Shanghai’s Chronus Art Center Shows Art Coded for Hard Times

With over half the global population now under full or partial lockdown, smartphone use seems to be on the rise without there being any corresponding increase in feelings of connectedness.

Evan Roth, n22.230210e113.940187.hk (2017). Courtesy the artist.

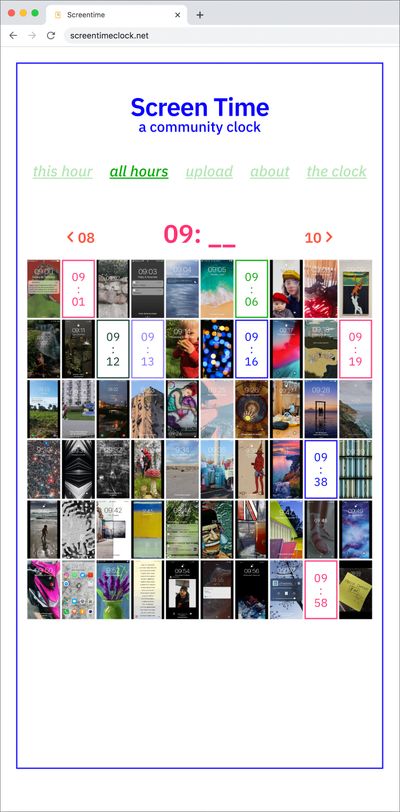

Helmut Smits' Screen Time (2019–2020) tries to bring together at least 1,440 of us, one for each minute of the day, by asking people to submit photos of their smartphone lock screens with the time displayed. The resulting online clock is still being built minute by minute, and offers the small intimacy of knowing that each image flashes before its contributor throughout the day.

The theme of connectedness recurs again and again in We=Link: Ten Easy Pieces, an online exhibition that counts Screen Time among its works. Organised by Chronus Art Center (Shanghai) and co-commissioned by Art Center Nabi (Seoul) and Rhizome of the New Museum (New York), the exhibition went live on 30 March, with ten works curated by Zhang Ga and hosted on sites that are accessed via hyperlinks hidden in the exhibition's main page. Scrolling down to read the exhibition introduction reveals ten circles, each representing a different work.

One of these is n22.230210e113.940187.hk (2017) by Evan Roth, whose title refers to the coordinates of a site in Hong Kong where submarine internet cables meet land. The website displays footage from a live webcam that looks up through the leaves of trees using an infrared camera—a nod to the frequency at which data travels along fibre-optic cables.

The image of white leaves stirring on deep red branches backed by a pink sky is otherworldly but lovely, evocative of cherry blossoms. A visit to the website, which involves signals from your device physically arriving at the location depicted, feels like a kind of hanami: the spring tradition of making a trip to sit beneath the cherry blossoms.

Not every piece in We=Link is as sweet as Roth's and Smits', however. Tega Brain and Sam Lavigne's Get Well Soon! (2020) is an e-card containing over 200,000 unique messages of well-wishes sourced from crowdsourcing website GoFundMe. The messages, which are depicted in small black sans serif on a white background, run across dozens and dozens of columns, each requiring vigorous scrolling before reaching the end.

In an accompanying essay, Johanna Hedva emphasises that 'The language of illness is a language of platitudes.' It is the number and repetitiveness of the messages that reveals an illness incubating beneath all this healthy goodwill. For the artists, Get Well Soon 'is an archive that should not exist'—an indictment of government healthcare systems that systematically fail to provide for their citizens.

In the absence of the white cube, which for all its inadequacies creates space for contemplation, online artworks must compete with chat messages and spikes in the wind, and the urgent desire to snack, check the stock market, or take one's laptop into another room.

Yangachi's eGovernment.or.kr (2003, remade in 2019) is another work that critiques government, not for under-serving people but for over-reaching. 'Information determines national competitiveness in the digital age,' the website declares, before garnering permissions such as, 'You welcome your eGovernment. Choose yes or no.'

Users are asked to input various details, including their name, names of their parents, hobbies, and incomes—the requests keep coming without any indication as to how such details might benefit the site, facilitate what it provides, or whether that information will be protected. What builds is a growing suspicion of exploitation.

While eGovernment.or.kr's efficacy comes from its verisimilitude to daily internet use—we've all given away similar information to countless websites—the satire in Headlines (2020) by Slime Engine (Li Hanwei, Liu Shuzhen, and Fang Yang) is more outlandish. 'A Good Outbreak?' reads the headline of their fictional digital tabloid as animated red mist descends on a Chinese mega city.

The 'hookvirus' the site refers to is fictional, but the attempts to spin it are very much in line with Chinese propaganda after Covid-19—suggestions that the virus has 'multiple origins co-existing around the world,' for example. The other content on the Headlines site is frenetic: a VR eight-lane highway suddenly overwhelmed by green smoke and a blue-haired anime girl in a micro-bikini performing 'new century fat reducing rave gymnastics' at home, for instance; and a row of animated zombies—the kind that appear in countless mobile games—queuing for a 'Chinese saviour crepe'.

Rendered in an aesthetic that amounts to unadulterated internet id, and without any apparent values of its own, Headlines is exhausting—a trait shared by Ye Funa's Dr. Corona Online (2020), a chatbot whose garbled replies to questions about the virus are derived from news headlines, social media, and motivational quotes.

The same can be said of Li Weiyi's The Ongoing Moment (2020), an online quiz based on a selection of arbitrary 3D shapes that rewards you with a 3D 'filter'—an augmented reality adornment, such as a double dumpling head or pastel-coloured rings and crab claws. The work seems grounded in little more than narcissistic nihilism, playful but also mechanistic in its imitation of products built by Instagram, Snow, and Snapchat.

In the absence of the white cube, which for all its inadequacies creates space for contemplation, online artworks must compete with chat messages and spikes in the wind, and the urgent desire to snack, check the stock market, or take one's laptop into another room. If nothing else, this creates a new metric for their success.

Take JODI's ICTI.ME (2020), a crash test dummy palette of yellow with black and white circles that takes you to glitchy code blinking fast, burning a halo into the screen like the corona of a solar eclipse. Is the work something you share with your own community? Does it make a connection? —[O]