It’s Peter Hujar’s Day

On 18 December 1974, Linda Rosenkrantz asked photographer Peter Hujar to write down everything he did on that winter's day.

Hujar had forgotten about this exercise, and before arriving at her apartment on 94th Street the following morning, he found himself hastily scribbling down everything he could remember.

'And luckily for all of us,' Rosenkrantz wrote in the preface of her book Peter Hujar's Day (2022), 'his day was filled perhaps even more than usual with interaction with people seen now as cultural icons, encompassing all the worlds Peter moved in.'

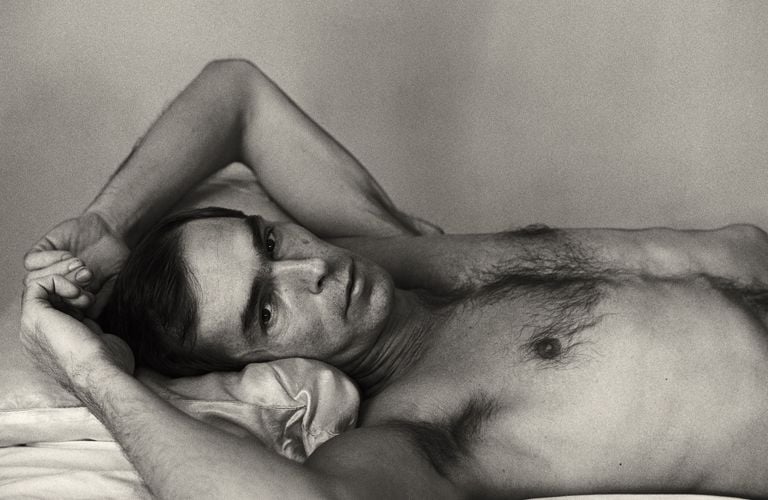

Legends of New York's downtown scene of the late 1960s—including Susan Sontag, Paul Thek, and Fran Lebowitz—drift in and out of the text. They were, after all, regular fixtures in his unflinchingly intimate portraits, which he shot in black-and-white on square format film.

Hujar photographed them and countless others—the writers, artists, dancers, and drag performers that he surrounded himself with while documenting the city's queer avantgarde scene in the thick of the AIDs epidemic. In 1987, at just 53, Hujar himself died of the disease.

Largely underrepresented by museums and galleries in his lifetime, shadowed by the likes of Diane Arbus, Nan Goldin, and Robert Mapplethorpe, Hujar will now be celebrated with solo exhibitions on both sides of the equator this month.

In São Paulo, the team at Mendes Wood DM hand-picked 14 photographs from The Peter Hujar Foundation in New York to present at the gallery's curatorial off-site space, Casa Iramaia, in the Jardins neighbourhood from 6 April to 4 May 2024.

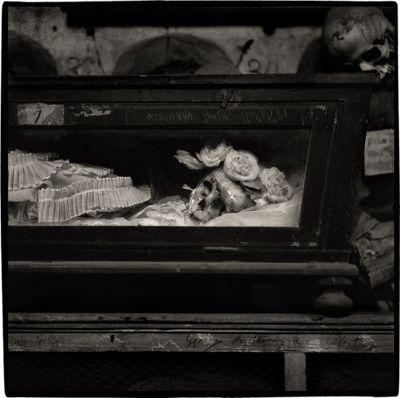

Meanwhile in Venice, The Peter Hujar Foundation is exhibiting the complete set of 41 photographs from the artist's 1976 publication Portraits in Life and Death—a memento mori of the artist's friends and fellow artists. The exhibition will be on view at Santa Maria della Pietà from 20 April to 24 November 2024.

Portraits in Life and Death (1976) is the only book of Hujar's work published in his lifetime. In 1963, he took a trip to Sicily with his lover and fellow artist Paul Thek, photographing the decomposing human forms in the ancient catacombs in the Capuchin monastery of the capital, Palermo.

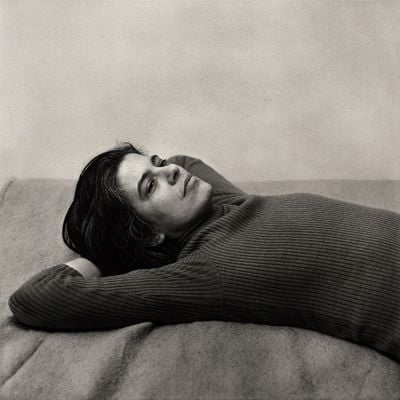

The 11 photographs that he included in the publication are accompanied by portraits of Hujar's friends—including Thek (Paul Thek, 1975), the American writer William Burroughs (William Burroughs, Reclining, 1975), and drag queen and actress Divine (Divine, 1975).

Introducing the publication, Susan Sontag wrote, 'Peter Hujar knows that portraits in life are always, also, portraits in death.' She continues, 'I am moved by the purity and delicacy of his intentions.'

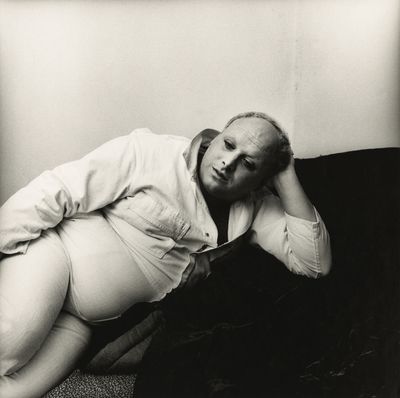

This duality of life and death is no better seen than in Hujar's 1973 portrait of Warhol's Factory-regular Candy Darling, on view in São Paulo, lying on her hospital bed where she was dying of lymphoma.

Tangled in white bed sheets, Darling gazes at Hujar's camera, a robust steeliness shining through her mascara-laden eyes. A bunch of white flowers—likely chrysanthemums, a flower signifying longevity and joy—sit beside her. Exhaustion and vulnerability shine through too. Hujar had a unique ability to go beyond the surface—the fragile dying body—to the character, the determination, beneath.

In introducing Rosenkrantz's book, Stephen Koch wrote, 'If you are reading in search of clues to Hujar the artist, notice how he makes you see what he's describing, and how he observes with his cool, quiet confidence.'

Throughout the book, there are many such examples. Hujar introduces details so trivial yet tangible that you can't quite believe that this was an exercise of memory.

Recalling a trip to Jade Mountain, a Chinese restaurant in New York's East Village, to grab takeaways for him and his friend, the curator and writer, Vince Aletti, Hujar recounts:

'There's a guy there who looks sort of fat but has a very nice face. There's something sort of lonely and strange—he looks very much like an unmarried man, straight, of 35. He takes out a felt-tipped pen and he starts to draw on it, he marks sort of squares. He was waiting for his order, which was chicken chow mein.'

'And then the waiter comes out of the kitchen, he says your order is ready and the guy sort of nods but continues drawing. Enough time has passed and he is still drawing these boxes. He's really into it. So the waiter stands there, sort of perplexed, and then he walks back over to him and says oh! It was three dollars and forty-five cents. And he leaves. Mine takes another few minutes and mine is $7.30, 7.43.'

This complicated account of simply picking up Chinese food is an inversion of how Hujar saw his photography practice.

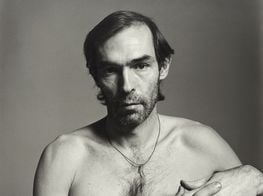

'I make uncomplicated, direct photographs of complicated, difficult subjects,' Hujar wrote. 'I photograph those who push themselves to any extreme, and people who cling to the freedom to be themselves.'

It's a freedom Hujar himself clung to, turning down shows on the basis that '[he'd] rather not let any shit out.'

'Peter was known and notorious in the downtown scene and cut a striking figure by all accounts,' recounts Hujar's London gallerist Maureen Paley.

'But he was given to self-sabotage and was frustrated by lack of interest in his work which is now being finally and more fully recognised posthumously.'

Main image: Peter Hujar, Self-Portrait Lying Down (1975). © The Peter Hujar Archive/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.