Wong Ping: Hong Kong Fables

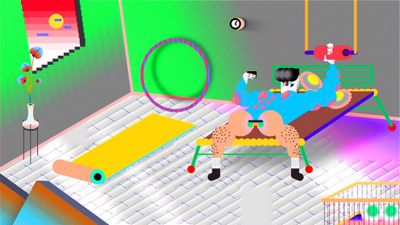

Wong Ping. Courtesy the artist.

Wong Ping. Courtesy the artist.

There is something irrepressibly compelling about the lewd animated videos of Wong Ping. Is it their flat surfaces rendered in popping colours? Or their dark narratives that resonate with the deepest recesses of the human psyche? They have been included in an impressive repertoire of group exhibitions in recent years, including One Hand Clapping at the Guggenheim Museum, New York (4 May–21 October 2018) and the 2018 New Museum Triennial, Songs for Sabotage, also in New York (13 February–27 May 2018). Capping off his remarkable year, the artist opened his first European institutional solo, Golden Shower, a sprawling presentation at Kunsthalle Basel (18 January–5 May 2019) of nearly all of his recent videos, and including several new installations, parts of which will go on to be shown at Camden Arts Centre in London this summer (Heart Digger, 5 July–15 September 2019).

Born in Hong Kong in 1984, Wong Ping did not receive formal training as an artist. In 2005 he graduated with a degree in multimedia design from Curtin University in Perth, then found a job in postproduction at a Hong Kong TV station, followed by a stint at Cartoon Network. Through experiments with software, and drawing on his knack for storytelling and taste for the outlandish, Wong started distilling his day-to-day experiences and perceptions of the world into short animated videos that he uploaded to Vimeo, leading to the foundation of what he called the 'Wong Ping Animation Lab' in 2014.

Moral slippages around lust and desire reveal the perversities of contemporary life—themes that are both universal and relate specifically to the concrete jungle that is Hong Kong, a place 'where you can truly face your lust with no moral laws', the artist has stated in relation to Jungle of Desire (2015), a video portrait of an 'impotent husband, an unsatisfied wife, and a megalomaniac policeman.' The kink in Wong's videos is often enhanced by sculptural elements, all of which can be seen in Golden Shower, where seven films and multiple installations made the artist's work with the image materially palpable.

Wong returned to Basel during the last week of the show's run, surrounded by roughly 4,500 golden sets of wind-up teeth he arranged in a grid in the first room of his exhibition, to discuss his practice with the museum's director, Elena Filipovic. The text below is an edited transcript of the public talk.

EFLet's start by discussing your beginnings, because you came to art in an unusual way.

WPI studied multimedia design in Perth, at Curtin University. I had failed my entrance exams for my final years of high school, so my parents kicked me over to Australia, where they have a friend. During my studies I learned how to use Photoshop. All of that software was still fairly new at the time—I think it was 2001 or 2002. I don't think the professors knew what they were doing, so they just had us experiment with the software. After four years I flew back to Hong Kong, and I found that all the software companies selling the stuff I'd used during my studies had gone bankrupt, so I had no saleable skills in Hong Kong. I couldn't find a job. I didn't know what to do, so I went to the library to look at some new software manuals. I did that for a month and ended up doing some very easy and inexpensive Adobe After Effects work and sent it to one of the broadcast stations in Hong Kong. I guess at the time they needed cheap labour, so I got the job and started working in a TV station doing post-production for drama shows.

The dramas they made were very bad, very cheesy. Some days I would work maybe ten hours just to create gunfire. If the actors or actresses had bad skin, I smoothed it out. One time a famous actor ran into the post-production room and asked me to edit his acne out of the scenes he was in. I had to spend two days smoothing out his skin, which was really frustrating. At that point, I started to wonder what I was doing there. I think I worked there for two or three years. I didn't yet have much interest in art, but while doing the post-production my mind wandered. Often I would go home in the evening and write blog entries. I kept an archive of random stories. That's when I started writing.

EFSo the writing came first for you, before the image?

WPYes. I didn't even know how to draw or do animation at that time. As a young labourer I didn't have a contract, and eventually got fired along with five or six other employees at the TV station. But I guess I did a great job smoothing out skin, as one of the bosses passed me the card of someone at Cartoon Network, and they hired me without an interview even though I knew nothing about cartoons or motion graphics.

EFSo that was your new day job?

WPYes. I would finish work early and have to sit there and pretend I had something to do. One day I opened up Illustrator and taught myself to draw with points and paths—vector drawing. That's how I started my simple drawings, which I posted online.

EFAnd you posted them on YouTube?

WPNo, at that point they were just still images, which I posted on Facebook. At 25, I still didn't know how to make video. But an indie band in Hong Kong saw my work and invited me to do a music video for them. Even though I had never done animation! I took the chance and produced a few more videos with other bands, and that led me to start posting my videos on Vimeo, which is similar to YouTube. But still, my work was mostly online. I hadn't yet shown it in a physical art space.

EFEven until rather recently, most of your work has been known to people via Vimeo or YouTube. It is interesting to me that when you finally started contributing to group shows and exhibitions, you had to start thinking about the difference between people seeing your work in the privacy of their home, on their computer screen, and about how the flat image could take up space and be public at the same time.

WPTwo or three years after I started posting my work online, an artist from Hong Kong, Nadim Abbas, saw it and invited me to participate in his Absolut Art Bar installation at Art Basel Hong Kong in 2014, I created an eight-channel animated video installation that related to the apocalypse. I did that, and then I got a commission from M+ to create The Other Side (2015), a two-channel animation that touched on themes of migration. Those were the first times I jumped out of the virtual world and did something in physical space.

EFThe show at Kunsthalle Basel has been so popular in great part because of its singular combination of simple, colourful, almost childlike graphics, yet very deep, sometimes dark stories that they're telling. Does writing still come first for you, now that you have established a visual language?

When you were here preparing the show, one of the things we talked about was the logo for Wong Ping Animation Lab that appears at the end of each film, which gives the impression that there's an army of assistants working with you. Yet, you write the stories, you draw out all of the animations, you often make the music, and you even do the voice-overs for almost all of them—except for the series, 'Wong Ping's Fables' (2018–ongoing). You are your own one-man animation lab.

WPI created the Animation Lab because I was applying for funding to do one of my pieces, and the Hong Kong government needed me to have a company. I once tried to outsource work to another animator I know, but they were just too good—the work was too smooth and I didn't like it, but I still had to pay them! So I vowed I'd never do that again. Also, during the process of making the work, there's a lot of suffering that I have to go through in order to get better. It's as if I were to walk from Hong Kong to Basel—I would get a lot of experience, have to make a lot of choices, and would get to know myself better, even if practically speaking, the end result was the same as if I flew.

When I write, I don't think about the visuals, and when I do the visuals I don't think about the story. But during the process of animation, I make changes to the story. I also occasionally encounter accidents that sometimes turn out really cool, so I leave them intact. All of this comes from my imagination. I can't get someone else to do it.

EFCertain films, such as the 'Fables', do not include your voice.

WPIt's because the 'Fables' mark a new direction in my work, away from those that relate heavily to myself. I wanted to make something for children, with a story lacking sexual content or violence. I wanted people to feel the dark side of the story without having to see blood or genitals. They're fables, so they use a motherly digital voice. I hope 'Wong Ping's Fables' can one day replace Aesop's Fables in the library.

Before doing 'Wong Ping's Fables', I did a lot of research and read many big-name fairy tales, and I found they weren't really practical for today's society. For instance, I know I have to be good to my parents, but it's hard to do that when I'm away a lot and I can't spend more time with them. I wanted to write something that's very honest, that tells kids that they don't have all the time in the world to be with their parents, friends, or lovers—that's just a fact.

EFYou brought it up already a little bit, but I want to address the elephant in the room: sex. So many of the works preceding 'Wong Ping's Fables' contain explicit sexual content. Of course critics pick up on it and ask you about it again and again, so, sorry to ask one more time! But on one occasion you answered the question by saying that sex is not the subject of your films, it's just the language you use to make them. Why does this content feel relevant and important for you, with this kind of form, at this moment?

WPWhen I first started doing the animations, I didn't expect people to focus so heavily on the sexual aspect. Sex is everywhere, after all. It's just like gangster movies from Hong Kong—one director might only ever produce gangster movies, but no one asks, 'Why always guns? Why always gangsters?' With romance directors, no one asks, 'Why always love? Why always romance?' Sex for me is like the guns in gangster movies—it's just the language of my work. In gangster movies they don't always specifically discuss how the gangster families are made up, but they do still touch on families, business, society, life, loyalty. Wong Kar-wai always talks about love, but underneath he's talking about other things as well, although I haven't seen a lot of his work.

EFOnce you'd set up the show here, you wondered whether people in Basel would understand the work because to you it feels very 'Hong Kong', whereas I don't see the works as very Hong Kong, necessarily—I see them as universal stories about society, humanity, relationships. How much does Hong Kong—its aesthetics, and as a society—impact your thinking and making of the stories?

WPHong Kong is very heavily populated, and a lot of weird stuff happens in the street, thus I find that I end up doing a lot of Instagram stories there. Because I live in Hong Kong, my writing and thoughts come from there. It would be weird if I was constantly referencing Africa or Iceland. Although it's true that nowadays, with the internet, we all share similar views and similar situations.

EFEach of your films starts with a story, and that writing is extremely personal, even if it emerges from something that you see on the street or an article you read in the newspaper. For instance, could you tell us about the starting point for the animation Dear, can I give you a hand? (2018)?

WPOne day I was bicycling in a park in Hong Kong. It was a weekday, so there weren't too many people around. I happened to pass by an old man in a white singlet and black pants—typical Hong Kong fashion—with not much hair, holding a huge bag, which he threw into a trash bin. I saw a lot of flesh colours flash by. I checked the bag, and it turned out to be VHS tapes of Japanese porn. The condition of each one was very good—the booklets in each case looked fresh from the printer—so I guess he must have loved all of them. This was two years ago, a long time after VHS, DVD, and even Blu-ray were in use. Although I suppose I don't know if there is such a thing as Blu-ray porn. I thought about keeping the tapes, but I didn't have the right player, so I just went home and wrote the piece instead.

In looking through all the tapes, I noticed the government advisory to recycle the film tape separately. I considered asking the old man to do it, but in the end I didn't—I mean, he already seemed so sad. Watching his back receding toward the sunset, I understood how he felt. On another occasion, when walking around the city, I came across a stall selling USB sticks with porn on them. I think the target audience was the elderly, which made me wonder how they watch porn today. I mean, if they can go online to watch it, why would they need a USB stick to access it?

My works always reference my diary, where I record hundreds of things I've seen or been through during any particular month. At the time I was making Dear, can I give you a hand?, my grandmother was in a retirement home. The condition of those homes is quite bad in Hong Kong, and whenever I visited her, the room was dark and everyone was sleeping. They would wake up for a meal and then go back to bed—just waiting for the next visit from family. So that's something I want to focus on—the ageing problem between generations.

EFDear, can I give you a hand? is an excellent example for understanding how you construct your stories, because you brought in not only a scene you witnessed in the street, and your own thoughts about what you would have told the old man you encountered, but also your own life experience with your ageing grandmother—all of these things end up becoming the narrative. Jungle of Desire (2015) has a very different starting point.

WPJungle of Desire was part of my first solo show in Hong Kong, at Things That Can Happen, so I was still figuring out what I was doing. Over the years, I had read about policemen taking advantage of sex workers by asking them to provide free services, and arresting them if they didn't. Things That Can Happen was situated in the lowest-income area of Hong Kong, and there is a lot of sex work there, so it felt like the right time and place to write that particular story. The second half of the piece imagines a revenge murder of the cop, so it goes a little off topic. I put all these lucky cats in the space, but I replaced the arms with penises. At the end of the show I donated about half of those cats to an organisation that supports sex workers.

EFThis is the perfect moment to speak about the difference between the way you think about making a film, and how it becomes an installation. One of the rooms at Kunsthalle Basel is surrounded by The Ha Ha Ha Online Cemetery Limited (2019), a vast number of wind-up toys that reference Dear, can I give you a hand?, the film being shown in the same space. The third room of the exhibition contains about 100 of the lucky cats you mentioned, as part of the presentation of Jungle of Desire, and in the last room are two monumental inflatable objects, so each room has a sculptural dimension.

We could even talk about the fourth room, which contains the work you call BONER (2019), a giant phallic totem that showcases three different films and has a rotating head shaped like a heart. So it is clear that you're not just making two-dimensional images, but someone thinking in the form of installations and sculptures.

WPIt's not easy for me to make objects, but I always want to make them because I get sick of looking at the computer monitor and want to see something physical. If one day there was no more power or electricity, and you and I were alone on an island, I wouldn't be able to convey my visual work to you because it's all on computers and requires power to be seen. When I think about that, I feel really pathetic. Making objects is always an interesting expansion from my work, like the gold teeth. My grandma used to have a full mouth of gold teeth. Nowadays they use ceramic or porcelain instead of gold. Hip-hop singers and rappers have gold teeth, but I found out that some of them use fake gold, so I guess my grandma is cooler than them. Maybe my grandma was a rapper.

These works are expansions of my videos—they contain elements that don't fit or that I don't think are suitable for the films. I still have some difficulty thinking about how to present or use space. The use of space is a new consideration for me. People in the art scene talk about it very easily, but I feel I am still figuring it out.

EFI think you're doing pretty well.

WPIt's more that I feel unstable, because I have no idea what I'm doing. It's quite dangerous and frightening. I remember when I did that first commission for M+. I wanted to include a TV, and the curator asked me what I wanted to put it on. I suggested a table with four little black legs, and when he asked me why, I said I just thought it would look good. Until I came up with a reason why, he said, he wouldn't let me do it, and if I didn't come up with anything, we'd put it on a white plinth. I said white is boring; he said no, in the art field it's neutral and invisible. I replied: 'It's not invisible! It's white and sticks out from the floor!' These kinds of conversations push me to learn, but at the same time question more. That curator and I are still very good friends.

EFWell that's good! I think the fact that you see things that people who are long programmed by the art world don't or can't see anymore, is probably what gives your work such force. You don't just assume that a white pedestal is the obvious way that something should be presented. I remember the first time we brought you in for a site visit, and you walked into the first room and you were just amazed, staring at the ceiling; no matter what, we couldn't make this a black box—meaning, turn out the lights and make the architecture disappear. You wanted everyone to be able to see the space while they were viewing your animations and installations, so that they would experience the same feeling of marvel.

My point is that if you hadn't come to see the place, if we had just emailed floor plans back and forth, we might easily have turned this into a projection room. But you wanted the room brightly illuminated, which meant we got LED screens instead. It also meant that you could think about the long walk required to get to the film, and the space around it. The gold teeth on the walls are almost like pixels—like a digital overload.

WPThe first time I showed Dear, can I give you a hand? at the Guggenheim, the teeth were placed on the ground behind the LED screen. It was a whole floor of them, but with smaller versions of the teeth, and they all got stolen—in about a week they were gone. That show was last year, and last month a guy on Instagram tagged me in a picture of him holding up two sets of teeth, saying that he stole them. I forwarded it to the curator, Xiaoyu Weng, and she left a comment telling him to give them back, and then he followed her and liked her posts. It was funny.

On another occasion, for my 2017 solo show Who's the Daddy at Edouard Malingue Gallery, I put 15 crawling baby toys with VR goggles in the space. They were crawling all over the space, and at the opening, a collector asked me if he could have one. I said he'd have to talk to the gallery; I couldn't make the call. The day after the opening, I realised one of the babies was missing. I made a post on Instagram calling out whoever had taken it, not knowing who this might be. The collector then messaged me saying it wasn't him.

EFWell, we're pleased that we didn't lose any teeth! I want to ask you one thing I've always wondered: have your parents seen your films? And if yes, what do they think?

WPThey don't get the humour. They don't understand what I'm doing or how I could possibly make a living from it. I told them I don't either, but as long as I have a room to live in and money to eat, they're happy. Whenever I finish my works I show them to my parents and my brother, but I don't know if he likes them, because he's Christian.

EFWhen you were first making your films at home and uploading them to the internet, they were meant, in a way, to be watched by people in the privacy of their own homes. In the exhibition context, people are not only watching the films, but other people are watching them watching. I wonder about privacy versus public-ness in your work.

WPI've always uploaded my work online. Even some of the latest work can be seen privately. In an art space, I'd rather do it another way. It's up to the visitors whether to feel shy or embarrassed—that's their problem. But I especially like to see how children respond to my work. They laugh at different parts of it than the adults do. I always think it's fine and safe to let children watch some of the outrageous content because I don't think they necessarily understand what's happening. They just find the motion funny.

EFCould you ever have done a show like this one in China?

WPI guess not. I tried so many times to upload my stuff to Chinese websites at the beginning, six or seven years ago, and always failed. I would try to change the title to something healthy, like 'Eat More Vegetables' or 'Do More Exercise' and it still got blocked. At that point it didn't matter whether I could upload it or not—I just wanted to test the firewall. I realised that they must be checking it manually, which is crazy. To make a show in China you have to go through all the censorship departments, and I'm not interested in that.—[O]