Adriano Pedrosa's New Phase

Adriano Pedrosa.

Adriano Pedrosa.

Brazil-based Adriano Pedrosa is internationally recognised for his work as an independent curator, writer and editor.

In addition to co-curating two large and audacious exhibitions in Brazil last year, Mestizo Histories at Instituto Tomie Ohtake, São Paulo and Arte e Vida in Rio, Pedrosa was also co-curator of the 27th São Paulo Biennial (2006) and the 12th Istanbul Biennial (2011). He was curator of the 31st Panorama of Brazilian Art at MoMA in São Paulo (2009) and the Pampulha Museum in Belo Horizonte (2001–2003). Last November, Pedrosa took over as the artistic director for MASP [São Paulo Museum of Art].

As he embarks on this new phase, we spoke to him about the projects he has in store for the museum, its history, and the role of Lina Bo Bardi, who is responsible for the museum's renowned 1968 designed concrete and glass structure. Pedrosa is working hard to reinstate elements of Bo Bardi's original ideas that were based on the democratisation for showing and viewing art and architecture, which he believes have been rendered opaque over the years.

CBCould you briefly recap the first six months of your new tenure at MASP, in terms of your mission and projects for the museum?

APThere have been, of course, many different elements of this museum that needed to be revised and reoriented somehow, with a new programme not just for the exhibitions but also for the building and the institution, all the way from the different teams, to design and architecture. This is an institution founded in 1947, so there's a lot of history. My first impulse was to research, because I had never worked here.

Of course, I'd visited the museum—I live three blocks from here—but there's a very dense, layered, intricate history, so I tried and am still trying to read as much as possible on the architecture [by Lina Bo Bardi] and history of the institution and its exhibitions. Also, trying to immerse myself in the different collections; there are about 10,000 objects of different sorts. In a way, the first project that we did here, MASP in Process, which was a project that is still going on somehow, had an architectural component as well as an exhibition component. The architectural component consisted mostly of rediscovering and understanding the original architecture.

CBWere you exploring Lina's original intentions for the Museum?

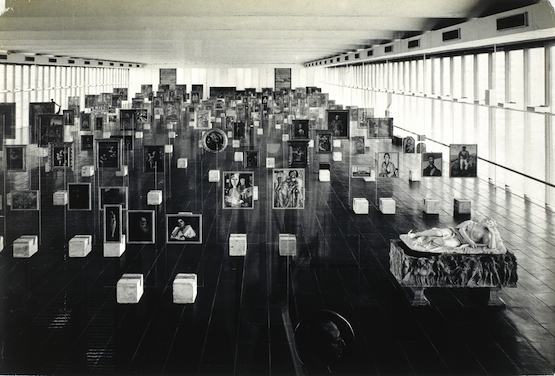

APYes, her intentions for the original project. For example, the first floor and two lower-level galleries were covered with drywall panels. In the lower level there is an original transparency [windows line it and it was open plan], because it's on a slope. The project there consisted in removing all the layers of drywall and a storage space in order to regain this transparency, with a view to the city, but also regaining the vitrines that divide the library and the restaurant from this gallery. This space is not easy, because it's huge and has no permanent walls. We were trying to understand the possibilities while maintaining this open space and thinking about exhibition displays that still maintain the transparency, that's why in the lower-level gallery we are now restaging the exhibition display that Lina Bo Bardi designed for MASP/FAAP in 1957/8—the museum was at Fundação Armando Alvares Penteado for a couple of years. She made this quite beautiful display that we are restaging for different exhibitions we are organising this year.

Going back to MASP in Process and the rediscovery of the original architecture, on the first floor, which has been subdivided into different rooms for the last 15 years, we took all this down and regained the open plan and on the first floor we'll bring in the exhibition display that was used at MASP when it was located at Rua Sete de Abril, in the 1950s. MASP came to Avenida Paulista in 1968. This has been a process of rediscovery and recuperation of the architecture. Even in the small details like reopening the stairway that goes from under the canopy to the first floor.

Transparency and permeability are two key concepts for the museum and the original programme of the architecture. The museum was built in suspension in order to preserve the view, because when the land was donated, the family that owned it demanded that the view be preserved. It is the largest freestanding space between beams.

CBI thought that came from Lina Bo Bardi. Was that their only demand?

APIt's the only one I've read about, it comes up a lot in the literature.

So, there is transparency there, in the glass façade, but I feel that also, in the recent history of the museum, this transparency had been rendered quite opaque and impenetrable in some ways. So this accessibility, permeability and transparency and, also, a democratic openness, are things that we are trying to work with a lot. The glass façade is complicated because of the light that can harm the paintings, but we are working on it and in October we want to bring back a key element, the glass easels [exhibition displays also by Bo Bardi] designed in 1957, but installed in the museum in 1968.

There is a classic image of a Picasso, The School Boy, on a glass easel in the Sete de Abril building.

CBSo they were already around that early?

APYes, she was studying them, but I am not sure she really used them then. I saw this image in Giancarlo Latorraca's Museu da Casa Brasileira exhibition catalogue [on Lina Bo Bardi's exhibition displays, in 2014].

Going back to MASP in Process, when I arrived at the museum, there was a Julian Schnabel exhibition in the two lower level galleries, and all the windows were covered up with panels, creating a huge white cube and also a photography exhibition. We wanted to start working on something as soon as possible, so when these came down and with the little knowledge we had of the collection, what we could do at that time was something process-based. At that time it was only myself and Tomas Toledo, a curatorial assistant. Since then we have two new assistant curators: Luiza Proença joined in January and Fernando Oliva in March. For this, we were going into the storage space and pulling things out and installing them, under certain simple thematic groupings.

CBAs your first encounter and a way of cataloguing these works in your mind?

APTrying to understand the collection. We called it A Transition Essay. It wasn't a proper exhibition in terms of having a finalised checklist and so on. It changed almost every week. Some things had to be replaced because we realised they had to be restored. It was an interesting exercise for a team that was arriving at a new institution with a vast collection to approach it that way.

CBAnd also generous for the public.

API think so. There were many things that people had never seen. Masterpieces and works that had never been exhibited before.

CBAnything you found that had never been showed and that caught your attention?

APThere were several. But there was one particular pairing that we quite liked. Renoir's Pink and Blue (1881), possibly one of the most important in the collection, had just come back from a loan so we included it in the show and placed it next to an unknown artist, Liane Chamas' portrait of two girls from the 1970s. I came across many artists I had never heard about. When you are putting together an exhibition you are always a bit concerned about including artists that you do not know, but if the work is already in the museum, it has gone through some sort of criteria process that made me feel more at ease in terms of doing that. There was another grouping that united masterpieces and unknowns, Catholic and Candomblé iconographies: El Greco, Portinari, and Hirsch, an artist I had never heard about.

CBWhat did you learn in this process?

APA lot about many artists I did not know: Liane Chamas, Rafael Borges, Cassio M Boi. About the team and architecture, processes, restoration. But especially, many of these paintings in the collection became more familiar to me. That was very important. One thing that I have been quite interested in recently, which was already present in Mestizo Histories, an exhibition that I organised last year at the Tomie Ohtake Institute, is these artists that operate outside more orthodox modern and contemporary art circuits and market. These were quite important for the museum. I call them visionary, reclusive self-taught artists.

CBWho would be a good example?

APJosé Antonio da Silva. There have been quite perverse and paternalistic denominations for these types of artists and art, which we try not to use anymore. The first temporary exhibition that happens here in the museum is A Mão do Povo Brasileiro [The Hand of the Brazilian People], which already looks at this in 1969.

CBThis was when Lina requested people send objects to be considered by the curatorial team for the show?

APYes. It's coming from her experience in Bahia, from her Nordeste [Northeast] exhibition. And it's not by chance that when the museum opens on Avenida Paulista, this massive building that has this magnificent collection of European paintings, that this is the exhibition that somehow counterposes that.

CBIt was a huge statement.

APYes. And there's a certain roughness to the building—raw concrete, industrial rubber flooring, glass—and the programme that you see in this.

CBNowhere near as polished and idealised as a white cube.

APThis is interesting because when you think of the glass easels on the first floor, she is questioning the traditional exhibition models that are coming from these Beaux Arts museums because they are quite radical and they impose quite a lot of friction with a fine art European art collection such as this one.

CBBecause you see through the glass to other paintings and things can almost be superimposed visually?

APYes, they are glass and raw concrete. If you go to the Frick Collection that is the typical bourgeois setting you see these kinds of works in. Somehow, it's about being more democratic and open. My interest and Pietro Maria Bardi's as well, in these visionary self-taught reclusive artists, is also because to a large extent, modern and contemporary art is quite often produced or assimilated by the ruling class, the elite and these artists are coming from a different strata of society and they speak of different customs, cultures, and practices. So, for me, it's been really interesting to look at Maria Auxiliadora, an artist that we have a painting by. She died quite young in the 1970s, and she used to sell her work at Praça da República [a small park downtown] and she works with Candomblé references, capoeira and carnival—this is her iconography. She also has a very particular technique.

CBIs your looking at these artists and wanting to revisit the A Mão do Povo Brasileiro exhibition next year a way of somehow reclaiming a democratic feeling?

APHopefully that will be the first temporary exhibition with loans at the museum. It is not a reconstruction of the exhibition but we intend to revisit it somehow. As it was the first temporary exhibition at MASP then, it will be now. This year, we are only working with pieces from the MASP collection.

CBIn October you intend to re-introduce Lina's glass exhibition displays. What will the exhibition be?

APA selection of paintings from the collection. We have been thinking a lot about chronology. When the glass easels somehow withdraw the 'room after room' configuration, this also withdraws the traditional narrative of art history and offers a cacophonic display of a hundred paintings and the visitor can walk through and find his own narratives.

CBThere's no fixed route to navigate?

APNo, just this huge space and you can walk through whatever way you choose. We've been thinking about chronology and we don't know exactly what will happen, but there is this idea that the displays were in many ways—and this is Marcelo Ferraz's [an architect who worked with Bo Bardi] idea—that they were also a way of decolonising art history instruments.

At that time, we can see in photos, the works on the easels were organised in nucleuses: French Art, Brazilian Art... And we're thinking that maybe it's possible to advance on that and go further and question even more the formats that Western canonic art history offers us, doing this by organising things in a strict chronology. This does away with movements and generations and suddenly there are two things from the same year that are from different regions and don't relate to each other. We toyed with this a little bit in the exhibition Art in Brazil until 1900.

CBWhat other exhibitions are you planning for this year?

APOther than the ones we've spoken about, Art in Brazil in the 20th Century [opening Thursday April 9th] with about 100 works from the collection. What I realised through research—reading Zoiler de Lima [an architecture historian] on the relationship between MASP and Mam, Rockefellar and MoMa—when I came to the museum it was quite obvious to me that the museum was within the canonical Brazilian art history, and even European up until the 19th century. You see Bardi's [Pietro Maria Bardi was co-founder of the museum with Assis Chateaubriand] clear interest in figurative art, but a certain disregard for Geometric Abstraction.

CBWhich is strange given Brazil's art history.

APYes, but I feel he was a 19th-century man and she [Lina Bo Bardi who he was married to] was a very modern woman which you see in the building and her easels; there's a friction between the Beaux Arts collection and this very modern building. This friction, I think, reflects the friction between Lina and Pietro. But reading Zoiler de Lima, who did very interesting research into the Rockefeller papers and correspondences, he says that Rockefeller and MoMA, in the 1940s and 50s, were interested in disseminating Geometric Abstraction, internationally and also in Latin America and in Brazil, as opposed to Muralism (that was going on in Mexico).

Somehow, there was a certain understanding from MASP that Geometric Abstraction, in a very formal understanding, was quite a de-politicising artistic expression; it's much more difficult to engage politically and speak about politics if you are working with Geometric Abstraction—of course, later came Lygia Clark and Hélio Oiticica who would do this quite well.

This was the 1940s and 50s, a time of Constructivism, before all that. In the last 15 to 20 years, Geometric Abstraction has become the most important mid-twentieth century movement in Latin America, but if you look at Mari Carmen Ramírez, she writes a text, I believe in 1992, Beyond the Fantastic, that becomes a key text in which she says it's not just about the fantastic, Muralism, Frida Kahlo, and figurative painting, there are other things in Latin America—there's Geometric Abstraction. And she was, at that point, the only voice.

And now, 20 years later, it is the opposite, Geometric Abstraction is so dominant that we need to look back and reclaim the others. I tried to do this with Mestizo Histories—trying to look, even when at Geometric Abstraction, to do it through other paradigms and models. So for me, it's an interesting moment to look at [Candido] Portinari and [Lasar] Segall, Aldemir Martins, and Carybé.

CBEspecially for you, who built a career rooted in contemporary art. How is that process for you, beyond an education? Does it transform the way you now look at contemporary art?

APYes. But, I think there are a lot of histories and figures that need to be reconsidered. The last Portinari exhibition I saw was about eight years ago and it was so boring, there are many more interesting things to highlight in his work—he was part of the communist party in Brazil, for example.

CBSomehow, all of these artists fell out of fashion.

APYes, also, Di Cavalcanti, and there is so much interesting material about them. Aldemir Martins and Carybé, for example, if you look at the early works, from the 1940s and 50s, the figure of the Cangaceiro [northeastern countryside folk involved in uprisings and avenging their rights in Brazil] is very interesting.

What we have here, at the museum, is an interesting panorama of figurative art—Vicente do Rego Monteiro, Anita Malfatti, Segall, we have more than 15 Portinaris, a key Di Cavalcanti. But we noticed that there are three or four things missing, in terms of the canonical history of Brazilian art. We're missing Tarsila do Amaral—we only have a print—which is a major lacuna; we don't have Ismael Nery, Carybé, Djanira.

These last two don't appear in the academic canonical art history of Brazilian 20th-century art, but I think they are quite interesting. And looking at the Geometric Abstraction pieces we have here, a lot of them were gifted by the artist. But, of course, this collection was put together with a more aggressive impetus for the first ten years. Since this museum is known for its historic collection, we have also been thinking about how it can relate to the contemporary. Bardi had a relationship with artists in the 1960s, beyond these that I have mentioned, there are three key artists that the museum has works by: Wesley Duke Lee, Nelson Leirner, and we have Ar by Rubens Gerchman. When the museum opened again in 1969, there was an exhibition of Nelson Leriner's in the vão livre [underneath the canopy].

CBAnd that is another of the historic exhibitions that you would like to revisit in another exhibition next year?

API would like to, at some point in the future. But that space is not ours, it belongs to the City of São Paulo and once a week there is an antique market that happens there, so we are in conversation with the city in order to propose a cultural programme for that space and see if it is possible. It is not something we are going to impose. It is the community that will decide what is more important. The idea would be to have an exhibition programme with long-term installations.

CBThat space is also an important space for manifestations in São Paulo.

APThat is very close to the spirit of the space. John Cage came here at some point and said this was the architecture of freedom. So, it makes sense that these manifestations happen there, but it is also a space where different things can happen.

. . . contemporary art has to be understood in a much wider context.

CBWhat is the main curatorial challenge?

APThe collection is quite vast and we'd need different specialists in each field. At this stage we can't have that. So we have Adjunct Curators: Rosangela Rennó [the artist] for photography, the Adjunct Curator for Costumes and Fashion is Patrícia Carta [Harpers Bazaar Brasil], for Modern and Contemporary we have Julieta Gonzalez and we would also like to bring in one for European Art. But, when you start thinking, due to the dimension of the collection you'd need one person for each thing and that's not possible. So the Adjuncts come every so often to work on special projects, which is a good solution for us.

CBCan you foresee that in the near future there will be exhibitions curated by them?

APOnce a year they will curate an exhibition. This year, Patrícia Carta will work on the Rhodia Collection, which is one we already have. Next year, we are planning an exhibition around Brazilian Fashion from 1990s.

CBMASP has quite a large photography collection.

APYes, because of the Pirelli collection, more than 1,500 pieces. What we have just brought in is a 1930s collection in comodato [long-term loan with promise of gift] of 275 pieces from Foto Cineclub Bandeirantes. Fotoclubismo in that period was when different amateurs and professionals would meet and work together, organise exhibitions, and this was the most important one in São Paulo.

Many of the important mid-century figures, [Thomas] Farkas, Geraldo de Barros, and many others were part of this cineclub, which we will show this year. Julieta Gonzalez is kind of a Chief Curator-at-Large for me, and she is working on several different projects, including A Mão do Povo Brasileiro. Coming from just having organised Mestizo Histories, I realised that curatorially there are certain histories that need to be translated into exhibitions and tackled.

CBA couple of examples?

APHistory of Slavery, History of Colonisation, no one looks at this phenomenon in a more political way; History of Carnival, of Sexuality; History of Madness, because we have a fantastic collection of some 150 drawings that when we look up, come under a desenho dos alienados category [drawings by the alienated] which is not a very proper category, so we have to think this through and do more research.

CBAnything in terms of urbanism and city development?

APAnother exhibition we would like to revisit here, apart from A Mão do Povo Brasileiro, is one that happened in 1976, which will have its 40th anniversary next year, which is when we want to do it. GSP76 [Grande São Paulo 76]—I am trying to understand it. There was a lot of photography, it reported the crisis of the city and the growth in population and urbanisation challenges; it's very interesting and contentious. It shows São Paulo already as this megacity in 1976.

CBWe are all thinking about solutions for São Paulo now, so it's hugely relevant.

APExactly, and Rosangela is working on it with me.

CBAnything else that is important to state relating to your vision for the museum during your time here?

API'm coming from modern and contemporary art, mainly contemporary, and you can see from Mestizo Histories, that I feel at this time of my life, that contemporary art has to be understood in a much wider context. So for me, it feels right to be here in order to do that. —[O]