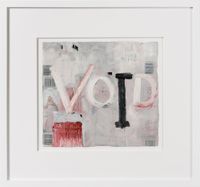

Fiona Hall

Fiona Hall represented Australia at the 56th Venice Biennale. Hall first emerged in the 1970s as a photographer, but during the 1980s moved to using a diverse range of art forms. Her ever-growing repertoire includes sculpture, painting, installation, video and garden design.

The Adelaide-based artist is the sole artist exhibiting at the newly constructed Australian Pavilion, situated in the Giardini, and designed by architects Denton Corker Marshall. Entitled Wrong Way Time

, the exhibition is curated by Linda Michael and presents everyday materials transformed into a collection of complex objects that are both disparate, but connected. The immersive and multi-sensorial exhibition reflects Hall’s interest in museology, and her ongoing engagement with a range of global political, financial, and environmental events and issues. The exhibition will be, in the artist’s own words, “a minefield of madness, badness, and sadness in equal measure”, but it is not intended to be gloomy, nor about dogma; she hopes it might engender a sense of recognition.

Please can you tell me about what will greet those entering the Australian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale?

As you know, Australia is getting a new pavilion. I am working towards an installation in which a lot of components come together. As is often the case, when you are working like this, you don’t actually know until it is all up what the reality of the final thing will be, even though you are living with it in your head and in your psyche.

A fair component of my work is small, and at times quite fragile, and I am a self prescribed ‘museum junkie’—not strictly of art museums, but all sorts of other museums—so that is something that has informed my work.

Within the pavilion, which has almost a square interior, there is another square of cabinetry, which is like a square donut that has two entry points and you can walk into the square and you can look at the work from inside or outside of the square. At times what you see on one side is different from what you see on the other.

The square is not meant to be a dominating factor, but it does configure the space and it sets up a system, which enables me to show quite a broad spectrum of work in different mediums and of different kinds. I rather hope the different works will all interconnect and relate to each other in some way, so the installation is not a set of disparate works, although there is an intended disparity as you often find in some of the stranger museums. There is often a real disparity between [the objects] in a museum, but it all sort of connects. No single one work, or body of work should take precedence over any other.

Exhibition view of Fiona Hall's Wrong Way Time at the Australian Pavilion. Courtesy of Australia Council for the Arts.

Tell me about one of your favourite museums?

One of my favourite museums is the Hunterian, which is opposite the more well-known Sir John Soane’s Museum in London—I think the Hunterian is the more bizarre. The museum holds the collection of John Hunter, a surgeon working in the 1700s. He collected all sorts of specimens and preserved them. So that is a good example for me of the real world museology that has been an influence upon me.

The exhibition in Venice will include forms knitted from shredded camouflage fabric. Please can you tell me about your use of camouflage?

Well, I was cajoled into doing a residency for a month in Sri Lanka in late 1999 with the Australian Asialink Arts Residency Program. I was resident on the estate of their eminent architect, Geoffrey Manning Bawa; he passed away just after I started to go there. I went with a lot of indifference about what it would be like. I had spent time in India and I was a bit sad not to be going there where I had visited a lot and forged very good connections with other artists. But Sri Lanka was a watershed time for me and it changed the course of my work in a number of ways. I completed some very major works there.

At the time, while I was there in late 1999, there was the dreadful civil war raging in Sri Lanka—a war that raged for thirty years. I didn't witness the war directly, but there were suicide bombers in Colombo while I was resident there. There were army checkpoints all over the place; if you travelled around you were repeatedly stopped and papers checked. The thing that really fascinated me was at all these checkpoints on the roadside were concrete bunkers all painted in camouflage; it was bizarre and beautiful.

There was one such checkpoint very close to the estate where I was staying, and it looked like Mondrian had designed it; another one I saw a few years later looked like stained glass. It got me thinking about many things, but mainly about camouflage being a good evolutionary idea in nature, which has been captured by 20th and 21st century warfare. I realised camouflage is a bit like a McDonald's sign; it announces your brand. I started to think about camouflage as a really very beautiful metaphor for conflict. I was thinking of it back then in a colonial/post-colonial way because Australia, New Zealand, India, and Sri Lanka were all under British rule and British colonisation for the greater part of our history over the last few hundred years.

So the idea is really about camouflage as a metaphor for conflict, and it is relevant for a component of my work at Venice that uses camouflage.

Fiona Hall, All the Kings Men, 2014-15. Exhibition view, Australian Pavilion, Venice Biennale 2015. Image Credit: Christian Corte. Courtesy of the artist and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney. © The artist.

There is that very interesting piece of writing by Roger Caillois, the French intellectual thinker, who did a whole lot of research in terms of camouflage. He discovered there were as many camouflaged beetles as non-camouflaged beetles in birds’ stomachs, and he used this to argue that some creatures hadn’t evolved camouflage as a system of defence, but rather they have over-identified with their environment and are driven to mimic it.

That is very interesting. For me in the end, biology and camouflage is all about strategy. It is also about knowing friend and foe, so the whole identity thing is very important. I remember reading that some beetle specialist back in the 1940s was asked if he believed in God, and he said, “Well perhaps, but God must have had a predilection for beetles." There is more variation in beetles than any other living organism. It is huge. I liked that cheeky response. Why have so many designs for so many of them? The natural world is just endlessly inventive. But it is always inventive for a reason.

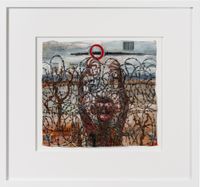

I understand camouflage was a key component of the work you created for the TarraWarra Biennial that saw you working with twelve women of the Tjanpi Desert Weavers collective. Can we please discuss that experience?

Yes. I worked with the Tjanpi Weavers on two ideas. One of them was related to the extinction of native animals, due mainly to pests. The different responses were interesting. One of the women came back in an email and said: “You know it isn’t just the animals that are suffering, it is us too."

My other idea related to the Maralinga Atomic Testing back, which took place in the 1950s and 1960s.

At the beginning of the workshop and when the very touchy concept of Maralinga was raised, it was almost too hot to touch. While some of them were keen to talk about it, some of them couldn’t go there. One of the women had been orphaned.

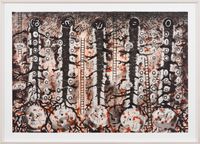

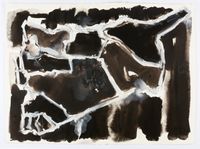

Fiona Hall, Crust, 2014-15. Exhibition view, Australian Pavilion, Venice Biennale 2015. Image Credit: Christian Corte. Courtesy of the artist and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney. © The artist.

Is the work with the Tjanpi Desert Weavers reflected in what you are showing in Venice?

We did two bodies of works, and one of them is in Venice.

There is a section of the Venice catalogue where the women have written pieces and one of the artists—very much an elder stateswoman of that community—talks about Maralinga.

I am so glad I got the Venice invitation and some of their work is going to Venice, because I don’t know if you are aware, but our Prime Minister came out recently because they want to close down communities across the desert. Some of the women come from the communities on the list. The Prime Minister said it was a “lifestyle choice to live out there”. As you can imagine that has angered many of us immensely. But it is also scary because mainstream Australia agrees with him. So taking their work to Venice is political.

Can you please tell me why you used the title Wrong Way Time, for the Venice exhibition?

Well, it would be about eighteen months ago that I received the invitation to represent Australia at Venice. Within six weeks of the invitation, I had to produce an outline of what I was going to do. I knew the installation would deal with—from my own wacky perspective—global conflict, global finances and the environment, with a sense of the madness, badness and sadness of our world. I then decided to call it “Wrong Way Time”. It's a title from the vernacular. It is not a title from some type of scholarly theatrical perspective. I mentioned it to my curator, Linda Michael. And she liked the title and she got it. Back then other people didn’t really get it, but they do get it now.

I came up with the title for a few reasons: one is that there is a considerable number of clocks in the installation. The clocks will be going at random times. Nobody knows what the acoustics will be like.

Exhibition view of Fiona Hall's Wrong Way Time at the Australian Pavilion. Courtesy of Australia Council for the Arts.

Tell me about why you have used clocks?

There is a clock shop close to where I live and I sourced some of the clocks from there. It is only a small shop; there are some truly amazing clocks in there. One of the things I realised when I first walked into its door and spent forty-five minutes talking to the guy in the shop, was the sound. The sound was fantastic. There were all these sounds coming from different directions.

The experience in Venice will be much like my experience in the clock shop, like an audio marker in the space. There are some clocks that are raucous and some that are melodic. A lot of them chime on the quarter hour, and some of them have a classic Westminster sound.

Have you used sound in an installation before?

I participated in the most recent Documenta, and I used a cuckoo clock that I painted. I used that because of the hunting scenes on it. Cuckoo clocks are made in the Black Forest in Germany and this local guy came into my hut—I was one of twenty-four artists who had a hut in this historic place in the park—and he gave this beautiful deconstruction about why he thought the cuckoo clock was so appropriate. It was fantastic. I have done some more installations since then using cuckoo clocks, but not with all of the other clocks we are using now.

So I suppose this a good example of you treading old ground and trying to tread on new ground too?

The old ground is re-configured or mediated.

There are about three works in the show and they are very small works and for anyone who knows my first works using tin with the body part inside, there will be instant recognition. They are only tiny works. These small works are little silvery things that are sort of like jewels within everything else.

One of the fantastic things about museums is the devil in the detail. When you look at somewhere like the Hunterian, it is the way that things which are disparate sort of unfold into each other.

There are three different works made also from the same material, but they are very different works. There is a work that looks like a tunnel, and has LED lights in it; it is very different from the smaller works I just mentioned, but it is also made from metal.

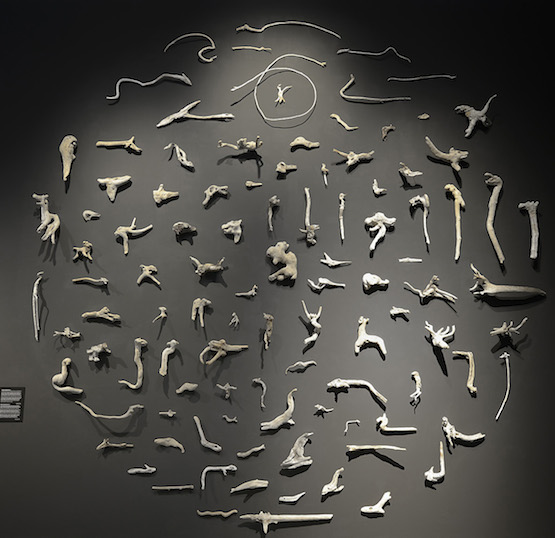

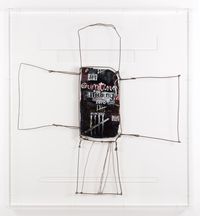

Fiona Hall, Kuka Irititja (Animals from Another Time), 2014. Exhibition view, Australian Pavilion, Venice Biennale 2015. Image Credit: Christian Corte. Courtesy of the artist and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney. © The artist.

Can you let me know more about this tunnel work, and your thinking behind it?

It is about Rupert Murdoch. This is not something I have not touched on before, although I have made a tunnel work before (that work sits in a beautiful museum very close to where I live in Adelaide, the Santos Museum of Economic Botany).

Why Rupert Murdoch?

I don’t want to describe it too much. It is about seeing it. The whole thing is very small and it is based on an old 18th century format that was used back when people were experimenting with optical illusion in the early days of photography and in the lead up to cinematography.

You look through a small hole, and look back through the layers and so it becomes three-dimensional. It is enclosed in one of the cabinets that I discussed before. And it has an LED lighting system inside it that is programmed so the lights do different things over a minute (because a person’s attention span is not very long).

So I am using metal in that particular piece, not to refer to earlier work, but because of the material.

Fiona Hall, Mamu and Frog / Mamu munu ngaanngi from Kuka Irititja (Animals from Another Time), 2014. Spinifex grass, emu feathers, military fabric, paint, aluminum, zip, tin can; 55 x 36 x 36 cm, tin 29 x 27 (diam.) cm. Image credit: Clayton Glen. Courtesy of the artist and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney, Australia. © The Artist.

What comes first for you: the ideas or the material?

It varies. As you go through life you find you have some sort of history about the way you work, which can be focused on material or on subject matter and you realise a lot about your own predilections and also your own abilities.

I have a history of working in photography, and for a number of years I studied painting. I am all over the place in many ways in my use of materials. But that has an advantage. I like the versatility of using a range of materials. But I wouldn’t use the material unless it was appropriate for a work. Generally the material carries the evidence of its own history, which it brings to the work—that is an important part of the work.

The tunnel thing I have made is a bit of an aberration because the material for that work (tin) was, for a lot of reasons appropriate, but it doesn’t carry conceptual weight; the ideas behind the work are not related to the material.

Is there anything that has come out of this Venice experience thus far that you can see leading to somewhere else in terms of your practice?

It is too early to say because I haven’t yet been through the mill of showing in Venice. So I have no idea of what to expect there.

But we earlier discussed the project with the Tjanpi Desert Weavers and there is another project with them brewing which should be interesting. I had an invitation fairly recently—because it is the centennial of the First World War—to contribute work to a show about Trench Art. Trench Art is very much about the things the soldiers made in the trenches to while away the time and using whatever material was available: there are beautiful carvings from bullet casings. The Australian War Memorial has a collection of Australian works. I was asked to participate, along with twelve other artists, and make work referring to the Trench Art in the War Memorial museum. I said I would participate if I could work with some of the Tjanpi Weavers. There is a workshop being organised that is taking place in August this year. I have no idea what will come out of that. I really loved working with them. They are enormously creative and I am keen to do it again.

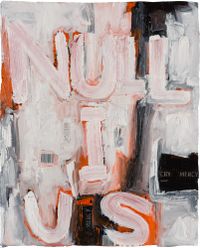

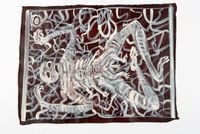

Fiona Hall, Manuhiri (Travellers) 2014-15. Exhibition view, Australian Pavilion, Venice Biennale 2015, Image Credit: Christian Corte. Courtesy of the artist and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney. © The artist.

Are there any other specific works in the show you would like to discuss?

There is also a work from New Zealand in the show. These days I go camping with a couple of good friends of mine—some art types—up the North East Cape, which of course is mostly Māori land. For the last five years I have been going and walking along the beach there and picking up wood that looks zoomorphic. The work has an allusion to environmental degradation. There are a few lines that I wrote in conversation with a local Māori family, and these have been translated into Māori for the catalogue.

That is one example of a body of work that will be wall work, but which will hopefully carry its weight conceptually and fit within that museology framework where there is a clash of materials, provenance, concepts, but which all come together. How successful that will be remains to be seen.

Much of your work has political undertones. To what extent do you define the success of your work by it effecting some sort of change in the viewer?

I would say it is probably more about engendering a sense of recognition.

Back when I had to write my outline, just after I received the invitation to do Venice, I wrote about the “madness, sadness and badness of the world”. I said the installation would be dark, but that doesn’t mean it will be gloomy. I do look back eighteen months ago, when I wrote that, and think: “Fiona, what was so mad and sad and bad about the world, compared to what it is now?” I think people were originally taken aback by the themes. But now I don’t feel I have to explain these feelings and I suspect these feelings will be reflected in a lot of the other work that is done for Venice.

We are all captive to the time we live in and experience. I guess I would like people to recognise, in a sense, that despite diversity we really are connected. If we live in denial of those connections then the world really is a gloomy place.

One thing my work does in terms of a strategy is that, like nature—which is all about strategising and seeming to be playful and gleeful—it sets out a disarming kind of methodology where people are drawn into something by certain hooks in the work and then they find themselves responding. It is about presenting a state of affairs on multiple fronts, rather than a show that is about dogma of one kind or another.

I don’t think an artist can change the world with their work, but I do think artists are game changers. I think artists are like litmus paper, not just visual artists. Actually artists and scientists both are like litmus paper—they give a sense of where things are. —[O]