Chitra Ganesh on Utopia, Futurity, and Dissent

Chitra Ganesh. Courtesy Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art. Photo: © Kristine Eudey, 2020.

Chitra Ganesh. Courtesy Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art. Photo: © Kristine Eudey, 2020.

Working across comics, drawings, paintings, installations, murals, texts, and films, Chitra Ganesh grounds her practice in feminist studies, science fiction, queer politics, popular culture, and social histories.

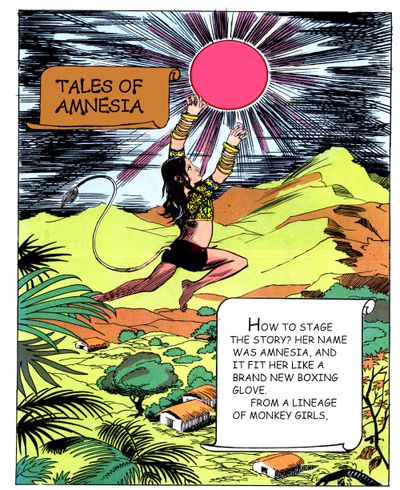

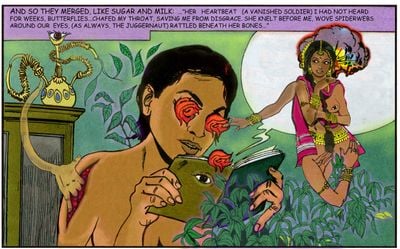

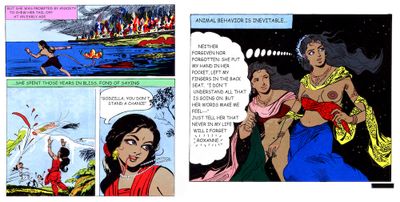

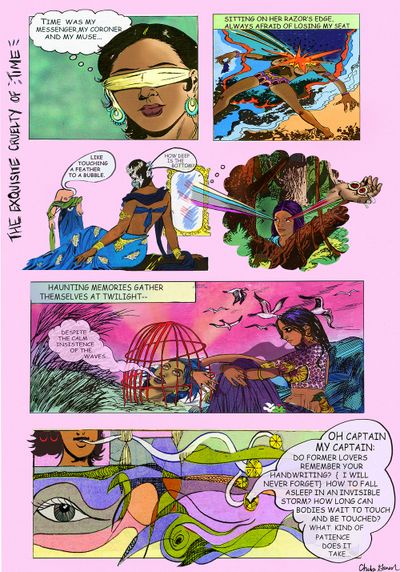

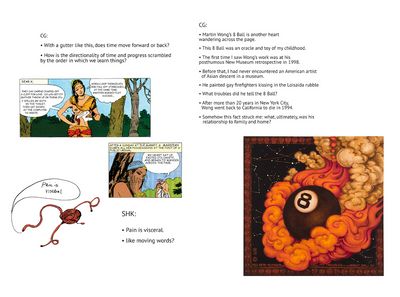

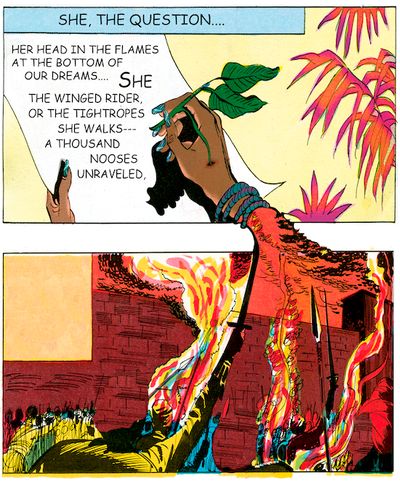

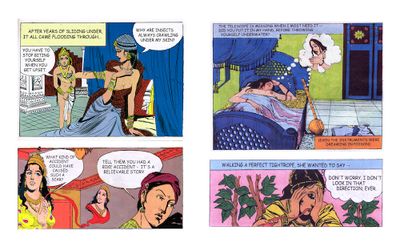

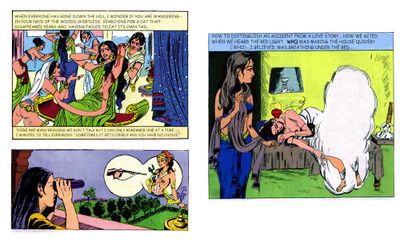

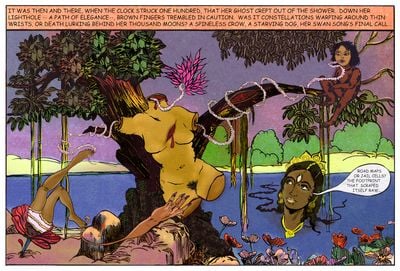

The 24-page comic book and installation Tales of Amnesia (2002–2007), for instance, references the Indian comic book series, Amar Chitra Katha, upending the heroic male saviour narrative by presenting alternative explorations of sexualities and critiques of power.

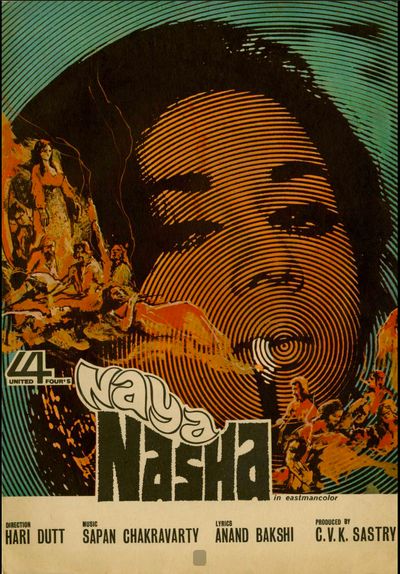

In the work, Ganesh also turns a critical eye to the iconography of Hindu goddesses as well as the visual language of Bollywood movies from the 1970s and 80s, exploring gestural language and aesthetics of a time when some of the cultural representation of gendered identities were less conservative and experimental compared to the present-day right-wing populism in India, and globally.

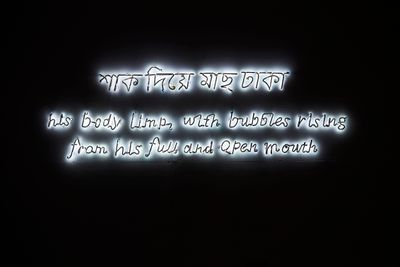

Between 2018 and 2019, Ganesh presented multi-venue exhibitions in New York City, which travelled to South Asia. Her garden, a mirror at The Kitchen (14 September–20 October 2018), for example, took as its point of departure Bengali author and social reformer Begum Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain's feminist science fiction novella from 1905, Sultana's Dream, to reimagine collective and individual roles in times of crisis. Ganesh presented a project based on the novella at Dhaka Art Summit 2020 (Seismic Movements, 7–15 February 2020), which involved 27 linocuts imagining a world led by women innovators.

Scorpion Gesture at the Rubin Museum of Art (2 February 2018–7 January 2019), presented in collaboration with animation company the STUDIO NYC, saw Ganesh present five animated interventions drawing on the iconography of artworks relating to Indian Buddhist mystic Padmasambhava and Maitreya, known as the Future Buddha, sited within the museum's pre-modern collection galleries, later shown at Times Square in New York City (1–30 November 2018) and at the Kochi-Muziris Biennale (12 December 2018–29 March 2019).

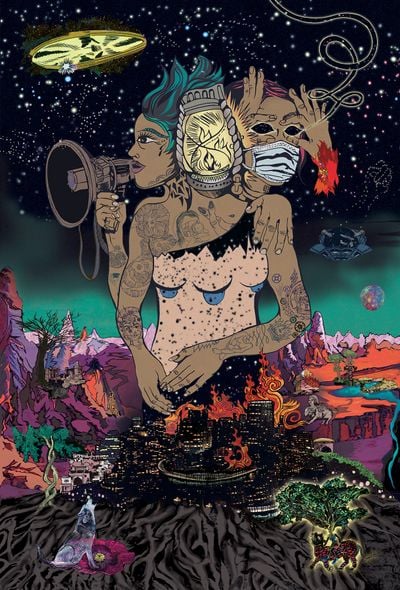

Launched on 18 October 2020 and running for one year, Ganesh's largest installation to date, A city will share her secrets if you know how to ask (2020), takes over ten window panels on the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art's façade in New York City's SoHo for its annual QUEERPOWER public art commission.

Ganesh's commission engages with New York City's past, present, and future in representations of long erased architectural histories from 19th-century Black settlements including Seneca Village in Manhattan, Little Africa in South Carolina, and 17th-century Lenape settlements in present-day New Jersey, Delaware, southern New York, and eastern Pennsylvania; to more recent events in the U.S.A. of violence and murder directed at trans and gender nonconforming individuals, as well as gentrification and displacement of queer and immigrant communities.

This conversation between Ganesh in Brooklyn and Jareh Das in Warri, Nigeria, unfolded via Google Meet and several emails. The discussion reflects on unexpected Bollywood connections across South-South geographies, collaboration as an anchor for peer and intergenerational exchanges of ideas, the importance of popular culture as an entry point to overlooked histories, and the rupturing of colonial legacies by the diaspora.

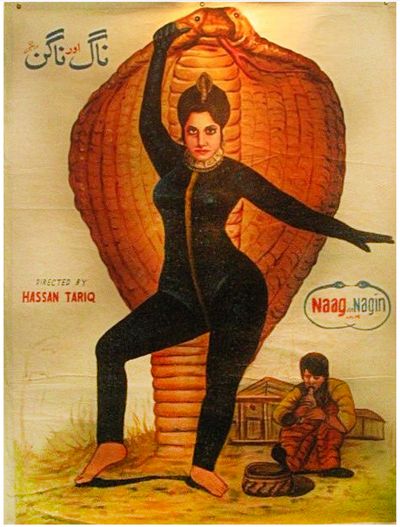

JDI grew up in Lagos in the 1990s where everyone watched a lot of Bollywood movies and it is still very popular. I remember Nagin (1976) centred on a female protagonist who could transform herself into a snake, and the movie follows her quest to avenge the death of her lover. I bring this up because I recall, in these movies, prominent themes of the 'avenging woman' who was also often depicted as a goddess.

What themes and elements of the visual language of Bollywood movies interest you, and when did you first engage with these movies and the visual and popular culture around them?

CGIt's amazing that you bring up Nagin! One of the posters for this film, in particular, has been iconic for me. Growing up in the Queens and Brooklyn boroughs of 1980s New York City—before the birth of VCRs and home movie culture—there was a local theatre that screened Bollywood films, so I actually saw the film on screen.

For many immigrants, especially those from middle or lower-middle-class backgrounds like my family, popular culture in the form of music, movies, and comics were cherished by my folks and their peers and provided a bridge of sorts to the idea of home.

These wonderful South-South connections, including the immense popularity of Bollywood in Nigeria, is a reminder of a conundrum: how do genres and forms like Bollywood, with ubiquitous global influence in shaping affective response, aesthetics, and desire, remain relatively overlooked and consistently marginal in the United States?

At that time specifically, the global embrace of South Asian popular film running across the former Soviet Union through Afghanistan, Iran, Morocco, Kenya, Nigeria, and more was pretty much non-existent in America. I began to consider these omissions in my practice, and explore the sensual excess in the costumes, posters, and performed femininity that characterised 1970s and 80s Bollywood film.

I found equally compelling visual affinities with the wider history of print culture that the film posters evoked, revealing how melodrama, excess, and the collision of opposing realities took shape in the painted poster form, integrating typography, colour printing, and graphic design.

Visual languages in Bollywood's orbit became conduits for expressing an expanded sense of the real, heightening the fantastical and symbolic via a hybrid use of graphics and paint. Their unique visual language continues to inform aesthetic and archival impulses of a generation of artists spanning from painting to experimental film. They have certainly informed my own practice and language, including A city will share her secrets if you know how to ask, a large-scale public installation for the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art's QUEERPOWER commission.

JDThis also brings attention to the disappearance of print culture and the move to the digital, and how movie posters have now become reproductions of reproductions, especially here in Nigeria with regards to advertising Bollywood movies.

CGYes, these affinities with prior modes of print culture are both geopolitically and generationally determined. Mine align with late 1970s to 80s Bollywood, and with comic books of that period from both Asian and American comics.

Visual languages in Bollywood's orbit became conduits for expressing an expanded sense of the real, heightening the fantastical and symbolic viaa hybrid use of graphics and paint.

In the last several years, Bollywood itself has become more nuanced and wide-ranging in terms of expanding narratives offered around sexuality, class, and caste. These changes are also geopolitically informed and reflect local political struggles and contestations, such as the shift from filming in Kashmir to Europe, and a recent focus on stories set in smaller cities and towns—decisions whose implications are being understood over time.

JDThinking about unexpected connections across geographies facilitated by popular culture, have there been instances of unexpected connections as your works travel globally to different contexts?

CGHaving the opportunity to exhibit my work globally has been very meaningful, especially as it allowed my work to circulate and gain recognition outside of the United States well before it was legible here.

This was especially true with the comic works such as Tales of Amnesia, Architects of the Future - Away from the Watcher (2014), and The Exquisite Cruelty of Time (2010), as they gained visibility due in part to the fact that the medium of comics is accessible, and translates seamlessly to digital. That body of work ended up tapping into a collectively held memory bank for audiences in India and its diaspora that had read that comic series as children. That's hundreds of millions of people for whom the form immediately evokes potent signifiers and memories.

Showing in the U.K. has also allowed my work to be accessed through the lens of centuries of shared history and colonial relations with South Asia. There is a greater sense of legibility and historical connection to the layered visual histories and cultural narratives that inhabit my work.

This context is quite different in the United States, where the histories of people of Asian descent continue to be produced as marginal to American history, in regard to both the vital contributions of and brutal acts against people of Asian descent in this country.

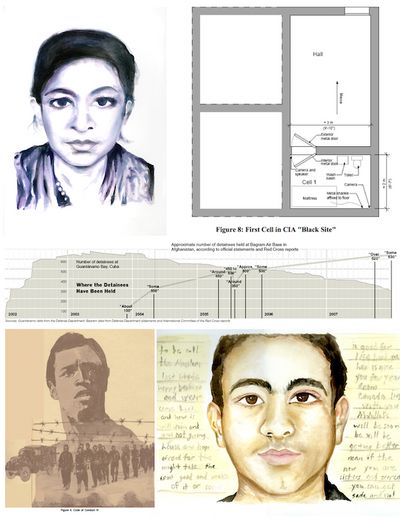

The idea of shadow narratives that shape experience but are excluded from mainstream political discourse has been a foundational aspect of my practice. It gained new urgency in proximity to American history since 11 September 2001, when there was a widespread disappearance, deportation, and indefinite detention targeting predominantly South Asian and Muslim communities.

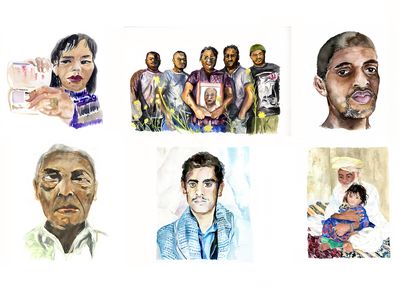

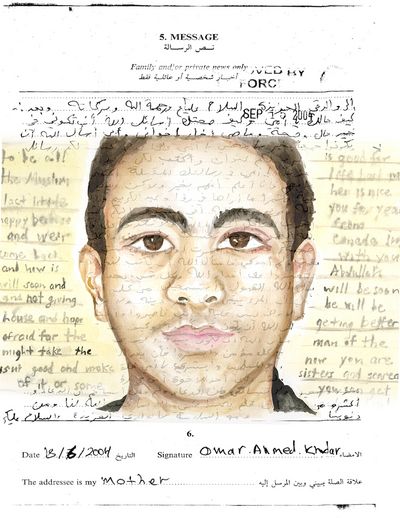

I learned of these instances of longstanding erasure and violence while developing Index of the Disappeared (2004–ongoing), a long-term collaboration with artist Mariam Ghani, which is both a physical archive and a mobile platform for public dialogue that foregrounds the difficult histories of the immigrant 'Other', and dissenting communities in the U.S. since 9/11, as well as the effects of U.S. military and intelligence interventions around the world.

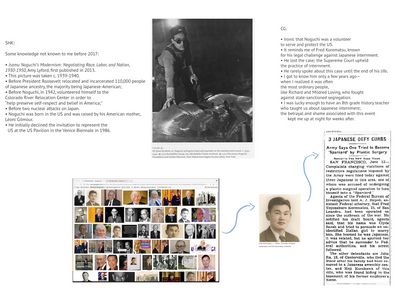

Index of the Disappeared is an archive that can be installed as a reading room in a gallery or community space. We connected the dots between current processes of indefinite detention and previous moments in American history, including the history of Japanese internment in the 1930s United States.

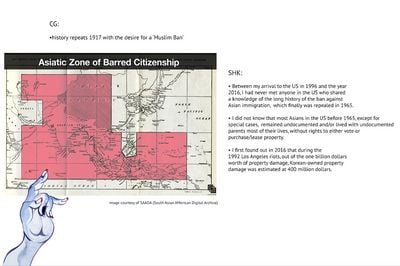

These connections emerged once again in sharper detail in 2016, as I researched and protested the Trump so-called Administration's 'Muslim ban'. This attempted ban repeats history, and ironically was introduced almost 100 years to the day after another immigration ban, which happened in 1917.

This idea of shadow narratives that shape experience but are excluded from mainstream political discourse, has been a foundational aspect of mypractice.

The research that grounds my practice helped me understand the long history of racial exclusions in the U.S., also reflected in Asians being barred entry into the U.S. between 1917 to 1965 with few exceptions.

This is when something finally clicked for me—why, growing up, I rarely met another person from the subcontinent who had an American accent, whowas not marked as a foreigner or threat in relation to mainstream American society.

I realised the huge vacuum of Asian cultural production I experienced growing up was a result of xenophobic migration policies, obscured by the idea that Asians didn't contribute to building this country or just started arriving in the U.S.A. a few decades ago. This manifests differently in Europe, because there was much more visibility around the anti-colonial struggle and having some kind of a legacy of being a Commonwealth subject.

My introduction to cultural studies, through the work of Stuart Hall, for example, coincided with a moment when Blackness was being mobilised in Britain differently than it is today, as Black Britain including South Asians offered a different lens through which I saw the connections forged by the legacies of colonialism in varied geographies.

Showing my work in Asia, there are formal and conceptual nuances that people have a keen awareness of, seeing the signifiers and visual languages in my work as vital references that are still alive and well in their contemporary lives that offer entry points, such as traditions of mural-making, calligraphy, comics, and mythic stories.

This is a welcome departure from the otherness of Orientalist discourses that have historically shaped Euro-American interpretive frameworks of art from beyond the West.

JDCollaboration is prominent in your practice. I'm thinking particularly of the project 'Between You and Me' with Sung Hwan Kim and the ways you both reference texts and visuals to explore settler colonialism narratives of disappearance and erasure.

CGEach collaboration unfolds as it progresses. My project with Sung Hwan Kim transpired organically, building on close to 20 years of friendship, an ongoing discussion of feeling illegible in America, and of the anti-Asian sentiment that runs like a thread through one's life in the West, including one's professional worlds.

Our process of exchange was a natural outgrowth of a casual practice of reading and exchange via messaging one another on WhatsApp. At the time, Sung Hwan had just completed a project for the 57th Venice Biennale in 2017, and had begun to research early Korean immigration to the U.S.A., specifically the West Coast.

I was completing a research fellowship at the South Asian American Digital Archive and reading a book called Bengali Harlem and the Lost Histories of South Asian America (2013) by scholar and filmmaker Vivek Bald who charts the historical migration of Bengali people from South Asia to Harlem in the 1920s. There was a sizeable community in Harlem and in around New Orleans, where Muslims settled, with some of the men marrying Black women and forming communities that were generally African American and Bangladeshi.

We were both in the process of learning what these early patterns of migration were outside of what we would never be taught in school or college at the time, but they're actually being excavated now.

Growing up, I knew about Yuba City, which is a small town in California, which has a fourth-generation Punjabi-Mexican population where the majority are descendants of Sikh migrant labourers and the women that they married are Mexican.

Sung Hwan and I were thinking about these questions and these moments that might reveal like another kind of narrative that you don't get to see. I also really like to collaborate because I get to think with people I love.

JDIt's interesting what you highlight: how collaboration might be seen as an overlap of thought processes and crossovers between lines of thinking.

CGYes, or even seeing it as a practice of a closer reading with someone else and integrating practices. My collaborative work with Mariam Ghani, Index of the Disappeared, which we started in 2004, centred around the Republican National Convention that year. As a response to the election, we were interested in having a conversation about what was overlooked in the larger electoral discourse.

We were thinking about mass deportations, men of Muslim and South Asian descent being targeted, along with men from Russia, China, and Sub-Saharan Africa—all part of the so-called 'axis of evil' post-9/11. This was how we came together to do this particular project and because this was on my mind at that time.

JDI'm also curious about how you approach intergenerational collaborations, and how this contributes to mobilising communities of support?

CGI led a course at Rhode Island School of Design teaching Drawing, Narrative and Materiality in Contemporary South Asian Art, a programme funded by patrons of the school who were interested in integrating contemporary South Asian art into Rhode Island School of Design's broader contemporary art curriculum back in 2014.

It's crucial to share in varied perspectives, particularly given the art world is extremely unregulated and opaque, making the anecdotal exchange of information all the more valuable.

I'm still in touch with the majority of students from this seminar and a few have become good friends, so teaching in itself forges intergenerational links. I have been actively involved with the Queer Art Mentorship programme, the Skowhegan School residency, and have been in touch with tutors and mentors I met close to 20 years ago, including Coco Fusco, Martha Rosler, and Zarina, which I greatly appreciate.

It's crucial to share in varied perspectives, particularly given the art world is extremely unregulated and opaque, making the anecdotal exchange of information all the more valuable. For example, conversations around structural misogyny and racism initiated by a previous generation of artists continue to be contested and have barely entered the field. And nobody's going to teach you what to look for in a contract or how to approach an opportunity in grad school.

Open conversations, cultivated by shared values and trust, are extremely supportive ways to gather information and make informed decisions.

JDDo you use fragmentation of the body as a political tool for re-imaging a future free from an obsession with 'perfect' wholesome bodily categorisations, which would allow for multiplicity and fluidity?

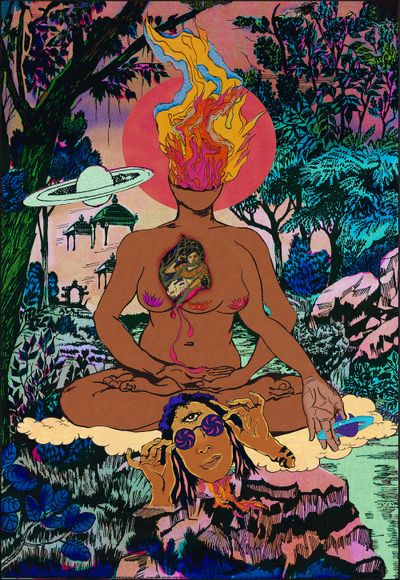

CGThe move to represent multiple iterations of the body and femininity has always been important to my work. In the mythic narratives that inform some of my figurations, there's almost always a portion of the story that loops around how the body came to be what it is, and the inextricable relation between creation and destruction.

This is evident in stories such as that of Coatlicue in Aztec mythology, whose body torn asunder gave birth to the moon and stars, or the dismemberment of Sati's body into 51 parts that formed sacred sites across Indian known as the Shakti Peeta or refigured feminist literature such as Toni Morrison's Beloved (1987) or Mahasweta Devi's Breast Stories (1997), and even speculative queer tales such as Marlon James' Black Leopard, Red Wolf (2019).

I am interested in how some of these have implications for the cerebral, shifting gender, and thinking about expanding what we have come to know as the normative body. This isn't about the body being a site of harm or liability; rather, such narratives offer different propositions for bodily configurations and how bodies can exist, often paradoxically embedded in misogynist stories.

Here's a larger psychic process at play that manifests in the figural—one of deconstructing histories and ideas, moving beyond how we learned them in school, to putting them back together again to understand them in a new light. This is something that happens in my work.

JDHow has your engagement with Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art over the years informed this new QUEERPOWER window commission? I am also curious about the history of stained-glass windows and the window itself serving as an apt metaphor and vehicle for passages of time in SoHo?

CGI've been familiar with the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art's institutional commitment to queer artists; for incipient projects by younger queer folks, curators, and established but consistently under-recognised queer artists, programming that I have both participated in and greatly benefitted from.

To your thoughts on how the passage of time in relation to SoHo exemplifies a city that is historically and presently in constant transformation has been on my mind for a while, and especially so after how the Covid-19 pandemic initially affected New York City.

Growing up in New York City meant that I saw art in public spaces, from graffiti, light installations, painted movie posters, chalk drawings, and other makeshift interventions well before I began visiting museums, so the idea of public space as a lifelong urban citizen is something very important to me.

The QUEERPOWER window commission reflects this liminality that many citizens of New York City live in and with...

We're in a really interesting moment with the pandemic that has created a shift in the neighbourhood and city in general. You have all of these wealthy people fleeing the city, and major things like Broadway, live music events, and movie theatres are all shuttered, meaning that there's going to be such a radical shift towards outdoor gatherings.

Gentrification and the displacement of queer and immigrant communities is something that has been happening in New York City and around the world. As in the rest of the world, the pandemic sheds a harsh light on existing economic, racial, and structural disparities—what was already ripping at the seams is now completely unravelling and/or dismembered.

The QUEERPOWER window commission reflects this liminality that many citizens of New York City live in and with—and the imagery is connected to a visual language I'm using to think about utopia, futurity, collective knowledge sharing, and mobilising dissent. This includes racism and state-sanctioned violence against Black people, which is just as much a pandemic if not more than Covid-19, which laid bare the disparity between how communities are affected.

In New York City, you can see this across neighbourhoods like Manhattan where the people with antibodies represent 19 percent of the population, while in Queens, that figure was as high as 50 percent. Then also the fact that over 30 transgender people have been murdered in the U.S. so far this year, and you can imagine how many deaths have not been reported. The majority of those murdered have been Black trans women.

I am also thinking about protests related to queerness and how bodies come together in challenging discrimination, rejoicing in queer life, and how bodies have to convene under vastly different circumstances and constraints differently in the next few years.

JDBegum Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain's Sultana's Dream (1905) is mind-blowing, as it speaks so much to the present in terms of re-imaging society without an oppressive and dominant patriarch, and more meaningful human-nature relations.

I was also struck by an exchange when the protagonist Sultana tells Sister Sara, 'Your Calcutta could become a nicer garden than this if only your countrymen wanted to make it so', to which Sister Sara responds: 'They would think it useless to give so much attention to horticulture, while they have so many other things to do.'

How do you relate to the environmental theme central to the text?

CGThe humour and inversion in Sultana's Dream is interesting, and used to expand upon themes of collective care, education, and protecting the environment.

When I did this Sultana's Dream project in Bangladesh for Dhaka Art Summit 2020, which included site-specific architectural installations, this brought up some ideas around materiality, fabricating in a different climate, and environmental conditions, which led me to think about biodegradable materials and how to build in this way.

Ideas around vernacular architecture and tropical modernism that I was researching for the work really blew my mind. This also stood in stark contrast to how the current U.S. government's move to undo every kind of environmental protection further obscured the chaos of the pandemic and racial strife. Everything from rolling back coal and methane pollution regulations, making it easier to frack and drill, government revisions of sea levels that indicate flood zone dangers, and gross negligence of communities affected by the sharp increase in fires, floods, hurricanes, and toxic water.

In this way, there are a lot of ideas in the story that resonate with the present moment—including the crucial role of education, believing in science, of welcoming and aiding refugees, and towards radical gardening, water storage, and solar power.

JDWhen did you first read Sultana's Dream and how have metanarratives served as a tool for the QUEERPOWER commission?

CGI had been introduced to the story initially by an auntie, but there is a whole genre of Bengali science fiction. The second time it came up was in 2007, at a collaborative exhibition with the same name of the South Asian Women's Creative Collective called Sultana's Dream curated by Jaishri Abichandani (4 August–1 September 2007).

When I began to think with Sultana's Dream to make a body of works, I dug much deeper into the story, and its place within a larger body of literature, specifically the Bengali and feminist science fiction.

During that period, I was also reading Ursula K. Le Guin, Octavia E. Butler, and Manjula Padmanabhan, alongside feminist and science fiction texts by writers such as Ismat Chughtai and Jagdish Chandra Bose, and reflecting on the connections between fantasy and speculation rooted in non-Western and non-white contexts.

One of the first books I read that brought me back to thinking about Sultana's Dream was Ben Okri's The Famished Road (1991), and more recently Marlon James's Black Leopard, Red Wolf (2019), and N.K. Jemisin's The City We Became (2020).

JDWhat emancipatory and resistance discourses or strategies have you returned to or revisited as a way to make sense of the present and posit a more optimistic future? I'm thinking here about micro acts that may or can have macro political consequences.

CGThat's an amazing question. One of the things that is important to think about the future is one outside of this genealogy of progress of forever moving in a positive direction away from technology, barbarism, and so on.

The future and the past are not consecutive points on a straight line, they are much more dynamically and dialectically involved. One metastrategy would be to dislodge the many myths that structure our understanding of history and progress and have been harnessed in the service of justifying brutality.

The past must be properly understood, accepted, and seen with open eyes in order for a just future to materialise. This is a long-term process and we are just at the beginning.

For example, calling out the complete falsehoods we were taught in school related to American history, that North America was sparsely populated by a physically vulnerable Indian population before colonial subjugation, producing and framing the European conquest and subsequent genocide as nearly 'inevitable'. That confederate histories are 'under attack'.

Or that the ideologies being perpetrated by India's current right-wing government that India has always been a Hindu land, and thus is 'a country for Hindus'. That caste has always been central to the religion, both paving the way for atrocious anti-Muslim violence and the ongoing lynching and sexual violence faced by Dalit and Adivasi communities, most recently in the global attention on the gang rape of a Dalit girl by four upper-caste men in Hathras, Uttar Pradesh.

Both myths are being perpetuated by moves that hope to scrub diversity and oppression from school textbooks, in both India and the United States. These conversations are happening in the face of a rising global right-wing authoritarianism, all over the world. So reading and being able to discern and question the true value of what you are reading is another micro act that has a macro consequence.

Micro acts include seeing the world with one's eyes fully open, however painful that may be, and holding complex and contradictory realities within the same frame.

Other evidence of the politics and promise of assimilation is afoot in the rising viability of queerness' compatibility with mainstream goals and institutions where a focus on successful queer icons, gay marriage, and more, highlight narratives of progress and success only available to a few, that can be used to deflect attention from the vast economic gulf leading to severe crises of mental health, homelessness, murder, and injustice experienced daily by poor queers and queers of colour worldwide.

It's about asking the right questions of history and power, of whether something needs to be completely torn down in order for it to function properly.

Do institutions need to be rebuilt from the ground to truly repair and rebuild the existing structures? How can our work become a refuge for these possibilities?

I'm incorporating certain gestures, certain kinds of bodies, citations from queer politics and art, figures from the past and present, and bringing that into a shared frame, a roadmap for understanding the present and future, to really be able to disassemble and reassemble things in a newly meaningful way.—[O]