Sam Falls on Nature's Imprints

Sam Falls. Photo: Ed Mumford.

Sam Falls. Photo: Ed Mumford.

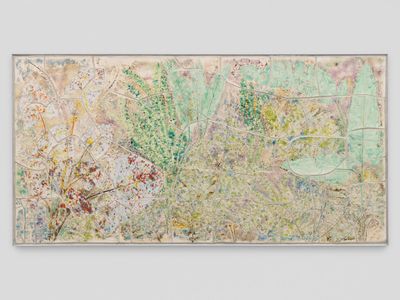

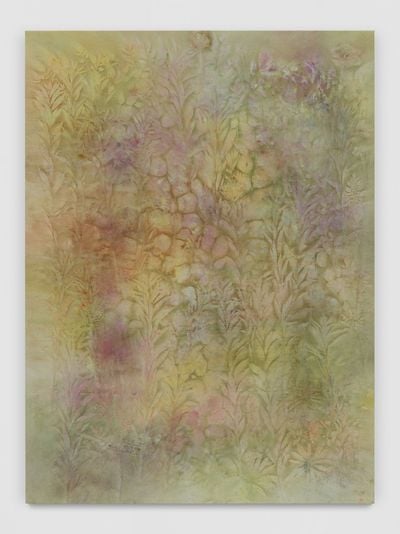

Expanding the notion of landscape beyond the canvas, artist Sam Falls is not merely inspired by nature, but works directly with its elements. Devising processes that uptake the imprints of all atmospheric conditions—from sunlight to heavy rain, Sierra Mountain winds, and morning dew—Falls conceives abstract paintings, prints, and ceramics that conceal traces of plant-life and memories of place.

Falls' latest exhibition at Galerie Eva Presenhuber in Zurich begins with the idea of duration and cycles of growth and decay to urge a renewed ecological conscience—something that has become more important to the artist who feels the impact of climate change strongly from his part-time studio in California, where droughts and forest fires abound.

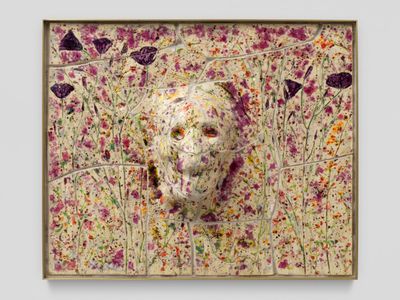

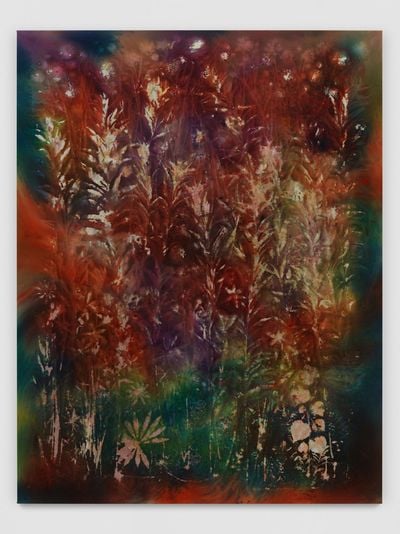

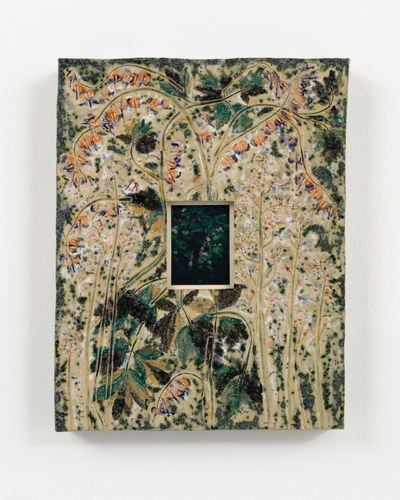

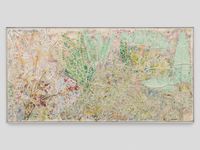

Works on view include the artist's classic sun-dyed paintings, which layer different vegetal forms above the canvas outdoors and take up to a year to set, new prints made with natural dyes conceived on his farm in Upstate New York, and delicate ceramic surfaces housing plants, skulls, and self-developing photographic images.

Growing up on a small farm in Vermont, Sam Falls excelled at mathematics, which pushed him to pursue a career in the sciences rather than art. He attended Reed College in Portland, where he studied physics and encountered philosophy, which led him to semiotics and eventually the visual arts.

'What really piqued my interest is that you could take things that seemed like objective realities to everyone and mess with them to create alternative meanings,' the artist says. His early photo-related influences include artists Liz Deschenes, Walead Beshty, and James Welling, who experimented with abstract photography.

'I remember thinking that if I kept pursuing theoretical physics, I would be getting further and further away from tangible reality,' he explains. Attending openings and talking about art felt more purposeful, which he would acknowledge, later opting out of science to study photography at ICP-Bard in New York City, where artists Nayland Blake and Moyra Davey taught.

Falls was still in graduate school when digital photography became trendy, which he found limited and one-dimensional. He sought ways to engage art in relation to the world beyond the art microcosm. To open his mind, he got rid of his camera and started experimenting with image-making outside, placing objects on a readymade or dyed fabric under the sun, which left behind abstract marks.

This preference for the analogue and essentiality is noted in his latest ceramic pieces, which incorporate photography but only in the obsolete medium of Fuji film instant image. In this conversation, Sam Falls speaks with Paul Laster, discussing early influences, processes of making work in the natural environment, and literary influences on his work.

PLWhat are some of your most successful works that utilised placing an object on a readymade or dyed fabric and leaving it out in the sun?

SFI would definitely say some of my first ones. When I moved to California, I would walk around and collect abandoned tyres because I knew I needed something that would hold its form over a year or two. I also wanted something that would make an abstract mark.

These tyres represented the place I inhabited. They had a land art site-specificity, which I was always influenced by. And then, there was this element of abstract painting and the history of more contemporary modern painting, like Barnett Newman zips or something where you have a repetitive abstract mark that gathers meaning. In the finished artwork, the form of the tyre creates a circle, which is a perfect abstraction, but you also recognise it as a tyre. It has this photographic element of how it was made with light, but it also looks like a painting because it's on dyed fabric.

PLDid you conceive these abstract representations of objects from your immediate environment to be perceived as a form of minimalism?

SFYes, it was about narrowing the work down to the place it was made and the time it took to make it and how that could connect to a viewer. I didn't want superfluous gestures that would point back to me.

PLHow did you shift from making sun-faded works with found objects to making paintings of plant life with pigments and precipitation?

SFWe had moved from Los Angeles to nearby Topanga, which is more rural, so I could work with the sunlight. During the winter, it started raining and I had anxiety about how to make work.

I remembered having a big conversation about the state of photography around 2010, where we had talked about Wade Guyton using the inkjet printer and the kind of scale he achieved while still making this gestural abstract work. Different things combined to make me think about using rain almost like a printing process.

The idea of removing my hand has always been important to me . . . With the patina changing, you see time passing—you see nature's take on the work.

It's either super sunny in California or raining hard, there's not much in between. I thought it was something I could harness to make a representation of the moment. I put wood from our yard on terry cloth sprinkled with pigments and let it set in the rain to make a painterly impression. I wanted the substrate to be relative to the subject.

After that experiment, I was visiting my mom on the farm where I was raised in Vermont when I had an upcoming show. There was no way to make work there, so I repeated the process with ferns from the property, which really represented that place.

I continued doing the sun-dyed works, but those take at least a year, even in L.A. So, while those are baking, I could have this other way of working. That led us to get a place in Upstate New York and become bi-coastal. I work with the rain in New York in the summer and the sun throughout the year in L.A.

PLHow do you see these works in relation to Yves Klein using bodies to apply paint to canvas, or Jackson Pollock dripping paint on canvas, where he similarly worked with the canvas on the ground?

SFI love those works. Over the years, those references have been true to the work, but were not really a catalyst for it. I do work like Pollock, with the canvas on the ground, which leads to scale when working outside. You're surrounded by land instead of the four walls of a studio, so the scale becomes more relative to the body and nature. Klein did the body works, but also things like driving with one of his paintings on the roof of his car. So, getting outside the studio opens up the work to experimentation.

PLYes, Klein attached a pigmented canvas to the roof of his car and drove from Paris to Nice in the rain and Richard Serra let the rain patina his Corten steel sculpture, Modern Garden Arc (1986) in the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA)'s garden during his 1986 retrospective. Have you made works where the artist's hand is likewise removed?

SFThat's kind of my goal for all the works. The idea of removing my hand has always been important to me. It leaves room for viewers, just like seeing that sculpture change at MoMA. With the patina changing, you see time passing—you see nature's take on the work.

Some of my favourite works were made when I just left canvases out in the woods. The leaves fell and then I applied the pigment. So, the hand of nature created the composition.

PLAnd you did a similar piece with apple blossoms during an art residency in Finland, right?

SFExactly. I'm surprised you know about those works. I was working on pieces in a field and saw the apple blossoms bloom and then start to fall. I laid the canvases under the trees and left them for a week while the blossoms fell. Then I put the pigment on and left it for another week while the weather accumulated and catalysed the dyes.

PLWhat was the overall effect? Did it look like a Pollock painting, with all-over action?

SFIt looked like something I had been trying to achieve. It was both happenstance and natural. You can't do much better than nature. The blossoms looked wind-swept, which was perfect, because the wind had blown them off and back on again.

PLWhat led you to add ceramics embedded with plants to your body of work?

SFIt was similar to how I started working with the rain. I had no classic art training before I went to graduate school, only an interest in photography. My agenda is more conceptual.

My wife Erin creates ceramics, and her first big kiln was in our shared studio in Upstate New York. I began experimenting without it being part of my practice. Then I figured out a way to work with nature and local clay, which was important to me.

Ceramics became another means of making a testament to nature. It offered a way to fossilise the plants that bloomed in spring and withered throughout summer and fall. It was our first house and garden, so I got attached to the flowers. I watched them bloom and then had this new anxiety of watching them die.

PLAre you familiar with John Cage's Medicine Drawings (1991), in which he embedded medicinal herbs into handmade paper?

SFI do know those works, and I also have this great book about his mushroom works, A Mycological Foray (2020). The more I work with nature, the more I find it hard to believe that it's not a part of everyone's work.

PLWhen I first wrote about your work—through reviewing your show at 303 Gallery in 2018—you were making large-scale paintings about a place, the way an Ansel Adams photograph would capture the essence of a site in nature, but by bringing a sense of the whole forest onto the canvas. How did you pick the sites, make the works in situ, and what were you hoping to convey about the place?

SFI did a project for LA><Art in 2013 where I went to every national park in California and installed a wind chime. I worked with a chimer and made the chimes out of raw copper and steel. They all sounded the same in the beginning, but oxidised differently, depending on their geolocation, and sounded different in the end.

For the painting you mentioned, I was working with [curator] Anne Ellegood at Hammer Museum on a project for their lobby. The idea was to use that element of site-specificity in my work and go to different national forests and make a painting in each one.

By then I had learned how to make one of these paintings in most weather conditions. In a dry climate, the morning dew would be very light, so the paintings would be more speckled or almost pointillist. If there was heavy rain, the colours would bleed. I knew they would convey different feelings, especially with different plants, depending on the environment. From there, the landscape form developed, by going to different places and using multiple species.

If land art was a sort of manifest destiny . . . then painting and photography is renting an apartment in a city. What I'm doing is more like camping.

We had just had our first baby during that winter, when it was especially wet in California. I knew I had to make the paintings, but I also had to help take care of the baby. Driving eight hours to a national forest, I didn't have time to go home and come back again. If it was really windy, the plants would blow off, so I would just do another layer. That was when I started doing multiple exposures and using different elements, like fallen trees. They would hold the canvas down and keep the plants in place. The works then got more dimensional and more layered.

PLIn past conversations, you've mentioned the influence of Robert Smithson and his 'Site/Non-site' works on your process. Was this a juncture where your work went from being related to minimalist abstraction to maximalist land art?

SFThat's a great question. I have said that if land art was a sort of manifest destiny—especially for artists like Michael Heizer or Donald Judd of taking over raw nature—then painting and photography is renting an apartment in a city. What I'm doing is more like camping.

And I think that's what the 'Site/Non-site' works were—going to a place, experiencing it, being inspired by it, and making the work there, but leaving no trace, like camping.

Smithson did both. He did Spiral Jetty (1970) on site. He made his impact, but he also did these 'Non-site' works, where he would have material from the place. I wanted to do something in between, where I left nature preserved but the work also was created there.

To me, the paintings are still more minimalist, but because of the nature of how they're made, they've become very colourful, which looks maximalist. But I don't like maximalism.

PLAre you also commenting on the environment and need to protect it in these works?

SFAbsolutely. It's something that's grown in my work, my agenda, and practice as I've continued to work with nature. It's also become such a hypercritical issue. Living in L.A. made that apparent to me. You're conscious of water usage, forest fires and pollution. These issues kind of pinnacled at the time I did that Hammer [Museum] project going to national forests, and we had just had our first kid.

I made those paintings right before the Woolsey Fire in California. My wife tried to reach me saying, 'You're where the fire is.' That was both enlightening and scary. But like I was saying about the ceramics as fossilised remnants of plants, the paintings were made a week before that area of forest burned down. Those plants were destroyed and the works captured this place that was forever changed, or at least for a while. The environment became more of an issue for me and the work.

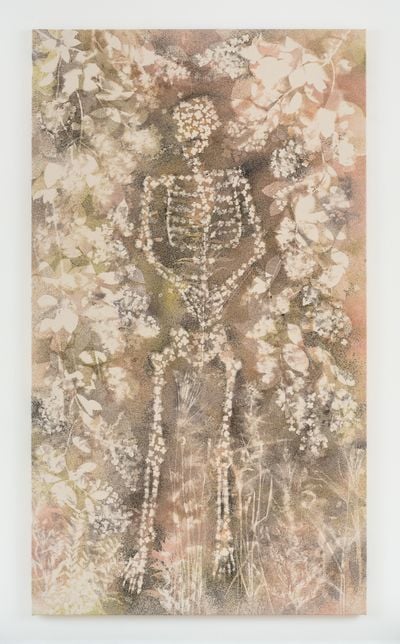

PLDuring the pandemic, you started making works that brought the figure into your work through the creation of corporal forms with floral petals and sticks in the paintings and by covering skeletal bones with clay to recreate their shapes. What motivated you to make this shift at that time?

SFIt was at the beginning of Covid-19 lockdown. I was at home with our limited space and gardens, so the works got smaller. I was also surrounded by my family and this kind of emotional content entered the work through the figure.

I had always been looking at books about naturalism and symbolism of plants in painting. I had been ignoring the figure while looking at these masterpieces, but then began reading about how figurative symbolism was such a big part of these works—and not just iconography and religious paintings of the Renaissance, but also for French Symbolism and all the way through Matisse. That became really inspiring. So I used my family as the figures in my work and posed them to represent different emotional states.

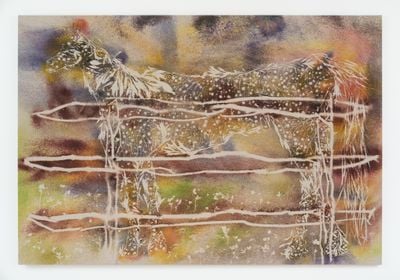

PLYou introduced glass into your body of work by casting fences in coloured glass in your recent solos at Jessica Silverman Gallery in San Francisco and 303 Gallery in New York. What were you trying to convey in this new sculptural work?

SFConceptually, I was trying to convey something about boundaries and borders: the lines we cut between nature and domestic space or wildness and domestic space, the landscape and civilised space, but also these issues of borders between nations and property lines.

I specifically used a split-rail fence, which to me represented farmland. On the farm where I grew up, my mom had horses and I grew up putting those fences in and maintaining them and some had old carvings in them.

I carved naturalist lines from poems or songs into these fences from our farm in Upstate New York and cast them in glass. The glass represented this kind of fragility in a sculptural material that, of course, becomes solid when cast. The coloured glass captures light. It's meant as an outdoor sculpture, so it changes through the day.

I had started using glass prior to that in the ceramics. The glass melts at the same temperature as the glazes, so I've been using it in the kiln as another natural material for my practice.

PLFor some years now, you've incorporated photography into your shows, but in new and inventive ways such as digitally printing your pictures on book leaves with pigments, or framing Fuji instant imagery photos of flowers with ceramic wall-work embedded with the same floral source. Do you see a relationship between these pieces and Henry Fox Talbot's experimentation the medium?

SFTalbot's work is something that I've always looked to. Even when working with the ferns for my first paintings, there was something about that connection I always wanted to wink at. Ferns are one of those prehistoric plants that have such a trajectory through representation.

It's kind of an added bonus with the photography and this idea of the Fuji film, a dying medium. For that specific medium, which is obsolete already, I think there is a real reference there. It's something I'm trying to highlight in contemporary art.

PLYou recently introduced embroidery into your work in your survey show at Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland (2023) and a solo presentation at Dries Van Noten's Little House in Los Angeles (2023). How are you using this medium—on what materials and to what result?

SFThose pieces are embroidered with idioms or mottos from ancient sundials on airbags that I collected from crashed cars in junkyards outside of Los Angeles. I started walking around junkyards in suburban wastelands and saw these airbags like blossoms of colour in the crashed cars. I cut them out and took them, then found out that it was illegal. But I got ten of them before I got in trouble.

I thought, how can I do something special with these? I noticed they're all different colours of nylon and have different embroidery on them—purple or red—and these human choices that were made in their making, or at least a human hand that went into it.

Parallel to that, I'd been reading this book about ancient sundials, with these melancholic phrases written in Latin and Italian—'use time', 'don't waste it', 'we are dust and shadow'—things like that.

My wife's mom was going through chemotherapy at the time, and she was really into embroidering. She didn't have much energy, so it was a nice way to collaborate. She'd always been very supportive and interested in the work, so she did the embroidery on the airbags.

So, these works have this discourse about life and death because the airbags are in crashed cars, but they're there to save a life. And my wife's mom, thankfully, is doing great. So, these are wonderful pieces for me. I made them a while ago, but did not have the right context for showing them until this year.

PLBoth the embroidery and the ceramic pieces with photographs and the impression of body parts are included in your current show at Galerie Eva Presenhuber in Zurich. What's the overall theme of this current exhibition?

SFAlong with the element of nature really growing in the work and the persistent idea of representing time passing, I've really focused on highlighting the existential element of time, which for me was always in the work. The faded sun works, for me, were almost like skins showing time passing.

There's this idea of growth and productivity, but also decay and disappearance. The colour sometimes got in the way of the more melancholic aspect of the work, so now I've been really focusing on that life-death juncture in the work.

There are the instant images with the ceramics, which are pictures of blossoming flowers. When they die off, I cut them and roll them in, so there's a more direct connection there. There are some figurative works in the ceramics, like a human skull that I made into ceramic with plants, and these arms that are like a skeleton gardening and this return to the earth, as well as the cycle of life.

There are new works, which you saw at 303, that are sun fades made with natural dyes. And while in the beginning of that type of work, I used things like tyres or two-by-fours that stood the test of time, I am now using live plants to make the image. They're outdoors for about eight months on these natural, dyed canvases and the plants wilt and wither as the sun fades. So you get a more ghostly image.

PLIs there something particularly new that you are experimenting with in this show, or are you revising these processes in different and perhaps more poetic ways?

SFThe Fuji film instant images are pretty new and the natural dye works are really new. Natural dye is something I've always been interested in, but I always thought it would connect more with the rain works. I couldn't figure it out because you have to use hot water to do the natural dyes.

Now, they're a way for me to meld the two processes. There's the dyeing element that I'm doing with plants, introducing my own dyes and then leaving them in the sunlight.

Although I primarily worked in national forests, and still do, I'm now making more work on the farm in Upstate New York. I can leave works outside and monitor them or have a closer relationship to them and follow the seasons and different types of weather more closely there. The rain paintings in New York are more durational than they've ever been.

PLWhat roles do literature and philosophy play in your overall body of work?

SFA big role; it's the main thing I do when I'm not making art. I read both fiction and nonfiction, and philosophy. I've never gotten over the argument of 19th-century aesthetics. There's so much to find that's relative to the work I make and relative to most artists' work.

The 303 show was really influenced by Cormac McCarthy. I always thought of him as a land artist. His work was maybe too masculine for me, but I liked it. It felt too assertive, but his most recent book, The Passenger (2022), was really based on physics and philosophy—right up my alley. I went back and reread all his books and found a sweetness and connection to the earth and America. Not necessarily a darker side, but the more melancholic relationship all people have with nature. —[O]