Dr Dieter Buchhart on Basquiat

Dr Dieter Buchhart. Photo: Mathias Kessler.

Dr Dieter Buchhart. Photo: Mathias Kessler.

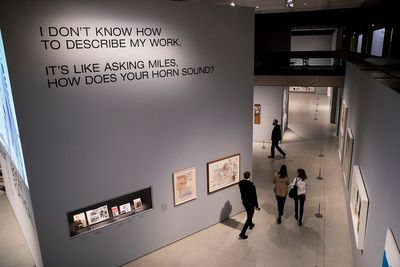

Curator and scholar Dr Dieter Buchhart is the co-curator of the Barbican's current exhibition, Basquiat: Boom for Real (21 September 2017–28 January 2018), alongside Barbican curator Eleanor Nairne.

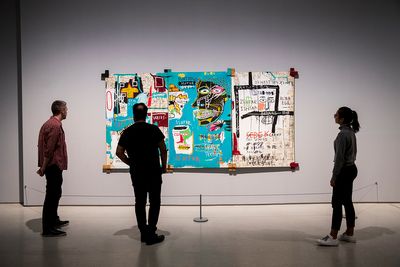

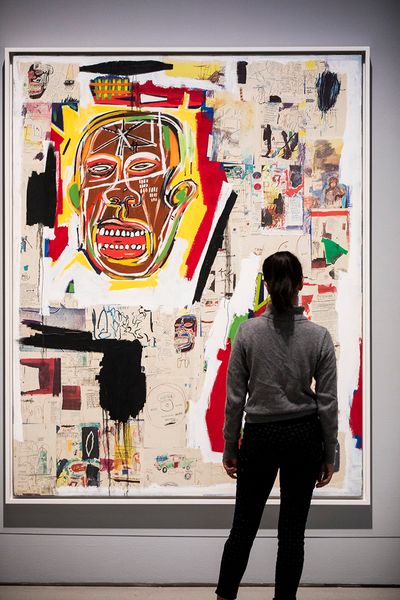

Organised in collaboration with the Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt and with the support of the Basquiat Exhibition Circle and the Basquiat family, the exhibition brings together more than 100 works from international museums and private collections, and represents the first major institutional exhibition of Jean-Michel Basquiat's work since the artist's 1984 show at Edinburgh's Fruitmarket Gallery. (Though the Serpentine did stage a small exhibition of major paintings from 1981 to 1988 between 6 March and 21 April 1996—described as 'the first solo showing ... in a public gallery in Britain since his death.')

Boom for Real offers an impressive overview of the life and work of an artist Buchhart has described as conceptual, above all—an identification that manifests in the sheer explosion of creativity that unfolds over two floors of the Barbican Art Gallery where this exhibition is staged.

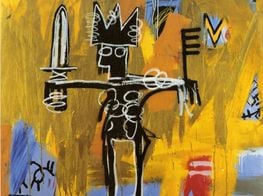

Aside from an excellent selection of paintings—including Leonardo da Vinci's Greatest Hits (1982) and a self-portrait from 1984—and a series of images that document the artist's days as street artist duo SAMO© (along with school mate Al Diaz), there's a room dedicated to New York / New Wave, a group show Basquiat participated in at PS1 in February 1981, curated by Diego Cortez; and another in which Downtown 81 (1980–81/2000), in which Basquiat plays a young struggling artist in the City, is screened on a loop. In one section, the record featuring rappers Rammellzee and K-Rob that Basquiat not only produced but designed the cover for, Beat Bop (1983), is shown alongside the painting Hollywood Africans (1983), which shows the artist with his musical collaborators situated inside a composition that calls out the inherent racism in Hollywood culture.

Taken cumulatively, Boom for Real achieves a remarkable feat, offering a linear, chronological way through which to enter into Basquiat's practice, while expanding on that line through the many different paths that his work as an artist took him down. One highlight is a room dedicated to pages from the artist's notebooks; a section that seems to condense another exhibition Buchhart, a Basquiat specialist, curated at the Brooklyn Museum with Tricia Laughlin Bloom, former Associate Curator of Exhibitions, Brooklyn Museum—Basquiat: The Unknown Notebooks (3 April–23 August 2015).

Buchhart has curated a number of notable Basquiat shows. Namely, the 2010 retrospective at Fondation Beyeler in Basel, Switzerland, the year that would have been the artist's 50th birthday (9 May–5 September 2010), and the Art Gallery of Ontario's exhibition, Jean-Michel Basquiat: Now's the Time (7 February–10 May 2015), which was organised in collaboration with the Guggenheim Bilbao (the exhibition was staged there from 3 July to 1 November 2015).

The latter exhibition was touted as the first thematically—rather than chronologically—organised exhibition of Basquiat's work. Most recently, Buchhart opened an exhibition he curated for Almine Rech Gallery in New York, Words Without Thoughts Never to Heaven Go (31 October–16 December 2017), which explores 'the word as an image and its metonymic relation to the motif itself', and which sees Basquiat presented among the works of Juan Gris, Barbara Kruger, Pablo Picasso and Martin Kippenberger, among others.

In this conversation, Buchhart, who first encountered Basquiat while pursuing a PhD on Edvard Munch, talks about Basquiat's relationship to art history, and how he views the market influence and impact on the artist's legacy. As the Barbican exhibition press release states, no works by Basquiat exist in British museum collections, with museums in the United States faring little better.

(According to one 2015 essay by Bob Nickas published in ARTnews, 'Only the Whitney Museum and the Museum of Contemporary Art in L.A. are able to present a fully formed view of this artist, with significant paintings among a half dozen of his works in each collection.') Through this discussion, Buchhart also talks about curating the Barbican show and how it expands on his prior research and curatorial projects, offering his thoughts on the recent USD 110.5 million sale of an untitled 1982 painting of a head by the artist at Sotheby's New York in May 2017, making it the most expensive artwork sold by an American artist at auction, and the sixth most expensive artwork sold at auction.

SBI wanted to start with how you discovered Basquiat through Edvard Munch, whom you were researching for your PhD. You have talked about the resonances between the life and work of Munch in the 1880s and that of Basquiat in the 1980s.

DBWhat fascinated me is the similar energy that these two artists share, even if they lived a century apart. The timing is very important, here, though, because Munch developed in a different way after the 1880s, but during that decade he was so radical. He was attacking the canvas and the layers of colour in a way no artist had done before. I saw and see this energy in the works of Basquiat.

What's very interesting when you look at both artists is that they are still relevant today. I always try to work with artists who I feel that, even though they might not be alive, still have something to say now, are relatable to us, and from whom we could learn something or get something out of their work. I think this is true for both Munch and Basquiat.

SBMoving on from Munch, you curated Poetics of the Gesture: Schiele, Twombly, Basquiat at Nahmad Contemporary in New York in 2014. Twombly aside, I'm curious about the connections you found between Basquiat and Schiele, because in these two figures you almost have a mirror image.

Both were two young artists, completely radical, who existed outside of the status quo and who both died untimely deaths at around 27/28 years old, leaving behind an incredible body of work that explores the body as a site of sheer and total expression. How did you view the relationship between these two?

DBBetween Schiele, Twombly, Basquiat, it's the line. It's an inimitable line that they create, which gives the line power. The line defines the body as the demarcation between the inner and the outer. The pressures from the outside world kind of squeeze the rendering of the body in both cases. Both of them—Basquiat and Schiele—also had great respect for older artists when they were young and working: in Schiele's case it was Klimt and in Basquiat's it was Warhol.

SBThinking about Schiele's bodies, there was this angst that demanded to be expressed, which is present, as you say, in Basquiat's lines.

DBThis is also something that Munch expressed very well, and Basquiat expressed it, too, especially when it came to everyday racism. There is also this idea of reclaiming history, which is something else that connects these artists.

I would say that when I began looking at these artists together, it started off more with an intuitive connection; of course, looking at the line, and as you mention the biographies of Schiele and Basquiat, for instance. With Munch, it's this way of disrespecting what was there in art history before, while also respecting this history, at the same time.

SBBasquiat was so aware of art history and its canon, and he worked with and against it in order to work himself into it.

DBHe was interested in everything surrounding him, not just for picking up knowledge, but as an artist. As you mentioned, he was very aware of art history. He was a regular visitor of MoMA when he was very young, and knew the collection there better than most people. He later started collecting so-called outsider artists like Sam Doyle. Arne Glimcher told me that Basquiat was always coming to his gallery every week and asking him if he had anything new from Jean Dubuffet.

But what did he see in museums' collections? The great masters. What he didn't see in the museums was images by African-American artists, or of African-American, Haitian, or Puerto Rican people. He didn't see that, so that's what he painted and drew. Of course, he was not the first artist to do this, but he was the first artist who had this breakthrough to become a star.

SBThis also had to do with the market in America at that time, which played such a huge role in shaping Basquiat's life as an art world star who wanted to have a career, as any artist does, but who also had to battle prejudices and institutional racism. History was against him, almost, but the market supported him.

DBHe had history well against him, but he reclaimed history.

SBAnd it seems the battle continues in death. There was the recent auction price of his work, when an untitled 1982 painting of a head sold at Sotheby's New York for USD 110.5 million, making this the most expensive artwork sold by an American artist at auction. Yet, famously there is still a lack of Basquiat's work in museum collections; Mary Boone was really emphatic about the fact that US museums refused works that were offered to them when he was alive.

DBYes, Herb and Lenore Schorr, who were great supporters of the show here in London, have told me several times that they went with a masterpiece by Basquiat to MoMA and they didn't want to take it. And of course it led to frustration with some dealers and collectors, because of course you couldn't really understand why his art would not be accepted.

SBThis brings us back to the fact that the majority of Basquiat's work exists in private hands or collections.

DBYes, but you know, don't forget one thing: time. Basquiat would have been 56 years old today; a mid-career artist. How many mid-career artists have many works in museums? Never forget that he was so young when he was working, and then of course you also have the issue of racism that he faced during his lifetime, and after. Some institutions did not even accept work when it was offered to them, but some dealers had big collections of his art, which ultimately went to other private collectors. I think we just haven't gotten to the moment yet where many of his works are in museum collections. But it will happen.

SBSome say the prices of his work just became too high for museums to acquire.

DBWhen collectors entrust their collection to the next generation: that will be the way works get into museum collections. There are some rather good collections in museums like the Whitney Museum of American Art and also the Centre Pompidou, which has one great work. There's the Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam, and the Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst in Aachen with true masterpieces. So there were a few museums buying his work at the time; actually most of them bought his work during his lifetime.

SBThat's interesting, because it means that there was more institutional interest in Basquiat's work in Europe than in America during his lifetime.

DBYes, for sure.

SBAnd this added to Basquiat's frustration, right?

DBFrustration, yes, about the everyday racism, but not about his recognition as he became an art star also in the US during his lifetime.

SBThis recognition, though, largely came from the market, which built his career in life, and continues to develop it in death. The people who have his work—the collectors, the dealers—are part of this support system that has been maintaining Basquiat's legacy. But there still appears to be some aversion to his work when it comes to recognising its critical importance.

DBI often get asked the same question about that 2017 auction: 'What's the reason for this price?' My answer is that his art is really that superb and art historically important. Actually, there's kind of a hidden racism to say, 'Is he that good?' I mean, nobody would question Cézanne.

Basquiat's trajectory always had to do with the market, but in my understanding, the reason he became such a success is because he was so talented. It's his combination of words and drawing and colours; his own visual language that he created. The words he uses are often like concrete poetry, and when you read them aloud, they feel like a sound poem, which creates a kind of parallel structure in the work. Through this, you feel secure when seeing the images he created—but then you are interrupted by those symbols he adds to the construction of the picture: a guitar, real feathers, a word, whatever.

SBThis recalls what you mentioned about the line being such a crucial element to reading Basquiat's work. Actually, the contemporary Chinese ink painter, Wang Huangsheng, talks about the line as the point from which everything begins; it's where language comes from.

DBTrue, every word starts with a line. And every word you write is a line. But with Basquiat it is about the inimitable line, a unique line you only find in very few other artists in art history: Schiele, Picasso or Twombly.

SBThinking about this line, you've curated a number of Basquiat exhibitions. There was the 2010 retrospective at Fondation Beyeler in Basel, Switzerland, and Jean-Michel Basquiat: Now's the Time (7 February–10 May 2015), which was organised by the Art Gallery of Ontario's exhibition in collaboration with the Guggenheim Bilbao (the exhibition was staged there from 3 July to 1 November 2015). The latter show was touted as the first thematic exhibition of Basquiat's work, as opposed to the chronological approach normally taken to the artist's work.

How does the Barbican show fit into this?

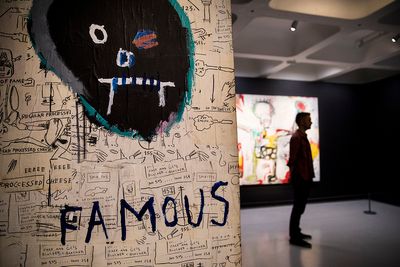

DBWhat you will find in the Barbican exhibition is a focus on the inter-disciplinary approach of the times and of Basquiat himself. You will find him as an actor, a musician, a poet, a painter, and a writer—writing was very important for him. In the end, his works are drawings—collages and drawings—and this is very important to understand with his work, which brings us back to the line as the element that carries throughout in his work.

The Barbican show is the first time an exhibition is asking these questions; like, what does performance mean in Basquiat's work? Where and how was he embedded in the New York scene? What did that mean? Where's the connection between his poetic conceptual graffiti at the beginning of his career, and the paintings he would create later on? Where does the fact that he actually played himself as an artist in the film Downtown 81 come in because this all goes together? 'Boom for Real' is a phrase he used pretty often, not so much in his work, but more as a description of an artistic strategy. It's a little bit like an explosion, and every part, every bit of information of it becomes equal. That's what happens in Basquiat's art—he equalises everything. But on the other hand, by bringing very different themes together, he creates new spaces for our thinking.

This show totally differs from those I've done before, because it shows more the man behind the work, too. With the Beyeler and Paris shows, it was about making a big splash about showing this artist who has done amazing work, had an amazing career, and was huge even in his lifetime. But it was very much about reconfirming his position, too; to give the people the chance to dive into his practice.

There was also the show at the Art Gallery of Ontario, Now's the Time, also shown at the Guggenheim Bilbao, where for the first time his work was grouped into themes. It was about reclaiming history, representing the duality in his works, the question of racism: everything that had not been focused on. Then there was the notebook show at the Brooklyn Museum, which added to the picture that Basquiat had a clear relation to concrete poetry and created his own poetry, but in the same style that we see in his other works. Now we have this Barbican exhibition, which combines his music, his readings and his acting altogether, and it's all interconnected in the space of the Barbican.

SBAnd in the centre of that exhibition you have the large projection of him in his studio. Given your long relationship with Basquiat both as an art historian and as a curator, how have you come to know Basquiat the man, since you must have an intimate relationship not only with his work, but also with who he was?

DBThis is what the sisters of Basquiat, Lisane and Jeanine, said: that this exhibition shows their brother as a person. But still, there is always a focus on the art.

SBAnd to focus on Basquiat's work is to recognise its formal complexity, and the impressive command he had of every mark he made, each signalling this remarkable conviction.

DBA conviction. True.

SBDo you think Basquiat is a tragic figure? In certain narratives he is mythologised in that way.

DBNot at all. He is just a great artist. The myth helps an artist to be seen, and overseen. So artists who are like Munch and Schiele and Basquiat, Paul Gauguin, the myth often overshadows the real achievements of an artist. And that's what I always try to avoid, any mythification. He is and was just human, like all of us.

Actually, this fact is why his work always needs this kind of contextualisation of the timing when he executed a certain art work, to really speak about why he is positioned in certain ways. Take the symbols he uses that reference the African diaspora. He was always very concerned with everyday racism, and targeted the question of colonialism and slavery. The question of the Black Atlantic and African diaspora was very present in 1984. Before that, he took a more Mark Twain-inspired view of everyday racism. So he had these eight to ten years to really develop his ideas, and of course also transform them.

SBThis goes back to the line in his work, both as a physical mark, and as an ongoing progression of ideas developing through experience and reflected back at the viewer. If you remove his biography, then his paintings speak for themselves; many of them feel like history paintings.

DBI haven't thought about it like that, but that's very true. Some of these really are history paintings, in the way he deals with his subject matter. Like Undiscovered Genius of the Mississippi Delta from 1983—that's a new model of history painting, reclaiming history by collaging different pieces of information from critical historical events together.

SBSpeaking of history, you have recently curated a group show at Almine Rech Gallery in New York, Words Without Thoughts Never To Heaven Go (31 October–16 December 2017). The show explores 'the word as an image and its metonymic relation to the motif itself', and presents work by Basquiat, Juan Gris, Barbara Kruger, Pablo Picasso and Martin Kippenberger, among others. Could you expand on the curatorial concept and talk about how you went about selecting works to express it?

DBWords Without Thoughts Never To Heaven Go focuses on the word as an image and its metonymic relation to the motif itself. The title refers to William Shakespeare—as Ed Ruscha put it: 'a noble quotation that is as timeless as it is poetic'. The starting point of the exhibition is anchored in an astonishing group of rarely-seen early paintings and drawings by Picasso and Georges Braque from their cubist period, introducing words as pictorial elements in modern art, including the first purely textual work of cubism by Picasso: Être ou ne pas être from 1912. From Cubism to Dadaism and Surrealism up to Post-war art, the exhibition follows the increasing importance of words in artworks. René Magritte's iconic work The Treachery of Images (1929), with its statement 'This is not a pipe', is a key moment in art of questioning the pictorial representation of a subject. It opens up the overlap of art, writing and language.

Following the Second World War, artists such as Andy Warhol, Sol LeWitt, Robert Morris, Ed Ruscha and Joseph Kosuth made words one of their main motifs and resources, sometimes claiming them as objects. Furthermore, works by Jean-Michel Basquiat and Martin Kippenberger from the 1980s offer an outlook to the very broad use of words and language in contemporary art. In terms of loans, we are very grateful to have the generous support from several exhibited artists or their estates, as well as from museums such as the Centre Pompidou and private collectors, all of whom kindly agreed to share their invaluable works. —[O]