TarraWarra Biennial: Thoughts on Time and Space

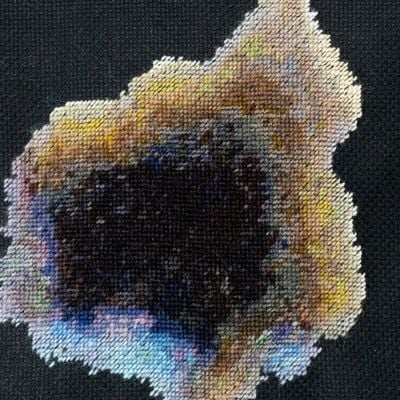

Megan Cope, Currents II (2018) (detail). Exhibition view: Slow Moving Waters, TarraWarra Biennial 2021, TarraWarra Museum of Art (27 March–11 July 2021). Courtesy the artist and Milani Gallery, Brisbane. Photo: Andrew Curtis.

The 7th TarraWarra Biennial (27 March–11 July 2021), organised by the TarraWarra Museum of Art and curated by Nina Miall, contemplates the politics of time by way of the multiple histories of the Birrarung, otherwise known as the Yarra River.

With 49 works presented in all four galleries of the museum by 25 artists all based within so-called 'Australia', the core theme of this year's Biennial is slowness.

The exhibition's title, Slow Moving Waters, comes from the approximate translation of the museum's namesake, the local Wurundjeri Woiwurrung word, 'Tarrawarra'—a theme echoed in Making the Birrarung (2021), a collaboration between Wurundjeri Elder Aunty Joy Murphy Wandin and Wiradjuri and Kamilaroi artist Jonathan Jones.

Engaging with temporality as a present and intrinsic property of its composition, the serpentine arrangement of hundreds of cast-bronze mussels considers two different stories of how the Birrarung river came to be.

Billi-Billeri's account describes Woiwurrung headmen Bar-wool and Yan-yan forming the river by cutting a series of channels with stone axes, while the account of William Barak—the last traditional Ngurungaeta of the Wurundjeri-wilam clan, to whom Aunty Joy is a great-great niece—depicts the river emerging from a stream of a young boy's tears.

The tale is captured in a sound recording, in a dialogue between Aunty Joy and her grandson. Much of the narration is intentionally indiscernible, which is a provocation to attend with more care to the transmission of stories by community Elders.

By condensing narratives of the Birrarung, Making the Birrarung repositions and suspends the water's history into a contemporary arrangement. The gesture is perhaps one of the exhibition's most successful exercises in storytelling, wherein the two artists offer a material reimagining of the river's birth.

Other works on view conceptualise measured time as a means of governance, positing deceleration as a form of institutional disturbance. Palawa, Tasmanian Aboriginal artist Mandy Quadrio's Whose time are we on? (2021) consists of large, overhead drapings made of steel wool that cast shadows in one corner of the museum's first room, emulating a metres-tall tree trunk and pendulum.

The installation's form creates a kind of momentary dwelling, while the abrasive wool represents the ongoing crisis event of colonialism and the continued erasure of Aboriginal peoples.

As Jan Oliver observes in the catalogue for Quadrio's 2018 exhibition Speaking Beyond the Vitrine at Metro Arts in Brisbane, Quadrio uses this 'harsh material to speak to the intentional and legally sanctioned attempts to "scrub out", to annihilate and to commit genocide on her palawa (Tasmanian) people.'

Sharing a wall in the next room are Bangal (2018–2019) and Wunan (2019) by Wiradjuri artist Nicole Foreshew, and Gemerre (2008) by late senior Gija artist P. Thomas Boorljoonngali.

Bangal consists of five wooden sticks roughly painted with ochre, Wunan is a crumpled sheet of found oxidised iron simulating a patch of cracked earth, and Gemerre depicts a series of concentric white ochre lines painted on three black boards and one deep rust red.

This gathering can be viewed as an intergenerational exchange. Bridging generations, Boorljoonngali and Foreshew have been in dialogue for many years, and both artists display a practice in deep listening. Early on, they would share stories with each other—of earth and song, about body and skin—and exchange material objects from Country, around a framework based on Wiradjuri and Gija narratives.

With 49 works presented in all four galleries of the museum by 25 artists all based within so-called 'Australia', the core theme of this year's Biennial is slowness

Grant Stevens' durational moving image work in the same room, titled Below the mountains and beyond the desert, a river runs through a valley of forests and grasslands, towards an ocean (2020), presents a different example of a re-scaling of time.

Displayed across two screens is an imaginary environment, procedurally generated by computer graphics using a method where algorithmically created data embeds randomness within the (eco)system.

As the video moves through different landscapes of mountains and forests and oceans, we witness the cyclical rhythms of nature through the changing of seasons and the evolution of an interdependent, artificially intelligent real-time system. The work's rendering is simple, but its proposition of reproducing time is arresting nonetheless.

Suspended before a floor-to-ceiling window in the next gallery is a trio of ice sculptures of various shapes and sizes, for which Quandamooka artist Megan Cope collaborated with marine biologists.

A work in progress, with the blocks of ice re-installed every Friday, Cope tells me that Currents III (freshwater studies) (2021) reflects the value she has found in the convergence of Western science and Aboriginal systems of knowledge.

Described as a 'live painting', the ice cores, imbued with plant extracts that act as natural pH indicators, quietly melt and stain three large paper discs made from algal blooms that sit in large black concrete bowls. The kinetics of this work is subtle, yet unambiguous in its gesturing (or staining) toward environmental crisis.

Sharing space with Cope is Louisa Bufardeci's eight needlepoint works Looking into the land attached 1-8 (2020), presented on a single wall. Each needlepoint is a transcription of the silt on the artist's feet following a swim in the Birrarung, as viewed under a high-powered microscope.

Despite being the only two works in the smallest of the four main spaces, Bufardeci's needlepoints are overshadowed by the scale of Cope's installation, which points to an issue of spacing.

At times, the exhibition can feel crowded, with works that feel too large for the rooms they are placed in. In a museum with limited space, even the inclusion of 25 artists—a relatively modest number for a biennial exhibition—can detract from the show's ethos.

This is not to posit abundance as antithetical to slowness, but in some cases the lack of physical room threatens to weaken the curatorial argument for deceleration and an audience's experience of it.

For example, the museum hallway, which accounts for one of the show's four galleries, houses five works by five artists, including three small embroidered works by Raquel Ormella depicting phrases such as 'As I wake' and 'Day in, day out', each accompanied by a screen showing an animated video of the work's process.

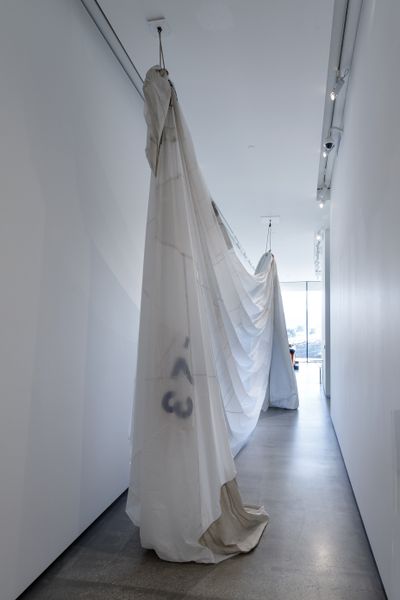

A series of installations includes Freak Out, Far Out, In Out (2021) by Lauren Brincat, a cascading sailcloth held up by church bell ropes that draws a parallel with the winding Birrarung, and Michaela Gleave's The World Arrives at Night (Star Printer) (2014), a dot matrix printer with paper capturing information related to stars that lie above the Tarrawarra spilling out of it.

Lucy Bleach's sizeable installation, attenuated ground (the slow seismogenic zone) (2021), located at the end of the hallway, comprises a toffee-soaked double bass lying upon a plaster plinth, emitting sounds from exposed strings that are activated by tactile transducers, picking up the infrasonic pulse of earthquake events in the Japan Trench.

To dedicate a fairly narrow area to five works makes them feel unresolved, and does a disservice to the show's 'slow and steady' self-characterisation—particularly because the exhibition guides us to this hallway as its last port of call.

In contrast, the ample space housing Stevens' simulation and Foreshew and Boorljoonngali's dialogue, presented among other works including Yasmin Smith's gnarled forms of ceramic grapevines titled Terroir (2020), induces a slower pace for the viewer to wander, sit with, and absorb the constellations on view.

In the exhibition catalogue, Miall describes the drift of Tarrawarra's 'slow moving waters' as the departure point for the Biennial, which 'reflexively explores ideas of deceleration, delay, and the decompression of time' in order to harness 'the potential of slowness as both a passive and an active means for claiming different forms of agency'.

At times, the spacing and zoning of works does not provide the experiential slowness it hopes to, leaving some artworks, especially in the hallway, feeling inconsequential. However, with thanks to many of its artists, Slow Moving Waters is still a mostly successful expression of this statement. —[O]