Patricia Piccinini: Inside the Artist’s Melbourne Studio

In a video interview, Piccinini discusses her strategy of winning us over with category-defying creatures that valorise care.

Known for hyper-realistic silicone sculptures of hyper-imaginative creatures, Patricia Piccinini is among Australia's greatest living artists. She represented the country at the 50th Venice Biennale in 2003, and frequently exhibits at institutions around the globe.

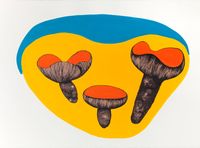

Among her most spectacular undertakings is the creation of hot air balloons called Skywhales—giant imaginary beasts who evolved to live in the atmosphere—and the exhibition A Miracle Constantly Repeating, which took place in the long-abandoned ballroom of Melbourne's Flinders Street Station in 2021.

Piccinini invited Ocula Magazine's Sam Gaskin to visit her studio in November 2022, when she was preparing to share new works at Singapore Art Week alongside her exhibition We Are Connected (5 August 2022–29 January 2023) at the city's ArtScience Museum.

Patricia Piccinini was born in Sierra Leone in 1965. She also spent several years in Italy before moving to Australia at the age of seven.

'My migrant experiences really informed the kind of person I am, the kind of artist I am,' she says. 'When I came here, I really did feel welcomed, but I didn't really fit in. I had to really adapt and change to be part of this community, and I did that because I just wanted to feel safe.'

Consequently, she doesn't identify as an outsider.

'As an artist, I don't see myself as somebody who's on the outskirts of society, looking in and telling people about ourselves and what's right and wrong. I see myself—and I really want to see myself—as somebody who's inside and talking to other people about things that are important to all of us.'

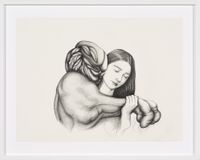

Building community and empathy for other people and animals, and even imaginary species, has been a major part of her practice.

'I think the overriding theme of my work of the last three decades has been how we as a society understand nature, as opposed to artifice,' she says. 'But within that there are some very strong themes around care. Like, what kinds of caring relationships are possible, and what do they look like? And I think this theme is very important when we think about the environment.'

'What kind of a relationship can we have with nature, when we've come to this point where we're in a real crisis?'

Environmentalists often use charismatic megafauna—creatures such as pandas, elephants, tigers, and whales—in their appeals, but Piccinini doesn't always make it so easy for us to align with nature.

'In my work, I do ask people to go on an emotional journey from aversion to care. And the way I try to achieve that is, I make a scenario or proposition, an artwork, a sculpture, that has something in it that is sort of repugnant or repulsive, and it pushes you away. And then there's something in it that pulls you in, on an emotional level, an ethical level, or an intellectual level.'

How does she get people to re-engage with a being they might initially see as repulsive?

'Often, it's because we see a kind of a set of values that we're interested in. And those values could be around connection, around care,' she says.

'I'm interested in valorising values like care, and I don't feel self-conscious about it anymore,' she says, 'because if we don't care, for things like children, like for the environment, things just collapse.'

'You can walk through a museum, and there'll be no images of mothers and children or families, fathers and children. But that's a pivotal and important part of every homo sapiens' life. Our brains rely on that.'

'I think it's up to people like artists to validate care as a value, because we don't see it in other places,' Piccinini says. 'We don't see it very much in politics. We don't see it in so many different places.' —[O]