Dhaka Art Summit 2020: Seismic Movements

Clarissa Tossin, A Queda do Céu (The Falling Sky) (2019). Laminated archival inkjet prints and wood. Exhibition view: Seismic Movements, Dhaka Art Summit, Shipakala Art Academy (7–15 February 2020). Commissioned and produced by Samdani Art Foundation for DAS 2020. Courtesy the artist, Commonwealth and Council, and Samdani Art Foundation. Photo: Randhir Singh.

Seismic Movements, the fifth edition of the Dhaka Art Summit (DAS 2020) (7–15 February 2020), plotted movements, solidarities, and exchanges across the Global South through the work of over 500 cross-disciplinary artists, scholars, curators, and thinkers including Otobong Nkanga, Elizabeth Povinelli, and Salah Hassan. Organised under the artistic directorship of Diana Campbell Betancourt, DAS 2020, the most ambitious edition of the Summit to date, wanted 'to think of new forms of togetherness' and 'write (art) history from new perspectives'. To a great extent, the Summit succeeded in its aims.

Spread across four floors of the Shilpakala Art Academy, DAS 2020—which continues to feverishly reject the biennial tag—comprised a series of nine chapters and seven sub-chapters each interacting with one another, furthered by two symposiums and a moving-image programme, with auxiliary talks taking place throughout the Summit's duration.

Following the curatorial logic suggested by the title, the nine chapters were organised into various kinds of 'movements': Geological Movements, Colonial Movements, Independence Movements, Social Movements and Feminist Futures, Collective Movements, Spatial Movements, Moving Image, Modern Movements, along with the Samani Art Award. The exhibition design—devised in collaboration with Srijan-Abartan, a cross-cultural and cross-disciplinary research project aimed at creating new tools and methodologies for more socially, culturally, and environmental sustainable exhibition displays and strategies—responded to this multiplicity of activity by creating fuzzy non-boundaries between sections, fuelling what felt like a purposeful confusion.1

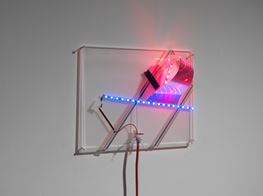

While successfully managing the tightrope of random and choreographed discovery in most places, some precision was lost in On Muzharul Islam: Surfacing Intention, co-curated by Campbell Betancourt with Sean Anderson and Nurur Khan to showcase works responding to the legacy of Muzharul Islam, Bangladesh's most prominent Modernist architect, who had a crucial role in the country's nation-building process. Here, Haroon Mirza's blue-lit installation A Lesson in Theology (2019–2020), re-imagines Islam's 'frequencies of thought' through sound and light; while Hajra Waheed's looped video The Spiral (2019), which gives the impression of moving beneath a forest canopy at night, considers the spiral as reflexive and interdependent structure, echoing the dizzying logic of DAS 2020.

The first floor of the Shilpakala Art Academy comprised a large portion of the Collective Movements section, which featured projects, archives, and artworks by over 40 collectives from across the world. Standing tall in the centre was the site-specific installation Reclamation (2019–2020) by artist Taloi Havini, made in collaboration with the artist's matrilineal Hakö clan members of the northernmost part of the Autonomous Region of Bougainville, Papua New Guinea. The assemblage, made with natural materials that were harvested by the artist and her clan, referenced Hakö structures of ritual and exchange. Reclamation was used as a gathering place and site of some of DAS 2020's live programming, involving grassroots organisations from the region, animating its form every day and holding the attention of much of the visiting public.

Not easily missed nearby was Geographies of the Imagination, an ongoing research and exhibition project initiated by SAVVY Contemporary in Berlin, which aims to un-map prevailing geographies of power. This iteration of the project, based on interviews with researchers and scholars across disciplines in Bangladesh including Sadya Mizan, Yasmin Jahan Nupur, Shayer Gofur, and Nazrul Islam, was visualised as an incomplete timeline that takes two parallel points of departure. The first was the 1905 Partition of Bengal, and the second was the 1884 Congo Conference in Berlin, where 15 colonial powers decided on the division of African land for their exploitative gain. To visualise this information, the Dhaka-based collective Jothashilpa worked closely with cinema banner painter Ustad Mohammad Shoaib to create the final murals for the project.

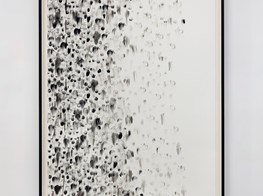

Within the Summit's visual maze was a quiet mini-exhibition curated by Mustafa Zaman, Nobody Told Me There Would be Days Like These, which mapped the history of Bangladeshi groups who fostered art, theatre, film, and literary movements in the 1980s. Nearby, as part of the thematic section Geological Movements, Karan Shrestha's three-channel video installation in these folds (2019), was accompanied by a large ink drawing illustrating the precarity of everyday life in Nepal. The central video assembles found-footage covering natural disasters, political instability, revolutionary upheaval, and state-sponsored violence in Nepal, while two other videos shot in documentary style reflect on the place that transcendental practices have in coping with everyday violences, like the ritual sacrifice of a pig and the repeated action of Tibetan Buddhists performing chhakk ('prostrations').

Nearby and winding up three floors was Korakrit Arunanondchai and Alex Gvojic's collaborative sculpture of a naga (a semi-divine being that can assume both human and serpentine form), which transformed into a stage for the artists' performative work, Together. Commissioned by DAS 2020, the performance created an environment based on Ghost Cinema, a post-Vietnam War phenomenon in Thailand where audiences attempted to connect with spirits through outdoor screenings, made popular by American soldiers. Powerful choreography, amplified by heavy use of laser and lighting, reflected on the intertwining of indigenous practices of ritual and technology, and the role that colonial violence and presence plays in it.

As a whole, DAS 2020 felt like a multi-limbed organism that sought sustenance through process, dialogue, learning, and exchange over passive engagements with slickly installed objects.

The Otolith Group's 'Rituals for Temporal Deprogramming: Video, Film and Talks Programme' which ran through the course of the Summit to confront 'the violence of images and the threat of sounds' and 'intervene in the foreclosures of colonial time and racial space.' This was one of DAS 2020's highlights, not only for the mindful curation of screening cycles that included works by Hadeel Assali, Taysir Batniji, Ana Pi, Rania Stephan, Rehana Zaman, among others; but also for the incredible conversations with invited artists and theorists (often via Skype) that followed, with speakers such as Tony Cokes discussing the formation of subjectivities through race and gender; and a discussion between art historian Elizabeth Giorgis and historian Sanjukta Sunderason on the politics of famine against the backdrop of oppressive regimes in South Asia and North Africa.

Another discursive contribution was 'Condition Report 4: Stepping out of line; Art Collectives and Translocal Parallelism', the fourth edition of RAW Material Company's biannual symposium programme, which focused on art collectives and trans-local parallelisms, delving into practices and forms of production that have informed various kinds of collectivisations through history and in the present. Beginning each day with a different performance or screening, the symposium was divided between specific lines of enquiry. The final day asked: 'what happens after the seismic movement?' and opened with Extinction Surgery, a performance by Roydeb Roaja and the Hill Group considering what happens after a flock of birds disbands, which was followed by the panel discussion, 'The death of the collective' between Kemang Wa Lehulere, Merv Espina, Emeka Okereke, and Dhali Al Mamoon, moderated by Cosmin Costinas.

Dire times call for apocalyptic vocabularies, says Nilima Sheikh, whose new work on Kashmir, Beyond Loss (2019–2020), takes the form of narrative scrolls that reflect on practices of mourning, signalling the valour of the women of Kashmir in the face of an oppressive world outside. The work was shown near two pulp prints by Somnath Hore from his 'Wounds' series of the 1970s—torn and punctured planes of white paper—followed by two sketches by Zainul Abedin, widely considered the father of modern art in Bangladesh, and a teacher to a young Somnath Hore in pre-partition Bengal. Both of Abedin's sketches are about the Bengal famine, which has been attributed to policies implemented by Winston Churchill during World War II, and are powerful in their depictions of the pain and violence of this trauma.

These works led to a three-channel black and white video installation by Thao Nguyen Phan, titled Mute Grain (2019). Commissioned by Sharjah Art Foundation for Sharjah Biennial 14 (7 March–10 June 2019), the work examines the 1945 famine in French Indochina during the Japanese occupation (1940–1945), in which between one and two million people died of starvation, poetically weaving together oral histories, folk tales, and lyrical chronicles to tell a story that history left behind in Vietnam. This moving blend of reality and fantasy is not exhausting despite the trauma it touches on—rather, it leaves space for quiet and affective contemplation of the complexities of such legacies that linger in the present.

In the section Colonial Movements, where themes of indentured labour and the machismo of nation-building were explored, one work similarly stood out as a solemn memorial not only to a brute history, but to resilience against all odds. Adebunmi Gbadebo's 'True Blue' series of silk screen prints on sheets constructed with beaten cotton linters and human hair collected from black barbershops, were hung across a wide wall: each sheet recalling documentations of genetic histories based on the archives of plantation owners, with the indigo-tinged hair dye referencing the history of slavery within Gbadebo's maternal family history.

While there weren't many misses in DAS 2020, it would be remiss if I didn't mention New Mutants (2017–2020) by artist Adrián Villar Rojas, 400-million-year-old fossils of extinct undersea creatures embedded into the floor at the Shilpakala Art Academy entrance: a disappointment in its failure to activate in the same manner as other installations at the Summit due to its positioning as a thoroughfare. Also disappointing was the installation of otherwise commendable video works by Jonathas De Andrade (the animated film Pacífico, 2010), and Liu Chuang (the three-channel film, Bitcoin Mining and Field Recordings of Ethnic Minorities, 2018) and Himali Singh Soin (a two-channel video, we are opposite like that, 2017–2019). While Andrade's work suffered because of no seating and too much light, Chuang's and Soin's works had poor sound, low resolution projectors, and strange spatial placements.

By contrast, the Samdani Art Award exhibition, which showcased commissioned artworks of 12 emerging Bangladeshi artists under the mentorship of curator Philippe Pirotte, was beautifully installed with great precision. Among the stand-out contributions was Soma Surovi Jannat's spatial intervention, Into the Yarn, Out in the One (2019–2020), which takes the form of thin poles elevating a white spiral structure, upon which drawings of imaginary beings, from plants to creatures, are placed.

As a whole, DAS 2020 felt like a multi-limbed organism that sought sustenance through process, dialogue, learning, and exchange over passive engagements with slickly installed objects. It managed to maintain a fine balance in foregrounding Bangladeshi artist practices and (art) histories by contextualising them in a 'contemporary' that did not feel tokenistic or patronising, while engaging with a dynamic global milieu of approaches and practices.

There is a joke that floats about in South Asian art circles on how we need to be invited to Europe for an event to be able to meet each other, not only for the fact that there are hardly any institutions that can afford to fly people down to this region, but more grimly because people still seem to prioritise Western institutional presence over local and regional engagements. While the West's big museums and galleries were not absent from DAS 2020, the Summit brought a constellation of practices, artists, and collectives that are rarely seen, let alone heard, together. —[O]

—