Tschabalala Self: 'We must abandon the lies and mistruths we have been told'

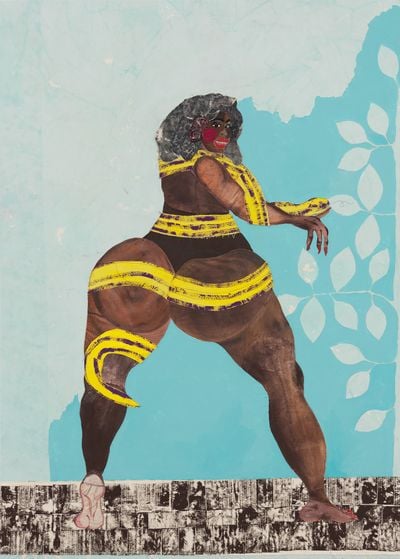

Tschabalala Self. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich / New York. Photo: Christian De Fonte.

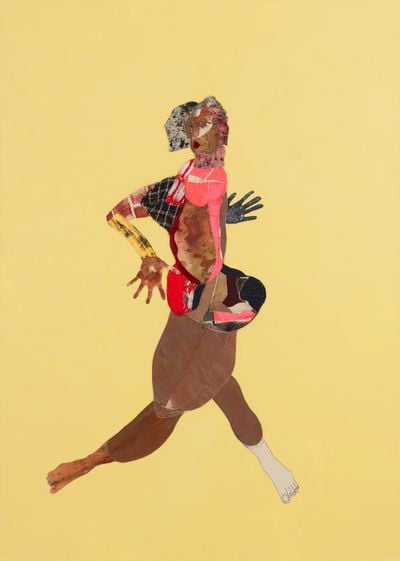

Tschabalala Self. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich / New York. Photo: Christian De Fonte.

Since graduating with an MFA from the Yale School of Art in 2015, Tschabalala Self has continued to develop a distinct approach to figurative painting, reimagining Black bodies as sites of multiplicity through sculptures and collages that incorporate drawing, textiles, paper, paint, and leftover debris from previous bodies of work.

Self's interest in reimaging the Black body as composed of a variety of shapes, sizes, colours, textures, and of different bodily configurations reclaims from art history depictions that have marginalised, caricatured, and overlooked such bodies, proposing instead a rethink that is celebratory, playful, and rooted in the nuances of Blackness drawn from both lived experience and Black popular culture.

According to the artist, her representations are not fictive, nor do they have enlarged or heightened features; instead, they are rooted in reality and frequently take cues from the body of the artist herself, whilst speaking to a wider politics of sexuality, race, gender, African-American histories, and Black futurity.

Take for instance her 'Bodega Run' (2017) series, which explores the iconography of New York City bodegas—Hispanic convenience stores that serve as important sites for encounters—whilst unpacking their social, cultural, political, and economic role in Black and Latino neighbourhoods through the products sold and the people who visit these spaces.

The project's fifth iteration at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles (2 February–9 June 2019) transformed the institution's white cube project space into a site-specific installation of a Self-styled bodega, boldly welcoming the viewer into a space filled with collaged paintings and a sculpture of a woman bent over mid-dance, backing the viewer with her buttocks on view, uncaring of any watching eyes.

Additionally, neon signage was hung in the space, whilst a surveillance mirror, a supermarket crate, wallpaper depicting popular products such as Goya Foods (the largest Hispanic-owned food company), and red, green, and black striped linoleum flooring completed the space's design.

Self demonstrates how the bodega operates as a site of cross-cultural exchange between black and brown communities including African Americans, African migrants, Yemeni, and Latino communities, whilst being intersectional and inclusive to the neighbourhoods it serves.

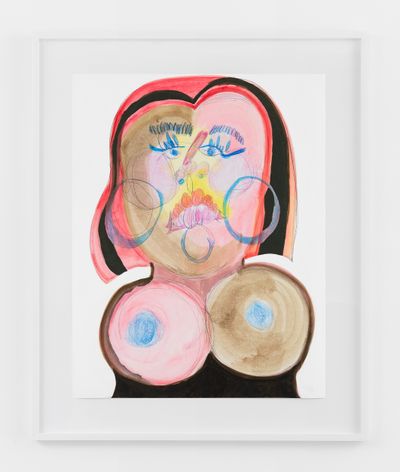

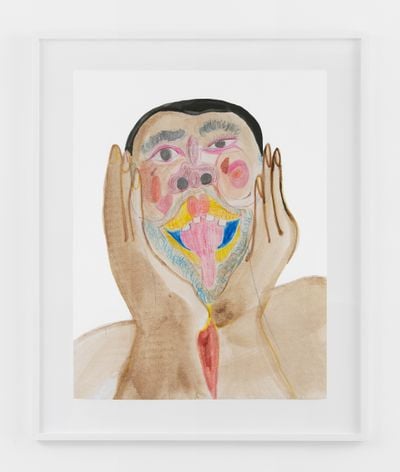

For her debut solo exhibition with Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Cotton Mouth, currently on view in New York City (7 November–19 December 2020) and featuring new paintings, drawings, sculpture, and an audio piece, Self turns her attention to mythmaking and its psychological and emotional resonance to Black life.

Drawing on cotton's symbolism as a textile that embodies American chattel slavery, Self also turns her attention to domesticity and bodily rage, considering often-unfair conflations between the latter and symbolisms in Western mythology.

In the diptych Carpet (2020), a female figure sits across from a male figure who is on his knees. Is he about to initiate something, or has she perhaps pulled away? As with Self's previous work, the viewer can make up a variety of conclusions. Also included in the exhibition is the artist's first audio work, titled Cotton Mouth, from which the exhibition takes its name—a monologue by the artist and a manifesto of sorts, which unpacks the narrative around Blackness, and how it shifts across time, histories, and geographies.

Through reconnecting with our true culture, I believe we can liberate ourselves in this present moment and fortify ourselves for the future.

In this conversation, Self discusses her process of collaging and weaving together new narratives of and for the Black body, in a practice that is intentional in its politics of unearthing truths whilst considering the importance of the diasporic position as an important lens for thinking through Black futurity, Black female bodies, and Blackness as global and nuanced in its multiplicities and complexities.

JDHow do composition and materiality operate in your collaged figures to move the conversation beyond an identity politics and offer up multiple ways for understanding the Black body?

TSThe figures I create in my work are all imaginary people in imaginary scenarios, but I draw from lived experiences and memories. Many of my subjects are inspired by people I have encountered or seen in the neighbourhoods I have lived in both Harlem and New Haven.

Pop culture icons and subject matters are also a huge inspiration to me. The content in the work generally relates to the existential concerns of the subjects within the paintings. I articulate the complex interiority of my characters through the multiplicity of materials used to articulate their exterior form.

Various materials such as textiles, paper, felt, fur, and fabric are collected and used alongside what I call studio debris, from previous works and failed projects, to create the appliqué elements. Collaging and assemblage allow me to create new ways for audiences to see and perceive the body.

JDI saw your series 'Bodega Run' at Hammer Projects last year and I was struck by your approach to interiority, both architecturally and in the works, to represent social spaces for communities of colour. How do you represent the body in relation to bodegas?

TSBodegas are neighbourhood convenience stores that are important to and representative of Black metropolitan life, particularly in New York City. These stores are arranged or designed mainly to display as many products as possible, so goods are often stacked quite densely.

The bodega is not designed for a shopping experience, but rather for a very specific utilitarian purpose. That purpose being to supply goods quickly and conveniently. Bodegas serve mostly Black communities, however historically, they have been owned by individuals of Latinx descent.

The bodega is an infinitely interesting locale and institution for the various racial, ethnic, and social dynamics at play within these spaces. The mere existence of these stores is deeply radicalised, given the fact that bodegas occupy neighbourhoods that are generally defined as food deserts.

I am interested in inverting perceptions, forms, and meanings, however I am equally invested in shining a light on little-known facts.

These stores provide much-needed resources for otherwise neglected communities. However, these spaces are not entirely positive, and the architecture of these spaces often reflects the general attitudes towards their patrons. Surveillance and security are huge aspects of the bodega aesthetic. Plexiglass barricades and large mirrors are commonplace amongst with low quality and inexpensive foods.

I am fascinated with the bodega because of its many dualities. The stores, like so many institutions within the Black community, are injurious as they are therapeutic.

JDThen, of course, there's the fact that due to gentrification, the bodegas will begin to disappear as neighbourhoods become more affluent and people are pushed out and displaced. Do you feel that the series is in some way historicising these spaces?

TSYes, for sure. Bodegas have already changed, and I believe they will continue to, for better or for worse.

JDYour solo exhibition at the ICA Boston, titled Out of Body, sought to think about Black bodies beyond identity politics. How did this relate to how American society has both metaphorically and in lived experiences disembowelled the meaning of the Black body?

TSThe idea of the body represents so many things that are outside of and beyond identity and identity politics. As an artist, I am interested in inverting perceptions, forms, and meanings, however I am equally invested in shining a light on little-known facts.

The title of my exhibition at the ICA Boston was a double entendre. I was trying to communicate a desire to escape the conventional conversations around Blackness and womanhood, while simultaneously alluding to the spiritual and metaphysical self.

Again, I hoped to spark a conversation around Black existentialism, which is an oxymoron of sorts, because existentialism should and does exist in my mind outside of an identity politic, given that it is a matter of the soul.

JDI interpreted your audio piece for Cotton Mouth as a score to unify the works, giving them a voice. Do you use sound as another layer to further contextualise your work?

TSWas there a particular part of the Cotton Mouth piece that stood out for you when you listened to it?

JDYes, I was struck by the part where you question the origin of Black America, saying, 'If Black America began with slavery, then all mythologies in regard to this new America . . . in turn would be possessed and exist within pop culture.'

This made me think about the exportation of Black American popular culture globally, as I grew up in Nigeria in the 1990s and there was so much consumption of this culture. In some ways, this projects a particular image of Blackness and it's interesting how this plays out in other geographical contexts, or rather when popular culture becomes a dominant form of global culture, power, and capital.

TSI wanted to introduce a voice into the exhibition, and the audio piece, Cotton Mouth, allowed me to do so. What is amazing about the audio piece, is that my voice and monologue function as a manifesto of sorts, whereas the other voices in the piece bring to life the various figures in the works.

The voices in the audio piece allow viewers to imagine the cadence and tone of my subjects. The audio piece really speaks to my desire and difficulty in articulating the rather abstract idea of Blackness as it is typically discussed. I am solving this dilemma in real-time during my monologue.

I come to several conclusions throughout the course of this rhetorical conversation, the main point being that Black American identity is married to ideas of modernism in the West, and this fact is most clearly articulated through the over-representation of Black Americans in popular culture.

JDWhat are your thoughts on the relationship between nationalism and cultural politics in Black popular culture, and what this could reveal about nationalism, globalisation, and cultural politics more broadly?

TSIt is hard to say, because Black Americans have had the most utterly surreal experience here in America. I do not know if anything from our experience can be compared to other peoples in other nations, because our history has been so thoroughly unique.

I hoped to spark a conversation around Black existentialism, which is an oxymoron of sorts, because existentialism should and does exist in my mind outside of an identity politic, given that it is a matter of the soul.

What I can say is that the Black American history of enslavement and the systematic disenfranchisement that Black Americans have experienced since the end of slavery—segregation, redlining, and mass incarceration—have significantly shaped the community's worldview.

JDHow do you engage with the notion or grammar of futurity and transformation in your work to imagine a different future for Black women or the ways in which Black women's bodies are seen and understood?

TSI love this question because this is something I think about often. Honestly, because so much has been hidden from us, Black people here in the Americas and abroad, I believe we must truly learn the truth about our past to find pathways to excel in our shared future.

We must abandon the lies and mistruths we have been told about ourselves and our ancestors. Through reconnecting with our true culture, I believe we can liberate ourselves in this present moment and fortify ourselves for the future.—[O]