The Iconic Art of Lygia Pape

Sponsored Content| Projeto Lygia Pape

Concurrent exhibitions at the Art Institute of Chicago and Punta della Dogana in Venice frame the early and late edges of Brazilian artist Lygia Pape's diverse career.

Lygia Pape, Ttéia 1, C (2003–2017). Exhibition view: Group exhibition, Icônes, Punta della Dogana, Venice (2 April–26 November 2023). Courtesy Projeto Lygia Pape.

In Venice, the group exhibition Icônes (2 April–26 November 2023) features a Pape sculpture from the artist's later years. A simultaneous solo presentation in Chicago, Tecelares (11 February–5 June 2023) offers an expansive view into Pape's 'Tecelares' (Weavings) series (1952–1960), woodblock prints contextualising the work the artist would arrive to nearly 50 years later.

Pape was born between the wars in Nova Friburgo, Brazil, a small, mountainous municipality. Though she completed tertiary degrees in philosophy, she began informal artistic studies at Rio de Janeiro's Museu de Arte Moderna in the 1950s.

There, against the backdrop of post-war Brazil's rapid industrialisation, Pape connected with other artists such as Hélio Oiticica and Ivan Serpa. In 1954, the three—along with Aluisio Carvão and Lygia Clark—co-founded Grupo Frente. Led by Serpa, the group formed a vision of Brazilian art that rejected figuration and explicit politics in favour of rationalist principles, developing an approach that eliminates personal gestures through the application of rigorous industrial techniques.

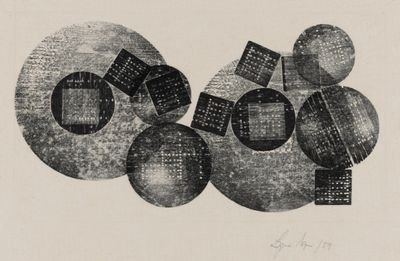

Pape took an early interest in geometric abstraction, beginning her work on the 'Tecelares' series two years before the Grupo Frente period. In one woodblock print from 1952, Pape printed different shapes with the same block seven times. With every round, different sections of the wood are masked off to build forms that evolve from and crash into each other.

The sense of movement found in 'Tecelares' would become integral to Pape's later sculptures and participatory works. Visual rhythm reaches its final form in Ttéia 1, C (2003–2017), which takes centre stage in Punta della Dogana's atrium. The installation's golden wires are stretched taut between a low-to-the-ground podium and the ceiling.

Depending on the surrounding light and viewers' movements, shimmering lines reveal themselves individually or at once before fading into the background. Cascading from the ceiling, they outline sets of squares on the ground, recalling the rays of the Statua della Fortuna (Statue of Fortune) perched atop the 17th-century building. As the Fortune weathervane turns, so might the rays.

Pushing against Grupo Frente's objective utopia, in which the purest handmade form leaves no trace of the hand, Pape became part of the splinter Neo-Concrete movement in 1959.

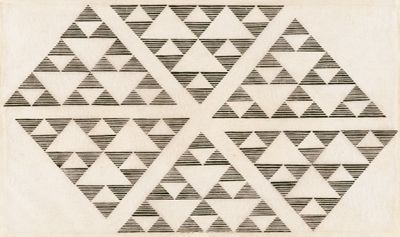

In general, Neo-Concretists carried Grupo Frente's geometric abstraction towards a subjectivity that encouraged meaning and poetry to seep into the work. The poetry of the 'Tecelares', which became bolder as Pape gained experience and confidence, is held in the relationship between the rolling lines of the wood grain and the sharp edges of the blocks from which they are printed.

In one 1959 monochromatic print of tumbling circles and squares, the printed forms recall both man-made projects—such as urban plans—and the tiniest particles from which man himself is made.

Each Tecelar (Weaving) builds what Pape once described as 'magnetised space', in which the negative area of a print remains active as a plane of shape, colour, and movement that brings together and activates surrounding forms.

In a 1955 Tecelar (Weaving), the spaces between the stacks of triangles made from horizontal lines become triangles themselves. In Ttéia 1, C too, the negative space between the lines becomes an energetic buzz, at once part of a solid plan and its own discrete element.

Pape's early woodblock prints were not always called 'Tecelares'. Before the late 1970s, they were presented as simply Xilogravuras (Woodcuts). Taking the Portuguese tecer, which means 'to weave', Pape invented the term Tecelares (Weavings) to allude to her haptic approach to printmaking.

The change reflects Pape's recognition of the resonance of the 'Tecelares' prints in her later work, many of which interlace small units into a multi-faceted whole. Divisor (Divider) (1968), one of Pape's most well-known performances, achieved this with human bodies.

Participants pulled their heads through holes in a sizable sheet of white fabric and marched on the streets of Rio de Janeiro resembling a many-headed entity—a visualisation of society as individuals woven together in a given space.

Pape wove with metal wire and thread in later sculptures like Ttéia 1, C, in which thin, golden rays cascade at angles from the ceiling to the floor. While constructed more than 40 years after the Tecelar prints from the 50's, there remains a through-line of movement rendered with each wire line and the haloes of fleeting light they collectively form.

Pape's sculptural works are the accumulation of her artistic phases—from the formal precision of Grupo Frente and the poetry of Neo-Concretism to the expressive urgency of an extreme social/political climate. They bring together the sense of scale, soft monumentality, and sensitivity to viewers' positionality of her later work with the movement and materiality honed in her earliest static forms.

In 2003, Pape said, 'I want to work with a poetic state, intensely.' Though she would pass away in Rio de Janeiro the next year, the same poetry, energy, and technical precision that underpinned her practice continue to resonate with audiences in Venice, Chicago, and beyond.—[O]