Chen Ting-Shih’s Quiet Dissent

SPONSORED | Each Modern

Chen Ting-Shih first came across Picasso's found object sculpture Bull's Head (1942) in the late 1960s. By then, he was already an established Chinese ink painter and printmaker who had been invited to exhibit at the São Paulo Art Biennial for four consecutive editions.

Chen Ting-Shih, Quartet (1995). Iron, 58.2 x 39.5 x 23.6 cm. Courtesy Each Modern.

One of the first Chinese artists to work with the readymade, Chen welded iron sculptures from industrial, agricultural, and everyday objects, including the two rusted metal components comprising Royal Progress (1975) that were salvaged from a shipbreaking yard in Kaohsiung.

Held together by a thin chain, the structures weigh down on their pedestal like the anchor of traditional values in the modern age. The work resonates with an enduring concern of the artist, who experimented with ways of integrating both new mediums and Chinese artistic traditions into his practice.

Royal Progress will appear in Each Modern's solo booth at Art Basel Hong Kong (28–30 April 2024), which will present 41 of Chen's sculptures, paintings, and prints from the 1960s to 1990s. Central to the exhibition will be his iron sculptures, assembled from readymades and found metal parts, that have yet to find the same audience as his prints.

Chen was born in 1913 in the coastal city of Fuzhou, China, where poetry abounds and natural sights intercept the Min River. The great-grandson of a Qin Dynasty governor, he was trained in Chinese classics, calligraphy, and painting from an early age.

When printmaking entered China in the 1930s, Chen embraced the medium as an innovative alternative to traditional Chinese painting and Western oil painting. During the Sino-Japanese War, he contributed political comics to journals under the pseudonym 'Ears'.

Chen moved to Taiwan after the war, where he worked for Peace Daily in Taichung and the Provincial Taipei Library. In 1958, having left his job to focus on artmaking, Chen co-founded the Modern Print Association with fellow artists Lee Shi-chi, Yuyu Yang, and Chiang Han-tong.

By the time Chen participated in the 11th São Paulo Biennial in 1958, he had moved away from realistic wood prints of his earlier practice to delve into the possibilities of art beyond representation. Nature, spirituality, and his training in traditional Chinese art informed his experimentation with shape and form.

'When I started to paint abstracts, Western painting gave me a hint,' Chen once wrote. 'But I should confess I received a much stronger influence from the Chinese arts of stone carving and calligraphy.'

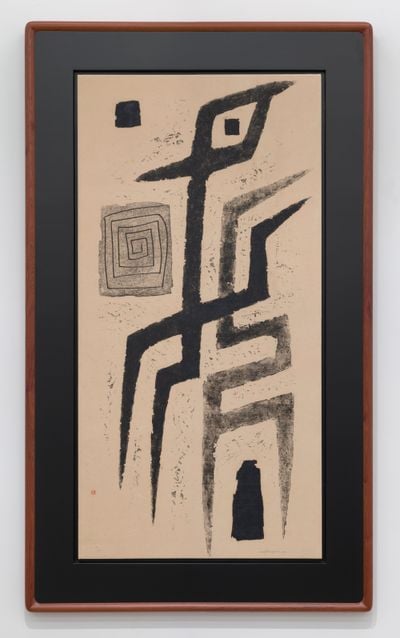

Sugarcane board prints titled TOTEM (1964), for instance, deconstruct calligraphic symbols into totemic structures that are stacked like mountains, bringing a contemporary perspective to seal scripts. Round, angular, or irregular shapes coexist on a single piece of paper in The Beginning of Zen (1965) and The Mystery of Creation 4 (1966), whose titles echo an interest in transcendence and the cosmos.

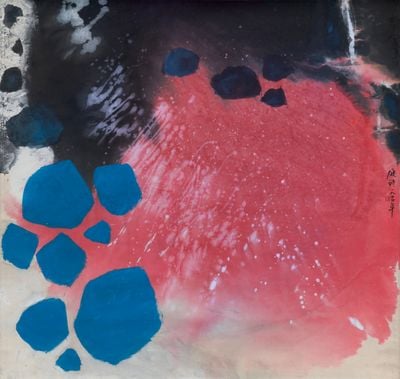

In the colour print Day and Night 70 (1981), abstracted mountains frame a partial sun and moon. Black, red, and yellow denote directions in traditional Chinese painting, and presented horizontally across four sugarcane boards, the landscape introduces a cosmic perspective that hints at a merging of temporal realms, and of old and new.

Chen's sculptural work can be read as an extension of this spiritual inquiry. Harp (1980–1990) shows the titular instrument, made by welding iron, resting at an angle. The repetition of circular motifs, provided by the heavy semi-circle cradling the harp and the small ring at the bottom, evoke celestial bodies while softening the hardness of iron. Taken together, the orientation of the harp draws an invisible diagonal line that sprouts from the earth and reaches for the heavens.

Common objects transform into careful studies of form, weight, and material in Chen's sculptures. Scissors (1970–1980) gathers worker's sickle, scissors, cutting board, and iron components to create a Peking opera mask—a symbol of emotional catharsis and cultural progress in China—with a frowning face. In the elegant Shine (1998), a pair of extremely thin pliers seemingly defies gravity, holding up a metal cog like a trophy.

Presented alongside his prints and sculptures, Chen's paintings in the Each Modern booth appear more fluid. Pigments and traditional Chinese ink mix freely, giving way to large areas of dark and colourful washes, and geometric shapes in The Beach Blossom Spring (1970). The synthesis mirrors Chen's diligent inquiry into the new mediums of his time, in which tradition does not cede way to the contemporary but enters into an ever-evolving coexistence. —[O]