Japan Focus: Three Tokyo Exhibitions

I walk along Tokyo’s Ginza shopping street towards the basement art gallery of Shiseido’s store, where three series of recent works by renowned Japanese photographer Nobuyoshi Araki are on display in Nobuyoshi Araki Ōjō Shashū: Photography for the Afterlife — EasternSky. It’s one of those autumn days when the clouds feel very high in the sky.

Children dressed as pumpkins and witches rattle past me like wind-up toys. I feel like I’m in Ginza (2014), Araki’s monochrome series of street photographs that greets visitors as they enter the gallery. Araki worked in an advertising agency on the Ginza in his youth, spending his lunch hours photographing the street, and the images on show today retrace his footsteps.

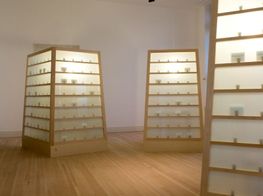

Nobuyoshi Araki Ōjō Shashū: Photography for the Afterlife - Easternsky. Exhibition view, Shiseido Gallery, 2014. Credit: Ken Kato

The second series, Eastern Sky (2014), is similarly monochromatic, but moodier—and this time Araki points his camera upwards. Since the Great Eastern Earthquake of 2011, Araki has taken a photograph from his rooftop each morning, and thirteen of these are included in the exhibition. Looking east towards the origins of the disaster, Araki captures diverse cloud forms and the luminescence of the rising sun. The act simulates both that of looking to the heavens at times of crisis, and a searching—namely, for the invisible rays of nuclear radiation left in the wake of the Fukushima disaster, caused by the tsunami and earthquake. Hung in window alcoves about a metre above the Ginza works, Eastern Sky invites us to look beyond our immediate surroundings, at what is at stake politically and emotionally in Japan today.

Nobuyoshi Araki Ōjō Shashū: Photography for the Afterlife — EasternSky, Exhibition view, Shiseido Gallery, 2014. Credit: Ken Kato

In contrast, the third series’ boldness and colour take us from the street and sky, into the studio. Paradise (2014) comprises 55 photographs of flowers and children’s toys isolated against black backgrounds. On closer inspection, dismembered plastic dolls and phallic stamens introduce a darker twist characteristic of Araki. The flowers are wilting, which creates a historical link to the vanitas genre, and signals Araki’s current thinking. Having lost his wife, survived cancer, and mourned the death of his cat Chiro, the images are memento mori for Araki’s personal losses—as well, perhaps, as those of his country. As I rejoin the street and its Halloween-clad children, I’m reminded of the memorial origins of All Hallows, a context in which Araki’s photographs feel particularly poignant.

Mori Art Museum

Lee Mingwei and His Relations: The Art of Participation - Seeing, Conversing, Gift-Giving, Writing, Dining and Getting Connected to the World

Until 4 Jan 2015

Memorial flowers also feature in Taiwanese artist Lee Mingwei’s first retrospective, currently at the Mori Art Museum in Roppongi. Broadly fitting into the school of relational aesthetics, Mingwei employs everything from flowers and food to large-scale sewing projects in his efforts to engage with audiences and create unusual experiences. In a slightly more personal work, 100 Days with Lily (1995), five large photographic close-ups of Mingwei going about everyday life are overlaid with text. In each photograph, a potted lily in bud, bloom or decay is visible next to Mingwei. The text lists Mingwei’s activities for 100 days, for example, ‘Day 18. 22:13. Reading with Lily.’ On day 88, the lily dies, but Mingwei continues to live with it. Made in the period following the death of Mingwei’s beloved grandmother, the work is both an insight into Mingwei’s tender and precise practice, and a suggestion of how mourning might be woven productively into our lives. In this, an act personal to Mingwei becomes a mourning and thanksgiving method we could adopt too—as with Araki’s daily photographic ‘prayers’ for Fukushima, in Eastern Sky.

Lee Mingwei, The moving Garden., 2009/2014. Exhibition view, Lee Mingwei and His Relations: The Art of Participation - Seeing, Conserving, Gift-Giving, Writing, Dining and Getting Connected to the World, Mori Art Museum, Tokyo. Photo: Yoshitsugu Fuminari. Photo courtesy Mori Art Museum, Tokyo Mingwei studied weaving at California College of the Arts, and he likens relational aesthetics to weaving, in its combinations of collective effort and disciplines. Participatory works such as The Mending Project (2009) are central to Mori’s retrospective. Monitors placed around the gallery broadcast Mingwei explaining each project and its motivations. On the 11th September 2001, Mingwei was living in New York. In the hours following the attacks on the world trade centre, he opened his house and provided food and shelter for those unable to go home. As he sat talking with his visitors, Mingwei mended garments. He patched his trousers, darned his socks, and planted a seed in his mind that would eventually become The Mending Project. Each time the project is installed, Mingwei or a helper sits in the gallery and mends items of clothing brought in by the public. Items remain attached to the spools of thread with which they were mended, and the spools are attached to the gallery wall. For the duration of the exhibition, the items accumulate as evidence of a collective effort to repair and make good.

Lee Mingwei, The Mending Project, 2009/2014. Exhibition view, Lee Mingwei and His Relations: The Art of Participation - Seeing, Conserving, Gift-Giving, Writing, Dining and Getting Connected to the World, Mori Art Museum, Tokyo. Photo: Yoshitsugu Fuminari. Photo courtesy Mori Art Museum, Tokyo.

The exhibition also includes a section displaying works selected by Mori’s curator, Mami Kataoka, including Rikrit Tiravanija, John Cage, and Allan Kaprow. In its exploration of the etiquette and gestures of giving and receiving, Kaprow’s film and photographic series Comfort Zones (1975) relates to Mingwei’s The Moving Garden (2009), a piece instructing visitors to give strangers a flower en route home.

Guernica in Sand (2007) is perhaps the most interesting work in the exhibition given its delicate intricacy, and development over the duration of the show. Picasso’s iconic anti-war painting is recreated on the floor using coloured sand. Exploring forces of destruction and creation, Mingwei invites participants to walk barefoot on the sand, one at a time, from sunrise to sunset on one day. As people walk over Guernica, destroying its form, Mingwei will try to reconstruct it. And at the end of the day, the sand will be swept into a pile, and remain in this deconstructed state until the end of the exhibition.

Lee Mingwei, Guernica in Sand, 2006. Performance view: Chicago Cultural Center, 2007. Photo: Anita Kan

MAM Project Space, Mori Art Museum

MAM Project 022: Jacob Kirkegaard

Until 4 Jan 2015

Mori’s ‘MAM’ project space for emerging talent features work by Danish artist Jacob Kirkegaard, who explores the impact of Fukushima’s radiation. Stigma (2014) is a vertical format fixed-shot film of four natural landscapes in Fukushima. Sonic field-recordings are layered in resonant drones over shots of mountains and forests, appearing beautiful and ominous at once. Viewers sit on floor cushions looking up at the huge projection as if through a window and, placed at the end of Mingwei’s exhibition, Kirkegaard’s installation offers a space for more solitary contemplation. Sun gradually pours into a shot of rustling woods, and I’m reminded of the view of treetops from Mori’s windows, of the sun and the clouds from Araki’s rooftop, and of Ginza’s golden light this morning. Meditations on Fukushima and deconstruction (natural and manmade) feature in all three exhibitions. But through the artists’ emphasis on collective effort, and their acute sensitivity to the sights and sounds of particular places, the power of resilience also shines through.—[O]