Antonio Dias was a Brazilian artist recognised for his vast body of often politically charged, conceptual artworks that traverse figuration and abstraction.

Read MoreDias' early works are characterised by graphic, cartoonish imagery, which was reminiscent of Brazilian cordel literature and playing cards. References to violence also feature widely in his works, such as in the painting Querida, você está bem? (Darling, are you Alright?) (1964), in which amorphous and abstracted human bodies seem to exhale smoke or blood. In his conversation with Ocula Magazine in 2018, art historian and critic Paulo Sérgio Duarte—curator of Tazibao and other works, Dias' 2018 retrospective at Galeria Nara Roesler in São Paulo—explained that the artist's graphic imagery was in response to the political climate of the time, notably the outset of a military regime in Brazil in 1964. Dias used body parts to allude to political concerns, replacing, for example, the nuclear mushroom with male genitalia, a recurring motif in his oeuvre. In Acidente no Jogo (1964), a red phallus protrudes from a black box alongside a white bone and a red clover-like form with a skull painted on it.

In 1966, Dias left his country and settled in Paris. He relocated to Milan two years later, where he met artists associated with the Arte Povera movement—among them Luciano Fabro and Giulio Paolini—and turned away from figuration towards a narrower palette and more conceptual works. His series 'Illustration of Art' (1971–1978), for example, encompasses paintings, installations, sculptures and films. In The Illustration of Art I (1971)—one of the silent films made with a Super 8 camera—two bandages cross over wounded skin until it heals. During this period, Dias also began printing letters on often monochromatic, gridded paintings, giving them titles such as The Prison (1968) and Occupied Country (1971) to reflect his experiences of living in self-imposed exile.

Between 1977 and 1978, Dias spent five months in a remote village in Nepal learning the traditional Nepalese craft of papermaking. Created by mixing materials such as soot, clay and iron oxide with paper, his new medium generated soft, muted colours and texture that signalled yet another stylistic shift in the artist's work. In The Illustration of Art / Tool & Work (1972), a pair of handmade papers show the handprints of Dias and a local.

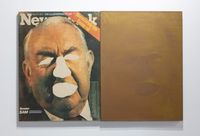

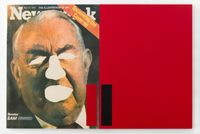

In the 1990s, Dias resumed working with a brighter colour palette and painterly form, with the addition of metallic pigments. He began arranging canvases and small objects into sculptural compositions such as in Cranks (1999), which comprises two canvases—one copper leaf and the other painted in red—flanking a larger grey painting like a pair of ears. Two elongated and phallic rods dangle from the bottom of the central canvas, adding a whimsical quality to the work. In Untitled (2011)—a row of three large canvases of the same size with two smaller paintings mounted on them—the abstract, swirling pattern of the red painting is in a permanent state of tension with the grid patterns that surround it.

Dias' work has often been associated with the Pop art movement. Dias agreed to show his work in the group exhibitions International Pop at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis and The World Goes Pop at Tate Modern, London, in 2015. However, in an interview with The New York Times in 2015, he stated: 'I always protest when I'm accused of being Pop—it's not my party', noting that he agreed to participate only because the shows promised to look again at the early 1960s. In his interview with Ocula Magazine, Duarte also noted that Dias' practice departed significantly not only from the lighter mood of American Pop art but also from the genre itself in that Dias never used ready-made commodities. He was exposed to the works of Brazilian avantgarde artists such as Hélio Oiticica, Lygia Clark and Lygia Pape, who were associated with Grupo Frente, a movement that rejected the then-prevalent nationalist tendencies in Brazilian modernist painting and concrete art, which advocated for the use of geometric forms and unmodulated colours and a dismissal of symbolic meaning. In the late 1960s, Dias also aligned with fellow Brazilian artists to partake in the tropicália movement, which sought to uncover the harsh realities under the increasingly autocratic Brazilian government and responded to the Nova Figuração (New Figuration) movement, becoming one of its leading proponents to revive figuration in art.

Dias' work has been exhibited internationally including at Sharjah Art Foundation (2018); Galeria Nara Roesler, São Paulo (2018, 2016); Beijing Minsheng Art Museum (2017); and Philadelphia Museum of Art (2016). His work is also in the collections of Fondazione Marconi, Milan; Museum of Modern Art, Rio de Janeiro; The Museum of Modern Art, New York; and Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo, among others.

Sherry Paik | Ocula | 2018