall. Dimensions variable. Image courtesy Michael Lett

That leads on really nicely to my next question, which I love to ask artists: if there is any advice or wisdom you would give to kids today who want to engage in the arts, what would it be?

Well, I would say: do what you’re scared of. Because I feel like often what you’re scared of is often what you really want to do, from my experience. And another thing I would say is: don’t trust yourself—because I think the biggest fight is with yourself, not with other people. It’s easy to see this if someone else is trying to get you to do something you don’t want to do; usually that’s relatively easy to see and deal with. But when you yourself are trying to get yourself to do something you don’t want to do, it’s much more difficult to understand that.

Often the biggest thing that is difficult to resist is the tendency to always take the path of least resistance, and I feel like we do that without even realising we are doing it. All it takes is just a few little turns on the road and before you know it you end up sitting on the sofa watching TV, which is fine if you want a quiet life, but then it’s a kind of boring life, too, when you really get down to it. The excitement of life is much more dangerous.

Which brings us back to your show at Michael Lett, and what we talked about earlier: this idea that your practice is about engaging with the world in an immediate and contingent way.

Aye, that’s how you could argue it in a way that I would understand. —[O]