Benoît Piéron: Interview with the Vampire

In collaboration with Salzburger Kunstverein

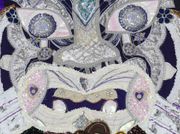

Portrait of the artist. © Benoît Piéron

Portrait of the artist. © Benoît Piéron

On a cold and rainy April afternoon in Paris, Benoît Piéron offered to meet for tea at his new studio after a visit to his candy-coloured solo exhibition Poudre de riz (Powder) at Galerie Sultana (2 March–20 April 2024).

Piéron was preparing for a performance, Absenteeism, to be presented at the Salzburger Kunstverein on 25 May as part of the exhibition The Myth of Normal. Chronical Contradictions (9 May–30 June 2024). The exhibition, curated by Mirela Baciak, explores the standards of 'normalcy' in health and societal expectations. Having spent March as a writer-in-residence at the institution and privy to the work being undertaken in the lead-up to the show, I was intrigued to interview Piéron, but first, I had to be invited.

As the artist reminded me, a vampire cannot enter a house without a formal invitation, a remark that sent a slight thrill up my spine. After Baciak, director at Salzburger Kunstverein, had done the honours, I stepped into what might have been a scene from Anne Rice's Interview with the Vampire (1976), a piece of literature that Piéron cites as influential.

I first encountered Piéron's work a year ago, when he participated in the group exhibition Exposed at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris.1 It departed from French art historian and critic Élisabeth Lebovici's powerful book What AIDS Did to Me: Art and Activism at the Close of the 20th Century (2017), which takes a searing look at the devastating epidemic and contemporary artistic production. One of Piéron's works for Exposed, titled Le Rayon (The Ray) (2023), streamed shifting light through the window and interstices of a hospital door relocated to the exhibition space. The work was rooted in the artist's specific memory of illness but one that resonated with the universal experience of childhood memories.

Later, at the Bourse de Commerce – Pinault Collection, I came across another work by the artist, this time presented alongside Félix González-Torres' photograph of the tomb of the modern lovers Alice Toklas and Gertrude Stein (Untitled (Alice B. Toklas' and Gertrude Stein's Grave, Paris, 1992).2 Piéron's work comprised a plush toy in the shape of a bat, made of repurposed hospital sheets, named Monique after the radical lesbian novelist and theorist Monique Wittig. Staring at the viewer, the unique critter brings a caring joy and soft materiality to mortality.

Like González-Torres, Piéron's artistry mingles the personal with the mythological. It crawls along the liminal medical and metaphysical boundaries between health and sickness, life and death, and presence and absence. Piéron was born with meningitis and spent much of his childhood in a hospital, where he narrowly avoided contracting HIV due to contaminated blood samples.

In our conversation, he discusses crip and queer references in relation to his recent projects, his appreciation for tales of vampires, the 'cute,' and American critic Susan Sontag, elaborating on how his artistic approach is rather philosophical, impacted by a lifelong experience with and alongside illness.

TBI would like to begin with Monique. Could you speak more about their psychopomp qualities and this sense of companionship in death?

BPMonique is part of my bestiary. It has been perched on top of the washing machines in the laundromat at Coming Soon, a group exhibition at Paris's Lafayette Anticipations.3 This is the prototype, which is not for sale, just like my juggling balls, the soft-to-touch shapes from my 'Art for Other People' series. I borrowed this expression from Richard Deacon, my teacher at the Beaux-Arts in Paris, who used it in reference to an economy of objects that are intended for a community and not for sale. Like Monique, juggling balls have a psychopomp role. I see them as existential guides that help one cross the Styx, the river of Night, quietly. I placed juggling balls in my grandmother's hands [in her hospital bed] so that she would have a presence to accompany her in death.

I have a long history of illness. I was born with meningitis, which left me hemiplegic. At the age of three, at the time of a contaminated blood scandal in France, I contracted leukaemia and was receiving treatment in one of the areas that received the bad blood. My paediatrician saw that many children were dying and suspected something, so he opted for intensive chemotherapy rather than a transplant, which would have meant a maximum number of blood transfusions. I had seven types of chemotherapy over three years. That protected me a little, but I was still transfused with the same batch of blood as the other children in the ward. In the end, two of the children were not infected with HIV. I was one of them. Afterwards, I was subjected to a series of tests to try and find out why I wasn't infected.

TBDid they find an explanation?

BPNo, they didn't. My body is a bit unusual. I'm not sure whether I bind viruses. I also have a neuromuscular disease with an endocrine component.

TBHave you met the other child who didn't contract HIV?

BPI haven't. That's the miracle of the hospital and its total social mix. There were some posh children in navy blue shorts and others who came from state group homes. Death picked one or the other. Afterwards, there would just be this pile of laundry in front of the door. We needed to give shape to this death hovering over us. In the haematology department, we were all fans of the comic book The Little Vampire. Our imaginary world enabled us to make sense of things where we couldn't find any. I used to think I was a Bavarian vampire and would sleep with my arms crossed over my chest. The idea of making a plush toy came later. The question is always what I do with my material: what's in my head, what's my past, like these hospital sheets, and so on. For Monique, I delved into the stuffed animals of DIY craft culture and, without realising it, I finally began to grapple with cuteness, a lead I've continued to develop since Poudre de riz at Galerie Sultana.

TBAre you familiar with critic Sianne Ngai's writings on the 'cute' as an aesthetic category?

BPThey were mentioned during a talk with Élisabeth Lebovici at the book launch of Slumber Party and Monstera Deliciosa (both 2024). The cynicism of these texts scares me a little. What interests me about the 'cute' is its interior, not the outer envelope, the device, or the wrapping paper. I truly like what's sweet and cute. That's where I come from. There's no cynicism in my work. I don't try to be extra clever, it's not a joke.

TBI want to show you this 'cute' work by Louise Bourgeois, Nature Study (Velvet Eyes) (1984), which reminded me of Cairn (2024), your monster made of sheets.

BPIt's so beautiful! It's perfect! I thought I'd seen the whole of her work when I wrote this text for the Louise Bourgeois anthology, but this one is new to me.4

TBDid you immerse yourself in Bourgeois' work specifically for that text, or have you always worked with her in mind?

BPI was moved when I visited her exhibition at the Centre Pompidou in 2008.5 In the text, I also refer to French music composer Elianne Radigue, Monique Wittig, and botany. I offer a fragmented vision of Bourgeois, inspired by Wittig's The Lesbian Body (1973), atmospheric and dreamlike. Bourgeois started making sculptures out of the milk boxes that the men of the family would empty every morning before leaving the house and slamming the door. It was her way of inhabiting the void created by their absence. And in a room of her own on the top floor of a New York building, she made do with what she could find, with what was available.

TBWhat would be your ideal studio?

BPIt would be a waiting room. I recently asked an artist at a talk what she would bring into a waiting room. She surprised me by returning the question. I'm interested in the waiting room itself, being in the void and the nothingness, in the loss of all hope and expectation, in the loss of reference points between beginning and end, in exploring the depth of time and finding a kind of immanence. For the exhibition Slumber Party at London's Chisenhale Gallery last year, I collaborated with Mousse Magazine to redirect the format of a waiting-room magazine to create an existential activity book.6

TBHow do you describe your way of working?

BPPlastic philosophy? I don't necessarily feel like 'being an artist.' I am more invested in creating moments, like the one we're having right now, which can take the form of a text. I also do a lot of workshops that bring people together.

TBLike this workshop at the Palais de Tokyo, during which you proposed 'cemetery honey'?

BPYes, I visited the Vienna cemetery in the middle of winter, and they make honey there. They place beehives near the tombs, and the bees gather pollen from the cut flowers and the flowers on the ground. In terms of decomposition and the transition from the animal kingdom to the plant one, from the dead to the living, the image is so beautiful. It's like a brunch version of Donna Haraway's theory. During a workshop for Exposed at the Palais de Tokyo, I suggested that each participant send a picture of a grave for a viewing session. We then softened the heavy atmosphere of this exchange by pouring cemetery honey into our tea.

TBWhich grave would you show a picture of?

BPI'd say the tomb of Gertrude Stein and Alice Toklas. I organised another workshop to study and collect the interstitial plant at Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris and I invited participants to meet at this tomb.

TBI only remember seeing that tomb covered in gravel, never in bloom as it appears in the photograph by Félix González-Torres.

BPI only recognised chickweed, a small winter purslane that can be eaten.

TBCan you tell me more about the snow globes you presented for the first time in Monstera Deliciosa at Mumok—Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien?

BPWhile organising this workshop at the Palais de Tokyo, I watched the film Tom et Lola (1990) at my hotel in Paris. (I've been living out of my suitcases until now. I only just signed my first lease at age 40.) The film tells the story of two children whose immune systems make contact with the outside world impossible, so they must live in protective bubbles. One day, they are given a picture album that makes them believe that happiness comes from outside. Tom makes a magnificent gesture. He cuts the album into small pieces and turns them into snowflakes. The outside world and the future are privileges that not everyone can enjoy.

Have you ever seen the Taj Mahal under pink snow? No. You can buy this kind of snow globe in the souvenir shop. So, for me, this project was about finding ways to enchant non-existent memories and set them in motion without ever travelling—which brings to mind Xavier de Maistre's cult book, A Journey Around My Room (1794). The snow globes also directly counter those charities that come to the bedside of sick children to make one of their wishes come true. There's a kind of competition in the ward to be 'the good patient,' in Susan Sontag's sense, the one who meets all society's projections, a desexualised or hyper eroticised body in some cases, yet distanced and confined to a singularity, an exacerbated romanticism. One doesn't need to agree with everything Sontag has said, written, or done, but she's a cornerstone of crip studies.

TBShe may be a bit classist, but she's one of a kind...

BPWhen you're ill, you must resign to the idea that happiness is on the outside. I have a photo of a neuromuscular re-education waiting room with a picture of an adventurer-type jungle landscape hanging in the mist. This is the opposite of Félix González-Torres' Untitled (Loverboy) (1989), which centres on the presence of absence and a very Foucauldian porosity... I prefer to bring things back to the banal, to re-enchant the banal. Enchanting or re-enchanting the banal, not transcending it. I hates transcendence. I prefer American feminist Starhawk's immanence, the light of interiority, which is also the light of illness.

TBDo you feel a certain 'privilege' because of your illness?

BPWhat do you mean by 'privilege'?

TBDo you think you might have developed a different perspective on life due to your near-death experience?

BPNo, because I'm also pretty down-to-earth, and it's shit to be prepped for permanent mourning ever since you were a kid. It's not what other people have gone through with the HIV-AIDS epidemic, but it's still quite a burden. A disabled life is a life with a lot of suffering, including physical suffering.

TB'Privileged' to have survived...?

BPI'd say it's more a question of survivor's guilt. But gradually, I'm letting go of that.

TBIs it because you've externalised your pathologies?

BPYes, I have made them public. While it doesn't exactly fall under artistic intent, I did testify on camera as part of the HIV/Aids, the epidemic is not over! exhibition at the Mucem in Marseille in 2021.7 I feel more damned than privileged. My last kidney cancer gave rise to a neurodegenerative disease, and I'm now losing my ability to walk. So, no, it's not a privilege.

TBForgive me if 'privilege' was the wrong word. I was transposing my own lived experience as I can sometimes feel privileged to have survived a long-term infection.

BPThat would be more connected to transcendence. It would be as if we should thank someone or something and feel we owe something.

TBI'm talking about the 'privilege' to navigate 'the kingdom of the well' with the citizenship from 'the kingdom of the sick' to use Sontag's terms. Living with HIV is now possible with medication. During the Covid epidemic, I remember feeling a slight sense of 'privilege' in the face of anti-vaxers, as my personal experience opened me up to knowledge, enabling me to overcome this binarity between illness and health. In your work, one can see the experience of illness encapsulated in a non-dramatic way, and I find it very empowering.

BPIn terms of not being stuck in a binary between life and death, I use the idea of damnation rather than privilege, but in the end, it's the same word. I'm more interested in the undead side of vampires and the thought of 'compost,' as adopted by Donna Haraway. I don't know how you felt about the Covid epidemic, between the onslaught of anti-vaxers and those who put their faith in medicine.

TBMedicine is the softest science there is.

BPI ask every doctor I meet whether they consider medicine a hard or soft science. If they say hard, I immediately stop working with them.

TBPharmacology, on the other hand, is quite a hard science!

BPYes, very much indeed. I'm a dreamer, I don't go any further than packaging, because I'm also a creature of the envelope, of drag...

TBDo you mean you're superficial? (laughter)

BPAbsolutely. I like to put rather heavy things in rather light packaging. It would be cool if we could link our medicines with the plants they come from, like with a label...

TBOr drawings to help us visualise the plants...

BPYes, we always imagine laboratories in Switzerland, but we don't imagine the power of the living. First and foremost, one should be grateful for the living.

TBWhat are your plans for the upcoming performance at the Salzburger Kunstverein?

BPI won't be traveling for health reasons. The piece will be called Absenteeism. I'll write a note of absence that Mirela Baciak will read. I'll have to feed my text, so if you ever have any references about absence to share...

TBLast year, together with the COYOTE collective, I took part in a project for the Thessaloniki Biennial, which we titled Absence is the highest form of presence, as some of us couldn't physically be there. It's taken from James Joyce's Ulysses.

BPI think I need to go to the library.

TBKnowing your references, you may find happiness in Proust...

BPI'm a plastic boy.

TBWho can we find in your pantheon? Derek Jarman? Have you ever been to Prospect Cottage?8

BPYes! We could find the Brazilian baroque sculptor Aleijadinho or the plush inventor Margarete Steiff. She's not really an artist, but she's a proto-crip. She made stuffed animals to commemorate dramatic events such as the sinking of the Titanic. She was giving shape to illness, turning what could have destroyed her into a strength. Catalan architect Antoni Gaudí's work should be reread and rewritten in the light of his disability. I also like the Czech photographer Josef Sudek, who was so afraid to leave his house that he finally transformed his studio from a garden shed into a darkroom and photographed the reality of his garden through condensation. And Albrecht Dürer, too! His Great Piece of Turf ! I'm always quoting his work, even in nail art...

TBWhat if you had to recommend a vampire book?

BPAnne Rice, of course. It's not one book, but a kilometre of books. And the novel Carmilla (1872) by Sheridan Le Fanu, in a beautiful red edition. Oh, and I'd also recommend the film Nadja (1994). The death scenes are filmed with a Fisher-Price camera. It's magnificent. —[O]

The Myth of Normal. Chronic Contradictions is on view at Salzburger Kunstverein until 30 June 2024.

1. Group exhibition, Exposed: What AIDS Did to Me, Palais de Tokyo, Paris (17 February–14 May 2023).

2. Group exhibition, Before the Storm, Bourse de Commerce – Pinault Collection, Paris (8 February–11 September 2023).

3. Group exhibition, Coming Soon, Lafayette Anticipations, Paris (28 February–12 May 2024).

4. Bernadac, Marie-Laure (ed.) Louise Bourgeois : Transatlantique. Paris: ER Publishing, 2022.

5. Louise Bourgeois, Louise Bourgeois, Centre Pompidou, Paris (3 March–2 June 2008).

6. Benoît Piéron, Slumber Party, Chisenhale Gallery, London (15 September–12 November 2023).

7. Group exhibition, HIV/Aids, the epidemic is not over, Mucem - Museum of Civilizations of Europe and the Mediterranean, Marseille (15 December 2021–2 May 2022).

8. Prospect Cottage in Dungeness, Kent, was purchased by English artist and filmmaker Derek Jarman in 1987, where he lived until his death in 1994.