Bruce Nauman: Beyond the Comfort Zone

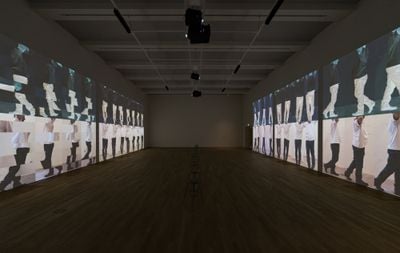

Bruce Nauman, Contrapposto Studies, I through VII (2015/2016). Seven-channel video (colour, sound, continuous duration). © 2024 Bruce Nauman / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Jointly owned by Pinault Collection and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Photo: Jimmy Ho.

You don't have to like Bruce Nauman's work. In fact, many don't. The Indiana-born, New Mexico-based artist's exhibitions have confounded the wider public and critics alike.

In a frequently cited quote from a 1987 interview with critic Joan Simon, the artist himself has described the impact of his work as being 'like getting hit in the face with a baseball bat. Or better, like getting hit in the back of the head. You never see it coming; it just knocks you down.'

A major institutional survey at Hong Kong's Tai Kwun Contemporary, Bruce Nauman (15 May–18 August 2024), spans six decades of the conceptual artist's experimental career, from the 1960s until today. Co-curated by Carlos Basualdo of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Caroline Bourgeois of the Pinault Collection, and Tai Kwun's Pi Li, the exhibition presents 35 works, from early neons to the recent 'Contrapposto Studies' series (2015–2019), alongside drawings and large-scale sculptural and sound installations. While the works may seem disparate, there are ideas Nauman circles back to limits, time, and control. What can art be? What are the boundaries of space and of language? How much can the body endure? How much can the audience endure?

I dreaded seeing another Nauman show and confronting the unease that underscores his work. His videos are characterised by repetitiveness and banality. Some can feel downright hostile—they swallow up your time and patience, akin to a psychological assault. Discomfort and boredom are feelings we try to avoid. We live in a culture that caters to our desire for convenience and ease. With Nauman's work, we are encouraged to confront and sit with that discomfort.

The conceptual starting point to the exhibition, installed in Tai Kwun's entrance window like a glowing advertising sign, is The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths (Window or Wall Sign) (1967). One of Nauman's first neon signs, the work was inspired by a commercial beer sign and fuses the mass culture of signage and advertising with the 'high' culture of art. The cursive titular message spirals from the inside out, a cliched statement that is both facetious and serious, prompting viewers to reflect on the role of art and the artist.

From within the museum emanates a cacophony of voices from the 21-channel audio stream of Raw Materials (2004), which marches visitors into the building and up the spiralling staircase like an anxiety-inducing drumbeat. Words and phrases are endlessly repeated— 'thank you, thank you'; 'No, no, no, no.'—as is a never-ending joke: 'Pete and Repeat are sitting on a fence. Pete falls off. Who's left?' Repeat. Over and over.

Entering the first gallery space is disorientating. We are hit with a further wall of dissonant sound, the blue glow of flickering television screens, the buzz and flashing of neon, and an overload of information, visual and sonic. Nauman's exhibitions often come with a dose of anxiety. Punctuating the austere space is a scattering of nine televisions on plinths, presenting Nauman's video performance pieces—the products of solitary activity in which we see him undertaking repetitive actions, often violent, no doubt often painful. Featured in a close-up, he repeatedly and aggressively yells, 'Thank you!' (Thank You, 1992), parades back and forth in a narrow corridor, exaggeratedly swinging his hips from side to side (Walk with Contrapposto (1968)), bounces in and out of frame, yelling 'think' (Think (1993)), and continuously crashes his body against a wall (In Bouncing in the Corner, No.1 (1968).

A medium of mass culture, the neon works buzz with glowing words. Citing the writings of philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein and his sprachspiele (language games) as an influence, Nauman's work playfully subverts linguistic expectations. Using palindromes, anagrams, and absurdist commands and statements, Nauman's videos, neons, and works on paper emanate unease. One bright-red neon alternately flashes the word 'WAR', like a warning, with its inverse 'RAW' (Raw War, 1970-1972). A 1968 drawing Nauman made for the neon (not shown) instructs: 'Sign to hang when there is a war on.' It may as well be on permanent display.

Another neon hanging nearby reads Eat Death (1972), with the word 'Eat' superimposed over the word 'Death'. Nauman expands on this idea of violence and consumption with Animal Pyramid (1989), a macabre-yet-carnivalesque spectacle in which 17 life-sized, ready-made taxidermy moulds of deer, caribou and foxes are stacked almost four metres high. Displayed in a separate exhibition room, Animal Pyramid resembles a pile of hunting trophies, alluding to humanity's appetite for violence.

In his 1987 interview with Simon, the artist also stated, 'My work comes out of being frustrated about the human condition. And about how people refuse to understand each other. And about how people can be cruel to each other.' To that, we may add other species, too. But, while Nauman critiques our culture of insatiable consumption, his works have themselves become commodifiable spectacles. I watch a smiling, designer-clad, Birkin-toting influencer pose in front of the installation before another soon takes their place. Repeat, one after another. Today, much of Nauman's work's abrasive discomfort and alienation can easily be shrugged off or ignored. There is a tension, and a gulf, between his emphasis on the human condition and the slick aesthetics prioritised by our digitally saturated, commodity-obsessed culture.

The most disquieting of the video works—especially if you're not a fan of clowns—is from the artist's iconic 'Clown Torture' series. Clown Torture (I'm Sorry and No, No, No) (1987) is a two-channel video installation in which the visitor stands between two television screens showing footage of clowns. On one, a 17th century Pierrot stamps his feet and shouts, 'No, No, No' in every emotional intonation. On the other is a red and green Jester's face, with exaggerated and sinister expressions, manically repeating, 'I'm sorry for what I did. I don't know why I did it.' The viewer is caught in a volley between comic despair and terror on one side and diabolical mania on the other. The overall effect is a sense of horror and comedy. Humour and distress are inextricably linked. We laugh the pain away while being dragged by an uncomfortable undercurrent.

Nauman's work is not so much about the sublime as it is about the mundane. Everyday life—a situation, a process—can be art; the body and the studio space can be sites of creative production. He shows that anything—even repeatedly walking down a corridor, as he does in 'Contrapposto Studies: I through VII' (2015–16)—can be art. Setting a Good Corner (Allegory and Metaphor) (1999) is filmed outdoors, on the ranch in New Mexico where the artist has been living since 1979. Filmed in one shot that runs for almost an hour—the total length of the video cassette—the footage shows the artist, dressed in a cowboy hat, shirt, and jeans, carefully and purposefully building a fence on his ranch. Unlike the corner he backed himself into in Bouncing in the Corner, this work is almost peaceful and meditative.

Perhaps it is the artist's older age or being outdoors, but Setting a Good Corner feels liberated from the hemmed-in anxiety of his earlier works. Seated on a bench as we watch the video, we eventually submit to the artist's repetitious, quiet, and deliberate movements as he goes about his task until completion. It recalls a quote by the composer John Cage, whose work the artist references in a later video (Mapping the Studio I (Fat Chance John Cage), 2001),'In Zen, they say: If something is boring after two minutes, try it for four. If still boring, then eight. Then sixteen. Then thirty-two. Eventually, one discovers that it is not boring at all but interesting.'1 On a continuous loop, the video seems an apt allegory for the daily grind, the rhythm, and repetition that makes up our lives, the passage of time.

We look for spectacle and distraction, but Nauman shows that tedium and procrastination can be acts of creativity. Perhaps we must resist that compulsion to move on, flit from screen to screen, and sit instead for a while with our own discomfort and boredom. —[O]