Points of Departure at Lehmann Maupin, Hong Kong

Summer is the time for gallery group shows, a filling up of the white cube with dead stock. They're usually a pretty boring mind-numbing affair of recycled work from previous shows tied together with a spurious curatorial spin printed on a press release that nobody will read. The collectors—along with the gallery director—are still chilling on their yoga retreat in Ibiza.

Installation view: Points of Departure, Lehmann Maupin, Hong Kong (20 July–9 September 2017). Courtesy the artists and Lehmann Maupin, New York/Hong Kong. Photo: Kitmin Lee.

I expected much of the same visual filler from the summer show at Lehmann Maupin of work by three contemporary Chinese artists. Fortunately, I was surprised and ended up spending more than the requisite ten minutes such summer group shows usually take up. Twelve paintings, by Xie Nanxing, Lu Song, and Gao Ludi, are brought together for this particular show (20 July–9 September 2017). The artists take pre-existing found images as their 'points of departure', drawing on appropriation-based processes of American artists in the 1980s like Claes Oldenburg and Robert Rauschenberg who reproduced, juxtaposed, repeated and distorted images sourced from popular culture.

The works owe much to the importance of digital media and the Internet in shaping our understanding of the world. These artists—born in the 1970s, 80s, and 90s respectively—are very much a product of their time, their work process echoing the ubiquitous reproduction of images in a media-saturated culture.

The youngest artist in the show, 27-year-old Gao Ludi presents eight works including two large abstract paintings, which explore the historical relationship between photography and painting, and occupy a liminal space between the virtual and the physical. His portraits and abstracted images of nature and natural phenomenon are composed of superimposed layers of shapes and colour. Working with found online images Gao Ludi layers, sprays, stencils, dribbles, scrapes back and rubs out the paint on his canvases until they are bright, colourful surfaces of graphic geometric compositions.

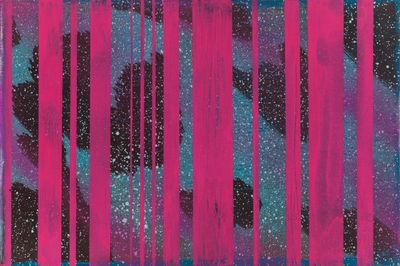

The speckling and phosphorescence of TT-11 (2015) calls to mind an interstellar scene. Violent magenta streaks skewering the image resemble violent lines of white (fluoro) noise interrupting a satellite image transmission. Dusk (2017), the largest in the series, recalls the hazy glow of sunrise with flat slices of muted oranges and pinks cutting vertically and diagonally across the large canvas. The scale and perspective allows the work to wrap around the viewer, enveloping them in its colour. Flower (2015–16), a smaller painting by the artist, depicts white tulips which resemble paper cut outs glued onto a green canvas.

Lu Song's paintings are a distillation of photographs the artist has taken of landscapes. The image is repeatedly layered until it becomes a hazy impression of the original, like a distant memory. His two paintings of leafy branches skirt the line between representation and abstraction. The artist applies free and loose brushstrokes in a multitude of layers, full of movement and life, with washes and dabs of colour in sketchy strokes recalling atmospheric conditions. Titled Swaying 1 and Swaying 2 (both 2017), the paintings give the illusion of movement, of a breeze, and the dappling of sunlight through leaves.

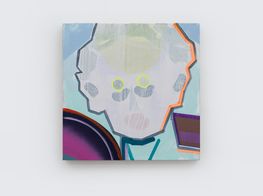

Xie Nanxing's expressive oil sketches also underline an interest in obfuscation and distortion rather than representation. Two colourful paintings—one orange, the other blue—hang in the gallery's side room. On first glance the paintings, a mess of wet splotches, look like paintings of flowers. The full image cannot be deciphered standing up close to the canvas. Distance is required, or a lens. The image comes into clearer focus through the lens of my iPhone camera. The orange painting, Untitled No. 2 (2017) reveals itself as an image of four female nudes smoking; the blue painting, Untitled No. 1 (2017) is unveiled as a scene in a casino, hinted at by the playing card in the bottom right hand corner and the digital time stamp that suggests surveillance footage.

There is a tension between the figurative and the abstract in Xie's work. Traces and marks made on the canvas result in an abstraction of the original image. Leaving no room for narrative, they redirect focus towards the actual painting; to its surface, layers, and texture. The more that is obvious in a painting, the less you want to look at it. Like Lu Song, Xie Nanxing is more interested in the relationship between painting, space, and the object, and the relationship of the viewer to the painting, rather than just the static representation of objects.

These three artists manipulate the language of painting, flitting between the material and the conceptual. Images are built up upon canvases which are layered with paint, in a repetition of image and gesture, resulting in a distortion or abstraction of the source image. The imagery in the works is so reductive of the original that for the more abstract paintings it's difficult to relate it to its original source. In mass media, the original image is repeated and replicated until it is removed from its context. Likewise, the artists here have repeated the image until it is no longer recognisable. These artists' processes of superimposing and layering images mimic the way in which we consume images through technology—with speed and voracity. A cursory glance will bear little fruit. These works require time and engagement.

Their work is as much about looking and reacting as it is about the process. Unlike the images from which they are sourced—many disposable and requiring a nanosecond of our attention—the paintings require stillness and engagement from the viewer. Rather than becoming just a 'second hand truth', a simulacra; reduced, edited and worn, these works become their own truth. They aim to be more than mere representations. They are not replicas of reality—they are too far removed, too distorted to make a pretense at being the real thing—but they do convey a conceptual truth about our time.

French philosopher Jean Baudrillard states, 'We live in a world where there is more and more information, and less and less meaning.' These three artists have all appropriated and layered imagery, but they have also stripped away information and detail from their images, abstracting them in order to allow the viewer space to import meaning, to look hard and see what may otherwise be invisible. These works escape the reality and context of the original image to provide a point of departure for a dialogue on our image saturated culture and our relationship to it. —[O]