Etan Pavavalung: Poetry for Troubled Times

Etan Pavavalung's paintings draw from woodblock engraving techniques and craft traditions he grew up with as a member of the Davalan tribe, a subpopulation of the Paiwan ethnic group, in Pingtung County, Taiwan.

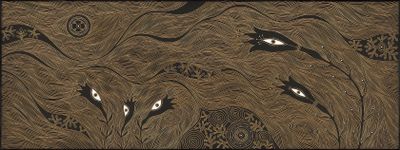

Etan Pavavalung, It is my sacred mountain (I) (2021) (detail). Acrylic and print pigment on board. 90 x 240 x 5 cm each. Courtesy Asia Art Center.

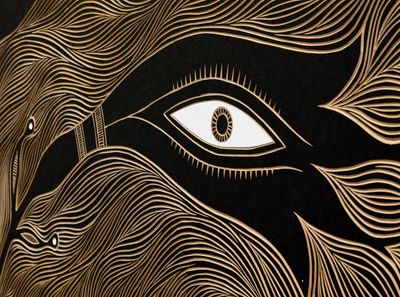

Etan's visual vocabulary draws from 'vecik'—a Paiwan word for images, patterns, or writing that describe natural phenomena, whether forests, mountains, rocks, and streams or wind and rain.

Combining linear geometric patterns and stylised human and vegetal figures, these marks are often incised on wood and stone by men, whereas women would tattoo them on their hands, and weave them into textiles and headdresses.

Etan grew up in a family of pulima, or craftsmen, surrounded by traditional Paiwan artistry and symbols, such as the sun and the lily. His father Pairang Pavavalung is a renowned nose flute maker and graduate of the the Ministry of Culture's Bureau of Cultural Heritage programme.

Born in 1963, he came of age in the 1980s during the KMT Martial Law period and Chinese Culture Renaissance movement. In the 1990s, when awareness of Indigenous rights became more pronounced, Etan officially changed his Han Chinese name back to his Paiwanese name.

For Etan, a tireless advocate and educator of Paiwan heritage, art-making can generate Indigenous community bonding while bridging traditions of spirituality and animism with modernity.

...the transmission of aesthetics, history, and culture in vecik painting draws connections with Aboriginal techniques of expression across the Pacific region...

In 2017, for instance, he created the floor design on which Indigenous singers performed at the opening ceremony of the Taipei Summer Universiade, turning a painted woodcarving of circular patterns into a projection that appeared on 1,200 square metres of LED panels.

The public event seemed to reflect changing perspectives as Taiwan grapples with the struggles and rights of the territory's Indigenous peoples, and Tsai Administration's New Southbound Policy, steering awayfrom a Chinese cultural identity to embrace a transcultural Austronesian heritage shared with countries in Southeast Asia, South Asia, and Australasia.

The transmission of aesthetics, history, and culture in vecik painting draws connections with Aboriginal techniques of expression across the Pacific region, and Etan Pavavalung's sits within this tapestry, as evidenced in the artist's latest exhibition in Taipei.

My Sacred Mountain, Etan's first exhibition at Asia Art Center in Taipei (11 December 2021–27 January 2022), showcases 17 new paintings on fibreboard supports.

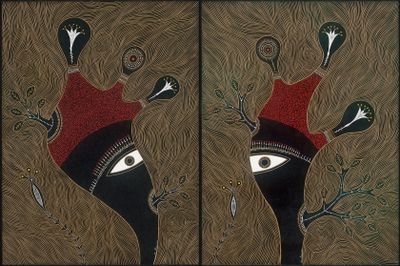

To make each work, the artist chisels figures and patterns into each surface before rolling paint over them, with the sandy-coloured wood grain remaining visible in the grooves. He then meticulously engraves and paints details in.

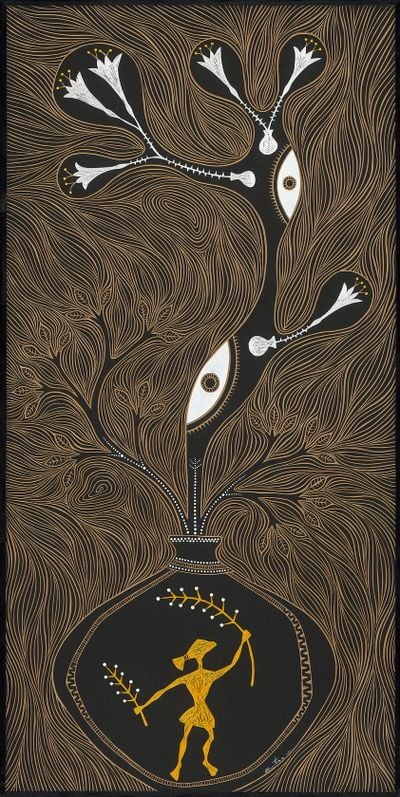

The lily—an important symbol in Paiwan culture—appears throughout Etan's paintings. 'My grandmother used to say that the lilies on the mountain where we lived were there to keep people company,' Etan has said. When they die, she told him, they become stars to guide them from above. The flower was also an icon of the so-called Wild Lily pro-democracy student movement in the 1990s.

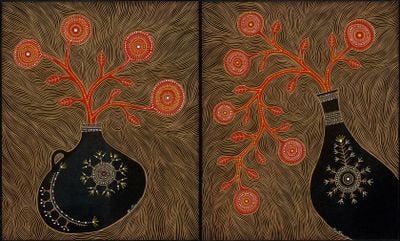

In It is my sacred sacred mountain (I) and (II) (both 2021), two large horizontal paintings depict wavering fields of lilies dotted with eyes, while in I read, discourse in the scape (I), (II), and (III) (all 2021), lilies decorate introspective eyes sprouting from clay pots featuring harvesting farmers and a butterfly native to the mountains of the Paiwan, as flowing lines suggest the presence of wind in the background.

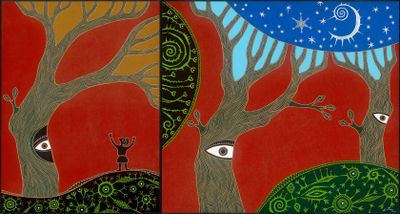

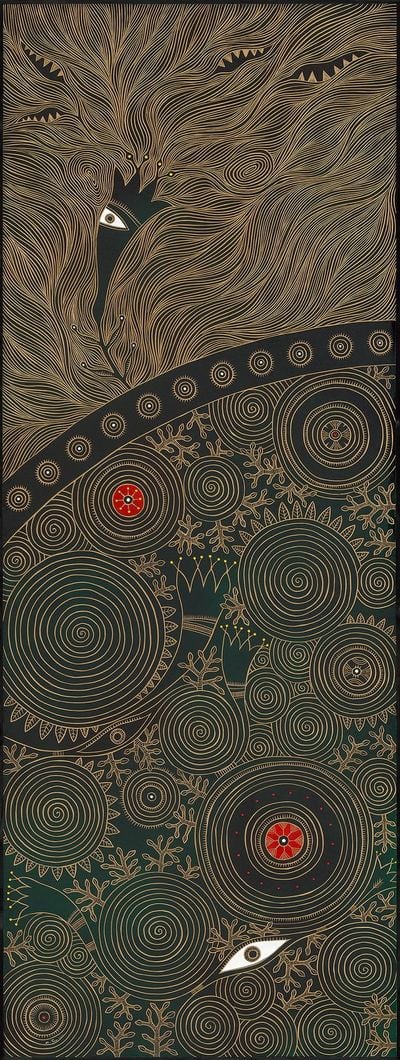

Using a selective palette of white, vermillion, and emerald on dark ground, etched lines show the grain of the planks underneath in the pair I found a field in the mountain of my spirit (I) and (II) (both 2021), depicting stylised vegetation patterns, speculative eyes, and spiralling images of the sun that form a round, vivacious ground.

The artist usually uses a very limited set of deep colours inspired by traditional Paiwan crafts. The paintings in this show are connected by their black backgrounds, though the colour represents a stabilising force for the artist, rather than the despair with which the hue is often associated.

For Etan, black reminds him of dark stone slabs used for making houses or the colour of fired clay, communicating a material sense of reassuring endurance—comforting associations that are extended into My Sacred Mountain as a whole.

The show's opening was delayed due to Covid-19. Etan says that Paiwan language has a word for this type of obstacle: veljengu. In response, the exhibition's 12 new paintings were conceived as a poem for troubled times, with each title constituting a verse written by Etan.

But that invocation for hope resonates, too, in the earliest work in this exhibition. The round swirls and succulent vegetal branches on an emerald ground in Sweet Fragrant Mountain Winds (2020) refer to what Etan heard Paiwan elders say after their relocation from their ancestral lands after the 2009 Morakot typhoon: that the wind is sweeter at home.

Etan's mother passed away not long after the Morakot disaster. It was the beginning of an arduous period for the artist, when art became a way to recalibrate distress.

That recalibration is captured in I am free as I am (2021), with the artist appearing in profile amid a trinity of fish-shaped eyes, conjuring the oneiric ambience of someone at peace with themselves. —[O]