Catherine Opie

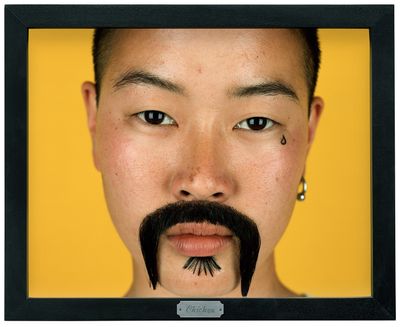

Catherine Opie. Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Lehmann Maupin, New York. Photo: Heather Rasmussen.

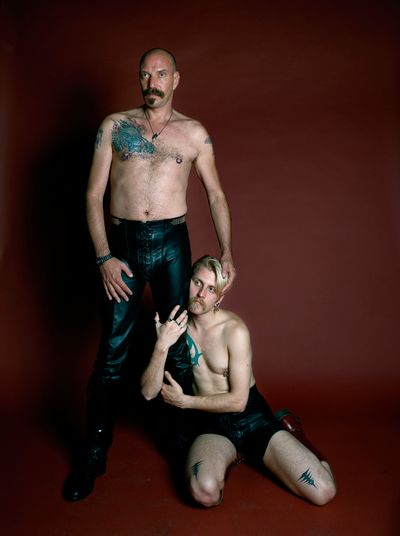

Catherine Opie. Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Lehmann Maupin, New York. Photo: Heather Rasmussen.

In the 1990s, American photographer Catherine Opie rose to fame for her portraits of the lesbian and gay community in Los Angeles. Inspired by the documentary photographs of Berenice Abbott, Lewis Hine, and Dorothea Lange, among others, Opie cast her otherwise misunderstood and marginalised subjects as dignified individuals through formal compositions and single colour backgrounds redolent of Hans Holbein paintings.

Opie's lesbian friends donned fake moustaches and beards to pose for headshots in 'Being and Having' (1991), her first ground-breaking work; while drag kings and members of lesbian BDSM and transgender communities were the models of her 'Portraits' series (1993–1997).

Opie further shocked America with images in which the artist appears topless and with her face hidden from view. She sits with her back to the camera in Self-Portrait/Cutting (1993), a stick figure drawing of a lesbian couple cut into her exposed skin as a rejection of traditional notions of domesticity. In Self-Portrait/Pervert (1994), created in response to the wider LGBTQ community's othering of the leather community to which Opie belonged, she wears a latex gimp mask over her head and the word 'pervert' is seen carved into her chest, the skin still red and swollen from the process.

Another consistent concern throughout Opie's practice has been with the contemporary American landscape, both physical and cultural. Her wide-reaching themes have included Los Angeles highways ('Freeways', 1994); Malibu surfers ('Surfers', 2003); high school football players ('High School Football', 2007–2009); and even the inauguration day of President Barack Obama on 20 January 2009 ('Inauguration', 2009). Between 2010 and 2011, she photographed Elizabeth Taylor's Bel Air residence, encapsulating the private and prized belongings of the late actress—who passed away during Opie's project—in intimate photographs.

Between 7 May and 7 July 2018, Opie exhibited photographs of California's Yosemite Park in her solo exhibition So long as they are wild at Lehmann Maupin in Hong Kong. Taking the genre of landscape, which has historically been marked with a sense of masculinity, Opie sought to introduce a feminine perspective to it by implying an experiential relationship between the human body and the wilderness in her photographs.

Blues and greens are seen blurred in Untitled #1 (Yosemite Valley) (2015) and Yosemite #2 (Yosemite Valley) (2015), while Cobalt Blue Sky (2015) captures Yosemite's famed granite cliffs and waterfalls against the stark blue atmosphere. The exhibition also showed ceramic tree stumps, Opie's first sculptures that echo the landscape in her works ('Untitled', 2011–2018).

Opie was born in Sandusky, Ohio, and settled in California after completing her studies at the San Francisco Art Institute (1985) and California Institute of the Arts (1988). An educator of 27 years, she has been teaching photography at the University of California Los Angeles since 2001. Between 26 September 2008 and 7 January 2009, a mid-career survey of her work—appropriately titled Catherine Opie: American Photographer—was organised by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York. Ever venturing beyond her comfort zone, Opie exhibited her first film The Modernist (2017) at Los Angeles' Regen Projects early this year (12 January–17 February 2018); it is scheduled to open at Lehmann Maupin in New York on 1 November, where it will be on view through 12 January 2019.

Our conversation took place at Lehmann Maupin Hong Kong, where Opie discussed her recent solo exhibition alongside Americanism, teaching, the future of photography and her first sculptures.

EAYour work has touched on many facets and symbols of Americana over the years. Today, the dangers of nationalism are becoming ever more apparent. How do you view Americanism today?

COIt's not a whole lot of fun to be an American right now. Earlier today [in Hong Kong], someone was asking me about my feelings about the American dream. They were surprised when I said that I'm questioning America's status as a democracy.

It's hard right now, and I'm not enjoying the country that I'm living in. But it's my country, so I'm not going anywhere. I'm very politically involved, making sure that people are voting, and giving money to the right causes. I'm also fairly protected because I live in California, and California is viewed as the 'Left Coast'. But all the nationalistic rhetoric is still incredibly upsetting.

Personally, where I've noticed it most is when exceptional people apply to the programme I teach at UCLA. I had one woman who was from Haiti, who had DACA status, and another student from Mexico who couldn't get scholarships or funding because of their immigration status. There has been a profound sense of loss in relation to the larger diversity of students that are being brought into the programme. It's important to have diversity, and my work has always encompassed that.

EAYou've mentioned that you've touched on so many themes and subjects throughout your career because you have questions that you're trying to answer. What are these questions?

COAll kinds of questions. It relates to the way that we either begin to look at people, ideas of community, our relationship to both things that we see, and necessarily don't see; about the spaces in between. I'd say that my questions have a lot to do with ideas of democracy and humanity, and trying to create work that allows a pause for the ability to meditate on those thoughts. I'm interested at this point in taking a more meditative than reactive approach, and I think maybe that's just my 57-year-old self, versus my angry 29-year-old self.

EAWhat do you think photography's democratic potential is?

COIt evokes within people the ability to place themselves within whatever they're looking at. We talk about democracy in terms of social media, which totally has changed the way that people interact with photography. But photography can be used to question systems, or ideas around representation. I'm always pushing that, both through portraiture and landscape. I'm pushing it through real, basic tropes within heavily aestheticised images. There is a certain beauty within my work and I'm perfectly happy to allow that to draw the viewer in.

EAWhen taking a portrait, how do you hold your subject? And how do you hold the viewer in an image—are the two related?

COI hold the audience's gaze by getting them to think about the actual history of art. The 'High School Football' series refers to the history of painting to a certain extent; it's using a certain aestheticised language. You're seduced into this moment, but then it's utterly contemporary. At the same time, you must consider the vulnerability of these young men, which isn't what people necessarily think about in relation to high school football players.

EAWhat do you tell your subjects when you are taking their photo?

COI tell them where to look. I tell them how to hold their hands. I tell them how to hold themselves. In Daddy Irwin and Mark (1994), for example, I wanted Mark to wrap himself around Daddy Irwin. There is a certain classicism that draws you into the work. You're not necessarily thinking about the queerness within the photograph, you're thinking about the actual people, the pose, and the position. They allow you to consider the person rather than their piercings, because of what the eyes are doing.

EAYou've said that your butch photos from the 1990s were read as very radical at the time, but maybe not so much anymore. Do you think there is a way to make radical images today?

COI don't know, I think that the 'Self-Portrait' series were radical for people back then, and they still are. Me wearing a moustache might have been considered radical in the 90s, but I don't think it still is.

I think that people often think that making work that's transgressive is radical. I'm not interested in transgression in the sense of an intense representation of sexuality. I have done it in the past because of what I'm representing within the community, but I'm never interested in shocking viewers. It was always surprising that people found the 'Self-Portrait' series shocking, because that wasn't what I was asking; I wasn't trying to be transgressive, I was just trying to use the photographic language.

EAYou often apply inside jokes about photography in your works.

COYeah, like the lens flare in the works in the exhibition So long as they are wild. The midnight blue colour in Cobalt Blue Sky (2015) is made by just racking the aperture down. It's a technique that was used when shooting western movies and they didn't have the proper light, so they just made the aperture smaller. People can't tell whether it's night-time or twilight. There's an incredible simplicity to the making of this body of work, but its utterly embedded within the language of photography.

EAThis humour is also present in your portraiture.

COYes. When I took Anish Kapoor's portrait (Anish, 2017), I cut off his toe. Anish is so formal as an artist; I love his work, and I love him as a person. And I love that suddenly making him unbalanced by cropping the toe out was antithetical to how he is as an artist. It's also antithetical to how I am as an artist. In the photograph David (2017), in which David Hockney sits so perfectly in the chair, you can see the scuff marks of his studio on his shoes.

I needed to have these moments where I was also pushing myself to do something that would normally drive me crazy.

EAIs it important for you to feel uncomfortable?

COYeah, I think sometimes.

EAHas playfulness or wit always been important to your way of thinking?

COIt's funny, I have a much bigger sense of humour than my work has ever conveyed. I've had so many different people say to me, 'Oh my god, I was so scared to meet you'. I always wonder why. When I talk, or when I teach, my students are constantly laughing at me, and I look at myself as a little bit goofy. But my work has never conveyed that.

EAI think it does. Perhaps it's just hard to see or dig it out of it.

COI think it does in 'Being and Having'. I think 'Being and Having' is a hilarious body of work, with these women with fake moustaches.

EAThey seem very aware of their own comicality. You can see the netting below the false moustaches.

COExactly. I'm working in a very different way. The little jokes are there—perhaps you must be a certain kind of photographer to recognise them. I don't think that they're readily available to a general audience.

EAThe experience of growing up in small-town America necessitates a sense of jest, or else you can't get through it.

COGrowing up in Sandusky, Ohio, you need a good sense of humour.

EAWhat is the most important thing that you can teach or ask of your students?

COTo have perseverance as an artist. I teach them how to be critical, but not too critical. Students say: 'Well this was done, and this was done, and how can I ever make anything that's new?' And I reply, 'Nobody ever makes anything that's new, you only have a conversation within the history of art within our own questions we're trying to answer.' I try to foster an intense criticality within their practices, but not so intense as to end up in a highly intellectualised space where they shut down their creative process. It's a very interesting balance in that way, especially in terms of academia.

EAEarlier at the gallery, someone mentioned that your work exists in a world that's hyper-saturated with images and speculated the end of fine art photography. You responded by saying that you don't like broad declarations like 'the death of painting'. I assume that means you don't foresee the death of photography either?

CONo, I don't believe in the death of anything. I understand from a critical place why that language is adopted. It's similar to when Craig Owens suddenly decided that there was post-feminism. And I was like, 'Oh, so now it's just "post"?' I think critics feel a need to make these declarations while people are just going along and trying make what they want to make.

EACrisis sells magazines.

COPeople have certainly said that over the years. It's been said and then it's been repeated. I think everything transforms. I've gone from film to digital myself. Even though I don't digitally manipulate my images, I still use the camera as if it were a film camera. That alone changed my practice because I take way too many photographs now, and it's much harder to edit. Before, I could only afford ten sheets of film per person, and then that's what I shot. But now it's easy to overcompensate.

EAWhere do you see the future of photography going?

COOh, it'll change so much. Phones are getting so good. I also think that there was an enormous movement against observational photography in recent decades; I think that photography became very staged, and street photography was lost. I think that will change—people are beginning to look back at the seventies and eighties in photography in the same way that they're doing in fashion. Even looking at some of the ads here in Hong Kong, where there are big billboards like LA, I'm noticing that the imagery is moving away from the idea of staged photographs.

EAHistorically, large monumental things—national parks included—have long carried masculine connotations. Given the vaginal connotations of the waterfall photographs in So long as they are wild, and that the abstracted photos subvert the normative ways of seeing, do you consider these images a way of queering the landscape?

COIt's interesting, people have been asking that. It's not quite queering the landscape, but rather about creating a certain kind of femininity within it. We usually think about the Western landscape through the male lens. So, I think of it rather as creating a different type of intimacy and a relationship to it; that's a cognitive relationship that's more connected to the idea of the sublime. I'm trying to create these existential moments within the idea of landscape, versus the heroic or iconic landscape, such as Yosemite.

EADo you have any special relationship with Yosemite?

COI was commissioned by the General Services Administration to do a piece that bisects six floors of the federal courthouse in Los Angeles, and I chose Yosemite's falls as the subject. While I was in Yosemite photographing that piece, I decided to just make my own work. I had already been doing abstract photographs of national parks. From that, I decided to make a book based on Yosemite, and then from that I created this series. I didn't necessarily go out with the intention to take on Ansel Adams. It was more that the courthouse commission turned into a separate project.

EAIn addition to photographs, the exhibition at Lehmann Maupin included tree stumps made from ceramics. You mentioned that working with clay was similar to the darkroom process.

COYeah, I hope that I'll imagine other things besides stumps, but right now I'm just super happy making them. I don't feel the same kind of pressure as I do with my photographic practice. I think it's nice for an artist to remember that they can do something that they love, even if there is the possibility of failure. If there's a lot of passion, it means something. I think artists forget that. They're often looking at the criticality of their own critic within their head, and as a result they deny themselves a certain amount of pleasure or passion. One day I made a stump, and then I just kept making more stumps, and instead of being embarrassed by it, I just decided to embrace the stump.

EAIt's important not just for an artist, but for everyone to have something that's more enjoyable and less pressurising than their main work. When discussing the same concept a couple years ago, Sean Scully told me that Daniel Day-Lewis makes shoes.

COThat's cool. I mean, I can imagine Daniel Day-Lewis making shoes.

EAWhat are you working on next?

COI'll show The Modernist at Lehmann Maupin in New York. The film is comprised of over 800 images that create this kind of beautiful sequence, but it's about the failure of utopia. The character is making this large collage, and starts burning down the modernist houses. I was thinking a lot about the history of political collaging, especially in relation to where we are right now as a country, and what it means to be a political artist, or not be a political artist. What do we have at stake in that? I just spend every day cutting out magazine and newspaper images and archiving them in boxes. I want to make a stop motion animation of the creation of collage. We only usually ever see the collage put together, but what does it mean out of all these images that create meaning? It could be another failure. —[O]