Once asserting that 'art is a guaranty of sanity', Louise Bourgeois considered art-making a cathartic process. Over her 80-year career, the French artist tackled themes of sexuality, desire, gender and the unconscious through prints, paintings, drawings, sculptures and installations. While she came to fame only during her 70s, she worked well into her 90s and has been hugely influential on subsequent generations of artists.

Read MoreInfluenced by psychoanalysis, Bourgeois' works are laden with her personal traumas. Born to a family of antique dealers in Paris in 1911 and having witnessed her mother's eventually fatal illness and father's infidelity at an early age, Bourgeois' childhood anxieties permeated her practice. Exemplary of this and made of several wooden planks resembling table legs, the formative sculpture The Blind Leading the Blind (1949) arose from Bourgeois' early memories of watching her parents while hiding beneath furniture.

Bourgeois studied art at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts and the Ecole du Louvre in Paris and in artists' studios in Montmartre and Montparnasse. Upon marrying the art historian Robert Goldwater in 1938, she moved to New York City, enrolled in the Art Students League and began making sculptures from wood found on her apartment building's roof. The body and feminism were revealed as concerns in these early works; made in response to her new role as wife and mother in America, the 1946–7 series of drawings and paintings 'Femme Maison', for example, depicts nude female bodies with their heads replaced by houses, signifying the stifling effects of domesticity.

Later sculptures made of wood, marble, bronze, plaster and latex are overtly sexual. The bronze and gold hanging sculpture Janus Fleuri (1968), for example, resembles a flaccid double-headed phallus, while the hanging male genitalia in the latex-and-plaster sculpture Filette (Sweeter Version) (1968–99) similarly points to Bourgeois' conception of masculinity as innately vulnerable. On the other hand, constructed from fabric, marble, steel, wood and glass, the sculpture Couple (2003) depicts the form of an embracing couple upon an oval base and overlain with a sheet of translucent pink fabric, resulting in an overall composition that resembles the labia. Similarly concerned with the female body, the 1991 rubber wall-relief Mamelles depicts 16 breasts arranged in a horizontal formation akin to a classical frieze; in 2001, the work was cast by Tate in fleshy, pink rubber—a material that emphasised its eroticism.

Across sculpture, painting and printmaking, such bulbous forms are a common motif in Bourgeois' works and often resemble egg sacs, phalluses, breasts and testicles. The white marble sculpture Cumul I (1968) depicts several spherical forms in various states of concealment under a sheet, while Bourgeois' installation The Destruction of the Father (1974) saw the artist cover a dining table with round, fleshy latex and plaster forms. Constructed as a way of expressing her anger over her father, the work is bathed in light emitted from red bulbs and laden with violence and resentment.

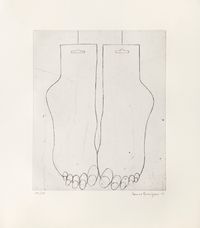

Hands too appear often in Bourgeois' work, representing touch, femininity and care. The bronze-cast sculpture Nature Study (1986) takes the form of a delicate, feminine-looking hand tied together with a small female figure by a tubular coil. Installed at the Jardin des Tuileries in Paris, the large-scale sculpture The Welcoming Hands (1996) depicts intertwined hands, cast in bronze and laid on five granite stones. While their touches are tender, the appendages are also severed at the forearms, suggesting disembodiment or loss. Other representations of the body were less literal but equally personal; the approximately 80 anthropomorphic, totem-like sculptures made of stacked wood that comprise the 'Personnages' series (1945–55), for example, were each inspired by a person Bourgeois knew.

After moving her studio from her Chelsea townhouse to a larger Brooklyn space in 1980, Bourgeois was free to create larger sculptures. It was there that she embarked on series of large-scale installation works that she called 'Cells', so named for their connotations of imprisonment and living organisms. Defying easy categorisation, these works have been described by art historian Julienne Lorz as sitting 'between a museal panorama, a theater set, an environment or installation'. Most often enclosed by wire cages or wood, 'Cells' such as Cell (The Last Climb) (2008) or Red Room (Child) (1994) contain sculptures and readymade objects such as spindles, needles and threads to stand in as abstract visual representations of traumas and bodily anxieties. Cell XXVI (2003), for example, comprises a large cage in which a bulbous form with human legs dangles in front of a mirror. Similarly, Cell XXV (The view of the world of the jealous wife) (2001) sees two ladies' dresses imprisoned in a cell—perhaps an oblique reference to her father's affair with the artist's childhood au pair and the pain inflicted on Bourgeois' sick mother.

It wasn't until 1994 that Bourgeois began the works for which she is perhaps best known: large-scale sculptures of spiders known as 'Mamans'. While she had been drawing the insects since at least the mid-1940s, it took 50 years for the motif to be realised as a metaphor for the mother figure. Instead of frightening or repulsive, Bourgeois considered spiders protective as they eat mosquitos and prevent disease. Furthermore, the webs the actual insects weave recalled Bourgeois own mother's work with tapestries before her premature death. These monumental spiders, which viewers can walk around and below, have been installed at the Brooklyn Museum, Tate Modern's Turbine Hall and the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa. Other notable public artworks include the fountain Father and Son (2005), installed at the Olympic Sculpture Park in Seattle. Comprising larger-than-life sculptures of a man and boy, the fountain's figures are obscured from one another as the water rises and falls—a direct reference to the troubled parent-child relationship that characterises much of Bourgeois' output.

Bourgeois' first museum retrospective was held in 1982 at The Museum of Modern Art in New York when the artist was 70. Since then, and following her death in New York at the age of 98, her work has been exhibited extensively in international institutions.

Ocula | 2019