Hany Armanious at Southard Reid, London and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

The artist Hany Armanious, who represented Australia in 2011 at the Venice Biennale, is best known for creating sculptures through the method of casting with resin. The subjects of his casts are often everyday abandoned items we tend to overlook, his process transforming such objects into new constructions with possibly new meanings.

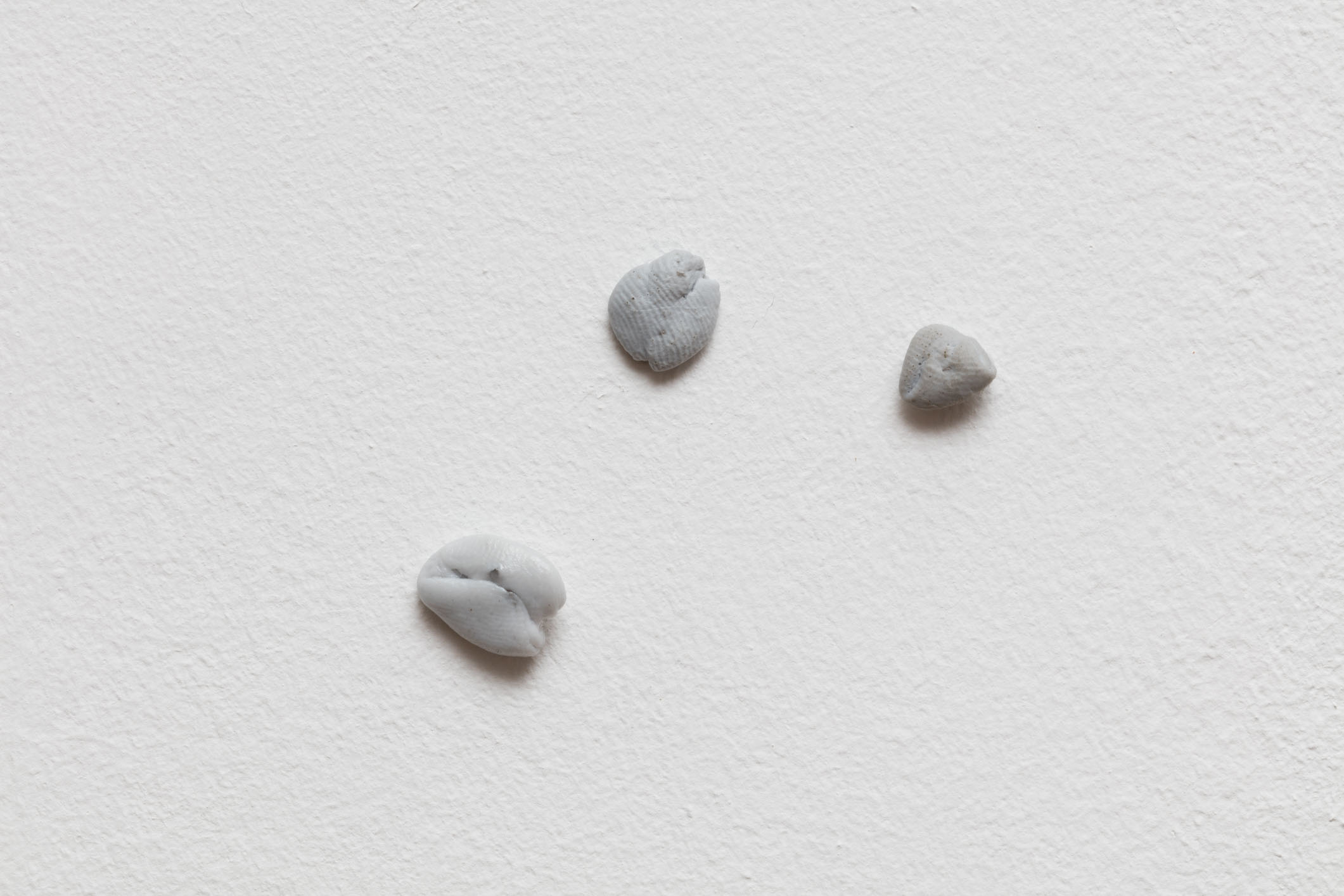

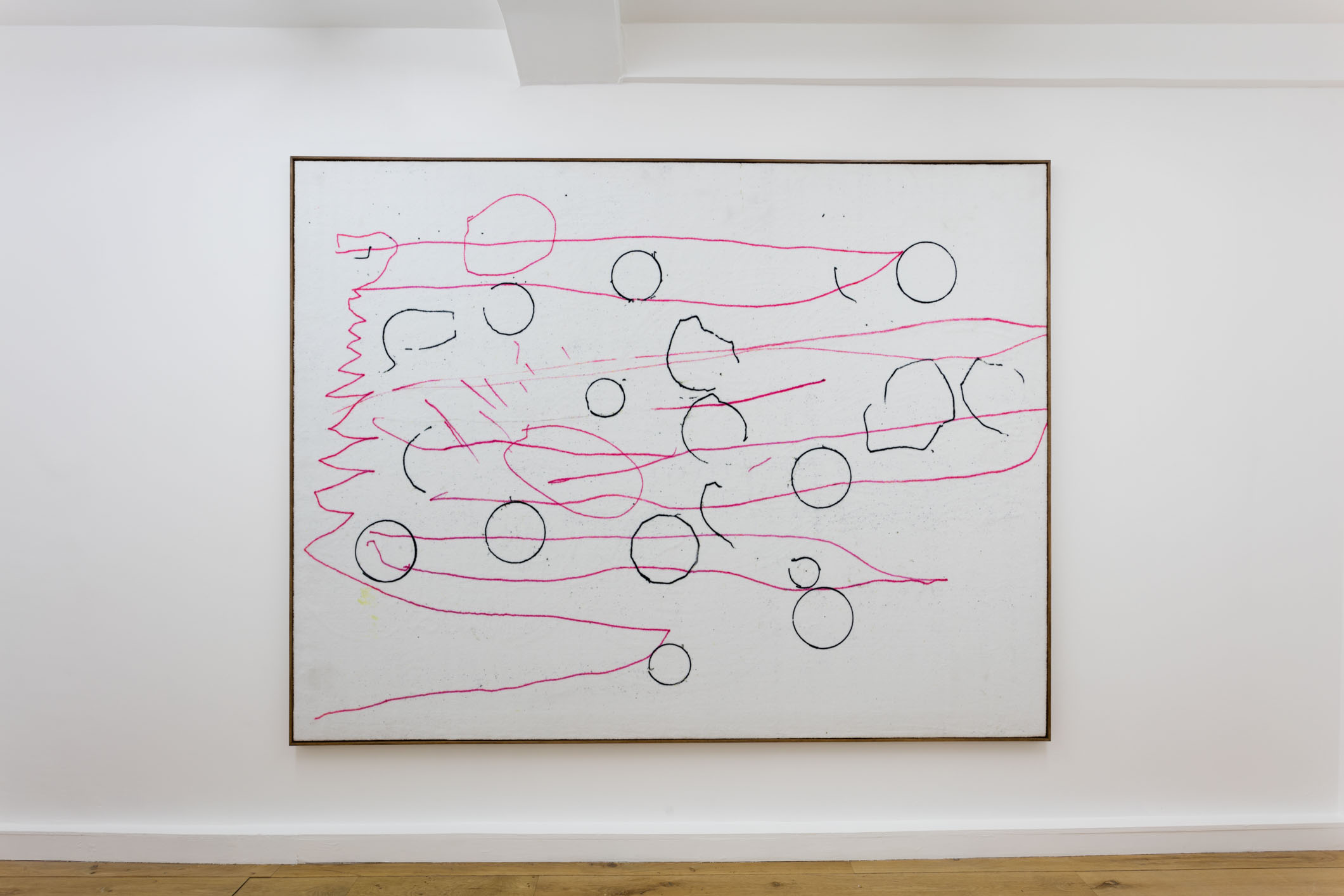

Currently the Egyptian-born Australian is exhibiting works at Southard Reid in London (until 21 May 2016) and at Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery in Sydney (until 30 April 2016). His works in London are from three recent series: a collection of cast Blu-Tack blobs, seemingly half-burnt house candles and a more recent group of ‘paintings’. The paintings comprise printed carpets hung on the gallery wall, with imagery taken from his four-year old son’s drawings.

At Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, the exhibition focuses on one body of work: the plinth pieces made between 2007-2012. These are described in the gallery’s press release as investigating themes of ‘elevations, legs, footings, impressions, and depressions; essentially anything that engages how we connect to the earth’. Ultimately both exhibitions require the viewer to engage directly with each work, requiring a re-look and a re-think.

Initiated by Ocula contributor, writer, curator and painter, Sherman Sam, here Armanious discusses his ideas on sculpture, his working method and choice of subject matter with painter, Clive Hodgson. Hodgson is an abstract painter based in London known for his sparse paintings that often use his name, signature or the date as a motif. He recently exhibited at White Columns in New York and Wilkinson Gallery in London, and will be showing a new group of paintings at Independent in Brussels with Tatjana Pieters.

SS: The first time I saw one of your objects I didn’t know it was a cast.

CH: It’s amazing when you get that it’s not the real thing. It’s odd that it’s a cast. How do you get the colour?

HA: I mix all the colours before I pour it. I pour one section first, then I pour the next one. I make little separators so they don’t leak into each other, but I have to let it set, then pour the next. It was a technique that I devised because I wanted to make these things. A lot has to do with the intensity of the colour that’s in the material itself. Because of that I think it has a lot more presence than the original object.

SS: Do you consider them representations? Or do you consider them facsimiles?

HA: I was about to say, it’s as if they’d been injected with extra life … souped-up.

SS: That’s a nice way of describing it.

CH: When you’re walking through the world and seeing things like these Styrofoam steps [referring to Wonder Wheel, 2009, featured in the catalogue for the 2011 Australian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale], or this vinyl back of a chair [referring to We Astrologers, 2010 also featured in the catalogue], did you recognise that that’s it?

HA: No, no, I don’t, I’m blind to it. They sort of impose themselves on me. You’re looking for the good stuff, not the bad stuff. You can’t seek it out. It literally blows into my field of vision, and you have to slow down enough to recognise its worth or you miss it! But that stuff's there all the time, it’s about adjusting. You can’t just go out and find it, is what I’m trying to say.

SS: Do you ever think, ‘Oh, I’d like to cast a piece of ...’, then you go out looking for it?

HA: Sometimes, I can’t remember what though. But often it’ll come with a real experience of the thing rather than a complete invention.

SS: Like?

HA: Like a piece of soap in the shower. It will get me thinking that’s an interesting colour and shape’, and then I’ll start keeping soaps to use for my collage.

CH: So is all of this colour added?

HA: The resin is clear, and then there are resin pigments that you mix in that are a liquid colour. It’s a kind of painting in 3-D. So something like that [points to Relative Nobody, 2010, a blue block with grainy, yellow fragments from a piece of chipboard] you have to mix this blue colour first then pour yellow-brown colour into each of those little fragments. That’s excruciating. You’re talking about a box with little molds and these invisible little depressions in it, which with a scalpel you’re dropping little drops of resin into. You can’t paint with resin, because it congeals. You actually have to pour it.

CH: The interesting thing is that it doesn’t actually have any sense of gesture.

HA: Exactly. It’s quite a mechanical activity.

SS: Do you have assistants helping you?

HA: I did have them when I had the budget. Often it takes me six to ten attempts to get it right. You don’t know how it’s going to work; you work it out as you go. This piece with chipboard [gestures to Relative Nobody, 2010] is an absolute nightmare to get done convincingly. Something like this, Interface (2011), which is a fabric divider screen, the mold is the big issue. You’ve got to get the mold right, and it’s made with liquid silicon. If anything is porous, the silicon will seep into it and you’ll never be able to separate them. So you have to calculate the thickness of how it penetrates and try to create a barrier so it doesn’t get absorbed; they are found objects and you don’t want to destroy them. So there’s a lot of reversal and preparation, so the object doesn’t get damaged when you pour your silicon. In fact that was quite an achievement to get a fabric so porous to get a mold out of that.

CH: When you stand them together, what’s the difference between the original and the work?

HA: I don’t do that, I’m not interested in comparing them. I only do it for colour.

CH: Seems to me that it has a different kind of aura.

HA: Definitely! I like to think it has more. It’s visually more pleasing. It doesn’t finally come to life until you pull it out of the mold. You’ve got the original, but it’s not until it’s made that you finally see it for the first time.

SS: And are the molds reusable?

HA: Yes, you can, but they get destroyed after they are cast once or twice.

SS: Is there a reason? Do you not edition?

HA: They are not meant to be multiples.

CH: You don’t go out looking for them but they blow into your way?

HA: They blow into me [laughs].

CH: Do you see a factor in what’s blowing into your vision?

HA: They are derelict in a way. Things that are crap, and the crappier, the better. It’s really hard to find that, the really crappy things.

CH: Is it to do with things that aren’t of value?

HA: ‘Invisible’ I think is the word, rather than ‘value’. I think ‘value’ is pretty even. Phillida Reid used ‘ruins’ earlier.

HA: Yes, that’s true. But when you really look at it, what’s not crappy? Is there something that’s really precious? There’s nothing that’s precious. And by the same token everything is precious.

CH: I think painting fustrates me. There’s a limited range of things. I look at pieces like yours, sculpture or other people’s work where they use an object or something …

HA: You think there’s more scope?

CH: No, but they have qualities that I’m envious of.

HA: You think painting has a limited set of qualities? I think painting is the hardest thing you could do because of those limitations. But when you transcend them, when a new thing is brought to the table, it’s so exciting. That’s why you chase it, because it is possible.

CH: For example, seeing objects in the world, like, Isa Genzken’s work at the Whitechapel Gallery, her pink, green resin things have a really great quality. She is great at using materials, and I’m jealous of that. When I go back to painting I can’t make that happen. So the challenge is to make something equivalent happen, but using paint.

HA: She’s having a ball! I think it’s possible [in painting], and when it does happen its so much more exciting than some transparent green stuff with a bit of resin poured into the corner of it.

CH: Yes, but maybe it is this in the position of objects that are in the world. A painting is in the position of a pseudo object, isn’t it? Partly on the wall and partly ...

HA: Yes, but it’s a complete illusory world, a window so to speak. And there’s all this suspension of disbelief, but when it’s working you don’t even have to try. It just takes you. You really have to have an eye for painting though and it does something to your eye. Do you agree?

CH: I quite like the idea that the painting is closer to some kind of sculptural idea rather than a window. That it resists being sucked backwards into the window. It’s sort of pushing outwards into the world.

HA: What does it say? It’s just speaking of its own or insisting on its own materiality? But even when it does that, there’s still this incredible visual illusion. That’s the beauty of it.

CH: Yes, that’s right. But don’t you think of yourself as a painter in another mode?

HA: I probably am, but I don’t bother trying to define myself. I’m really engaged with sculpture in terms of the stuff that I look at, but I don’t look at it too much. From the little I’ve seen of your work, it’s as if painting is such a vast arena but you’ve been able to define your own field, this could even be the letters in your name. At least you’ve found a structure to work with by introducing this limit, and that frees you up.

CH: Yes, but I always feel very restless about it.

HA: What’s the restlessness about?

CH: Because, in a way, I don’t want to have found something. I want to find something. I want to be mobile. I feel dissatisfied if I feel I’m stuck, I don’t like things to feel static or assumed.

HA: Where has that been? There’s no assumption or static, is there?

CH: It can happen if you feel that you make something familiar to you. That you sort of know the deal …

HA: Is it knowing? It doesn’t feel like that; it seems revelatory.

CH: That’s the moment that I’m interested in.

HA: You can see that! That’s when you recognise when something is working and when it’s not.

CH: Is there an equivalent moment for you when you see an object?

HA: I guess it’s a relationship with a them ... but also I don’t understand it when I start making it. These qualities make themselves felt. It’s quite intuitive why I choose something. A lot of it’s blind. I don’t have much of a clue.

CH: Is the material consistent? Is the process at all dangerous?

HA: Yes. I am worried about killing myself. It’s just the best, most durable, most light and fast material I can find. You can do anything with it, it's liquid glass basically. But it’s toxic, it’s expensive and it’s a very long process. You’ve basically got to fire the objects when they’re finished; put them in a kiln and fire them so they achieve their maximum exo-firm. This is so that they don’t melt or get soft on a hot day. It’s all about heat. They’ve got to be tempered, post-cured. And things can go wrong, when you put them in a kiln, they can sag and distort. This is after six weeks of a labour intensive nightmare, you put it in the oven...and surprise! It’s such a huge investment emotionally and financially.

SS: How often does it go wrong?

HA: Quite frequently … you’re not supposed to do that with resin. It’s for jewellery, not for kilos and kilos of …

SS: How did you find out about firing?

HA: This material has to be fired. It’s called post-curing.

CH: What was the first thing you ever made in resin?

HA: I was making replicas of polystyrene scraps, and the resin I first used was white, it wasn’t transparent. It just came off the shelf, and the only reason I started using it was that the resin was the same white as the polystyrene. Usually I use material that resembles the thing I’m trying to describe. So a lot of the stuff in bronze is describing something that’s cheap and yellow. Anything yellow or silvery, I use silver or gold. But at some point I would love to go beyond that, so that it doesn’t stay on the wonderment level … ‘how long did it take you to make that?’ That aspect of it worries me.

CH: I suppose there remains the fact that there isn’t any gesture in the process and you don’t have the material or the process to be the equivalent of the gesture. You just wind up with an object that has qualities that are inscrutable.

HA: Yes. They combine so that often there are configurations of objects. In it there is something that is a pretty simple method of ‘re-presenting’. I guess it gives you a license to play like a real idiot; you can be simple and dumb with it. It just allows you that space to play, to have serious fun!