Knives, spirit, and ink: Three artists of Taiwan

Taiwan doesn't have it easy when it comes to securing a position on the contemporary Asian art map. With gargantuan China and boomtown Hong Kong next door, interest has persistently swayed westward. However, whereas rapid modern change has seen many old artistic techniques swept to the side in Hong Kong and China, a league of artists in Taiwan are breathing new life into tradition as a means of keeping ties to the island nation's artistic identity. Chu Weibor, Li Chen and Pan Hsin-hua are three artists for whom tradition—whether it be in their subject matter, techniques, or materials—provides an entry point to new areas of artistic exploration and gives Taiwan's culture its undeniable richness.

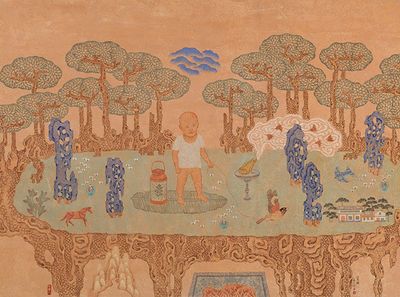

Pan Hsin-hua, Streaker: Flying a Bird (2016). Ink and colour, paper. Courtesy the artist and Asia Art Center, Taipei/Beijing.

An obligatory disclaimer to make in this first instance is that Chu Weibor (born 1929), the oldest of these three artists, isn't actually Taiwanese by birth—though considering his impact on the nation's art history, he may as well be. Born in Nanjing in 1929, Chu arrived on the island with the Kuomintang as it retreated from the Chinese Communist party in 1949. With a new life tainted by homesickness and military boredom, he turned to art as a form of distraction, but quickly realised it was more than a mere preoccupation. In 1958 he became a member of the Dongfan Art Group, also known as the Eastern Painting Association, led by Lee Chun-shan, who pushed the group's members to seek innovation in concepts, rather than technique, whilst staying true to Eastern philosophies.

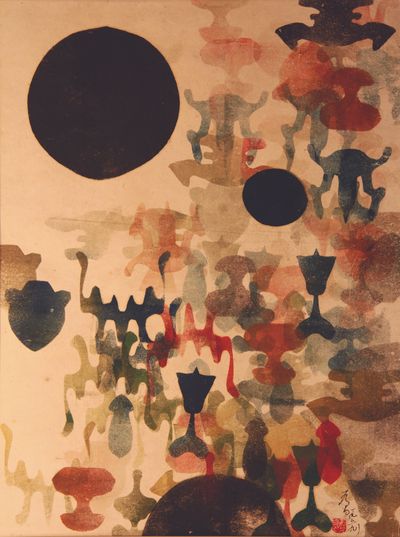

For Chu Weibor, this resulted in experimentations with a vast range of media—namely oil paint, house paint, ink, wood, and fabric—choreographed by a harmonious inner spirit that saw him glide effortlessly from one concept to the next. This harmony can be felt when speaking to Chu, who talks about his art and art making with calm conviction. He has the ability to find an essence in every material he uses, believing that 'art creation and the use of materials are limitless'. This he pushed furthest in the 1980s when he started taking a knife to canvas in Fontana-like fashion, slicing across the white to reveal a layer of red beneath, or black; calling to mind the concept of Yin and Yang. Some of these canvases avoid colour completely; emphasising his belief that blank space leaves more room for imagination.

Chu's brother, father and grandfather were all tailors, so his decision to employ the act of cutting in his work was somewhat a natural turn. The act of cutting dates to his earlier woodblock prints, in which aspects of traditional Chinese folk art are more evident. Many of these are of remarkable length, such as the two metre-long Wedding Procession in Bamboo Village (1977); an intricately detailed depiction of a bamboo village constructed entirely in his mind. This radical transition from traditional, folk forms of art to modernist ones is demonstrative of Chu's investment in Taiwan's modern art trajectory. Through different techniques, Chu explored how an artwork can morph around its material essence, opening up a plane upon which other artists could consider new approaches to a medium that may have become outdated. Chu still explores new forms of art making today, as can be seen in his thread series (1996-2015), or in his cotton bud series (2001-02), namely Display (2001) in which cotton buds are lined up in the centre of a black canvas and fall into one another in an undulating domino effect; an ode to his understanding of aesthetic potential in simple materials.

Of similar spiritual pursuit is Li Chen (born 1963), although in Li's case, pursuit has bestowed him with two immense warehouses in Taichung and Shanghai, and 20 production assistants. His signature sculptures of immense, voluminous figures with mischievous, baby-like faces have become a reference point in Asian contemporary art, and a favourite in global auction house sales. His works are celebrated for their technicality, and Li is quick to emphasise that sculpture is the most laborious of all media. In their finished state Li's sculptures seem weightless despite their size, and this effortless appearance is testimony to a painstaking technical process that takes place across his warehouses. Taiwan, he says, is not accustomed to sculpture as it is other media such as painting, and the works have to be sent to a more skilled workforce in Shanghai for the post-production phase. Li Chen's work has been subject to a number of international exhibitions, such as Eternity and Commoner at the Frye Art Museum in Seattle in 2012 and Journey of Solitary Existence at the Asia Art Centre in Beijing in 2014. However the spark of his international recognition came about in 2007 when he was invited to the 52nd Venice Biennale to hold his solo exhibition entitled Energy of Emptiness.

Just recently, his oeuvre was subject to a sizeable retrospective at MOCA in Tapei titled Being: In / Voluntary Drift (1 July-29 August 2017). Divided into chapters ranging from 'Arriving', 'Entering', 'Leaving' and 'Exiting', Li encouraged viewers to experience his sculptures as a spiritual journey, which felt unavoidably gimmicky when asked to slide down a fireman's pole in the last room, to return to the museum entrance; and supposedly one's enlightenment. The exhibition was less of a serious spiritual quest and more a playful presentation of Li's multifarious sculptural practice which included only a few of the aforementioned fat and glossy floating figures and more of his recent clay and wood sculptures that explore human nature's many sides. Exemplary of this is Butterfly Kingdom (1999), which was presented in the 'Entering' section of the exhibition in the first of the ground floor galleries. Standing legs splayed, this clay female figure's main feature is her 12 outspread arms, each expressing different gestures ranging from victory, to defiance, with a cheeky middle finger thrown in.

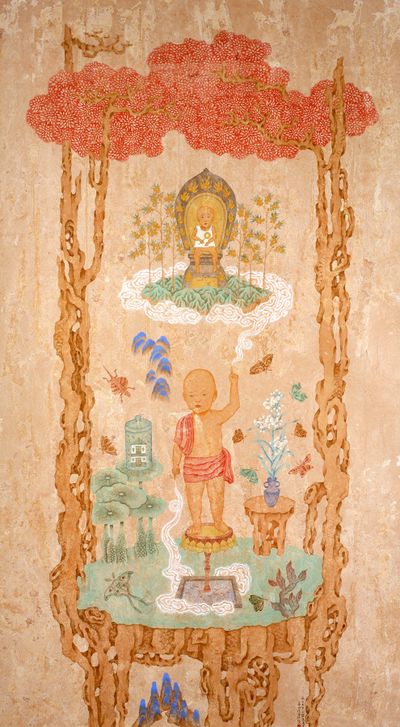

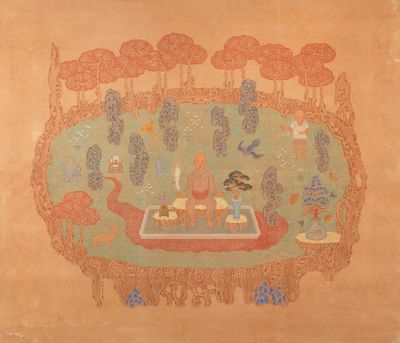

Pan Hsin-hua's intricately detailed ink paintings are quietly defiant. Like Chu Weibor, Pan acts on the rim of the market and puts technique and materials at centre stage. His specificity with materials, however, is akin to the rigueur of Li Chen. Pan has maintained a fidelity to pigments and paper in an artistic climate that has frequently plunged him into a state of self-doubt with regards to the contemporaneity of his medium, arguing that the capacity of ink has been undermined by an obsession with the medium's traditional attributes. Pan uses Hemp paper as an alternative to the traditional Xuan paper used by ink masters, upon which his paintings are rendered in 'mogu', or 'boneless' style, a traditional compositional technique in which perspective is absent, and forms seemingly float about the picture plane. It is a controlled floating, however, that makes Pan's works so exquisite.

Subjects drawn from the natural world such as dusty pastel moths, lotus leaves and flowers come together with the occasional cherub-like child to form playful and delicate scenes that border on surrealism, configured in a manner that resembles ancient maps or primitive art. Adding water to pigment in earthy tones, he builds the different parts of his paintings layer by layer, avoiding too much build-up of ink so as to retain the paper's texture. Of assistance here is the Hemp paper Pan uses, which comes from Puli, an urban township in Taiwan's Nantou County, and enables Pan's approach to colouring and contouring along with the application of Alum as a primer. The substance emphasises the earthy tones in his paintings, so that they mimic ancient murals. Forming a narrative or ascribing meaning becomes an irresistible urge to many who view his works, and Pan is often asked if the child figures have religious connotations. Yet he maintains that there is no particular meaning behind his subjects, that a good painting should be limitless in its interpretations, and that at times he adds elements such as critters or plants simply to provide compositional balance.

Pan's works have been included in many ink related exhibitions in Taiwan, such as Form Idea Essence Rhythm: New Aspects of Contemporary East Asian Ink Painting at Taipei Fine Arts Museum (2009) and the current exhibition titled Memories Overlapped and Interwoven: Post-Martial Law Period Ink Painting in Taiwan at the National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts in Taichung (7 August-8 October 2017). His works have also been exhibited at Michael Goedhuis' gallery in both London and New York, and is currently being celebrated in a solo exhibition at Asia Art Center in Taipei entitled Arcadia Curiosities (30 September-5 November 2017); an excellent entry point into the richness of Taiwanese art. —[O]