Hyungkoo Lee: Seriously Fake Science

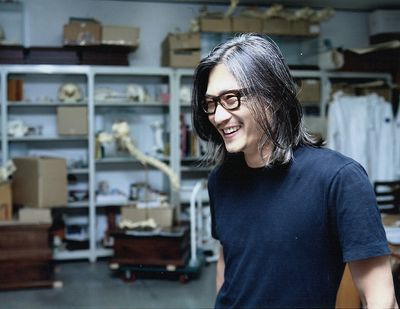

Hyungkoo Lee. Courtesy the artist.

Hyungkoo Lee. Courtesy the artist.

Korean artist Hyungkoo Lee's exhibitions evoke a scientist's lab or an archaeologist's workshop, often equipped with outlandish gadgets, skeletal or anatomical models in vitrines, or a desk with incomplete skulls, brushes, and notes. Yet his wearable devices, drawings, and sculptures hardly depict real-life subjects—they are chimeras borne out of scientific research and the artist's imagination. 'ANIMATUS' (2005–2007), for example, is a series of cast resin sculptures that depict the skeletons of widely beloved cartoon characters. Though the long ears are missing, the distinctly huge buck teeth of Lepus Animatus (2005–2015) belong to Bugs Bunny, while Donald Duck's skeleton struts about as Anas Animatus (2006).

The uncanny, sometimes startling aesthetic that defines Lee's practice was on full view in The Objectuals, his first major solo exhibition at Sungkok Art Museum, Seoul, in 2004. Among the works on view was A Device (Gauntlet1) that Makes My Hand Bigger (1999), a wearable arm fashioned from plastic bottles that resembles a detached robot limb with three bulky sockets at one end for placing fingers. The C-print Enlarging My Right Hand with Gauntlet 1 (2002) shows Lee's invention at work: when one puts it on and pours water inside, the right hand appears larger, the fingers thicker. Other works included portraits of people wearing helmets that magnify their facial features. Altering Facial Features with Device-H5 (2003) zooms in on the eyes, while Altering Features with BH3 (2003) focuses on the mouth to the point it becomes abnormally big, treading a fine line between humorous exaggeration and nightmarish visualisation. The exhibition set aside a space for Lee's laboratory, complete with a white lab coat and a display box for gadgets—the workplace of a mad scientist, obsessed with strange optical instruments.

Lee's concern with body enhancement partially rose out of his experiences of living abroad. After completing his undergraduate studies at Seoul's Hongik University in 1998, he relocated to the U.S. to pursue a master's degree at Yale University. In his new environment, the artist felt that he, as an East Asian man, was physically smaller than the men around him, with works like Satisfaction Device (2001)—a leather belt with a tube that makes the penis look bigger—pointing to his inferiority complex. Around this time, Lee also created the contraption he titled A Device for Walking Backwards (2001), which helped him to learn to walk backwards; a work that was borne out of his desire to reorient himself to unfamiliar environments.

Lee's exploration of the human body also concerns its mechanisms, with works that involve experimentation with movement. Creeper (2010), for example, brings the artist down to ground level, making him lay face down on a longboard with handles at the front to navigate. Aside from physical mechanisms that define how bodies move and perceive space, the artist is also interested in subverting how bodies are classified. 'Face Trace' (2012), which was also the title of his solo exhibition at Gallery Skape, Seoul, in 2012, consists of 12 busts depicting different facial types. Lee began with constructing them according to existing racial categories, but completed them by inserting fragments based on the moulds of his own face—thus creating entirely new hybrids.

In his upcoming solo exhibition PENETRALE at P21 in Seoul (16 October–30 November 2019), Lee is to showcase some of his recent and new works. One is X (2019), an installation featuring what resemble bone fragments, spheres, and arrows on a three-dimensional grid. The artist is also currently participating in the group exhibition Show Me Your Selfie at Aram Art Museum in Goyang (17 July–6 October 2019). In the conversation that follows, Lee discusses the inspiration behind some of his works, the processes he employs, and his interest in the human body.

SPLet's start with your installation X, one of the new works in your solo exhibition at P21 in Seoul, PENETRALE. In one interview, you talk about playing a different role when working on each of your works—a pseudo-scientist for 'The Objectuals' (1999–present); an archaeologist for the 'ANIMATUS' series (2005–2015); a horse in Measure (2014); and a rock climber for Kiamkoysek (2018). Did you also have a role in mind when creating X?

HLX is the first work in a new series, which involved taking an enlarged skeleton structure—evocative of fossil fragments in the process of restoration—and visually materialising it using an imaginary theory. Psyche up Panorama, the second work in the new series, is comprised of shattered fragments and installed on a wall, floor, and ceiling of one room at P21, while X is installed in the adjacent room.

My approach to art is similar to method acting, allowing me to become immersed in my work. For PENETRALE, I employed my general interest in anatomy, as well as other sciences, including physics, chemistry, and astronomy. Because this new series is an extension of my previous work, it's difficult to say whether I played a specific role.

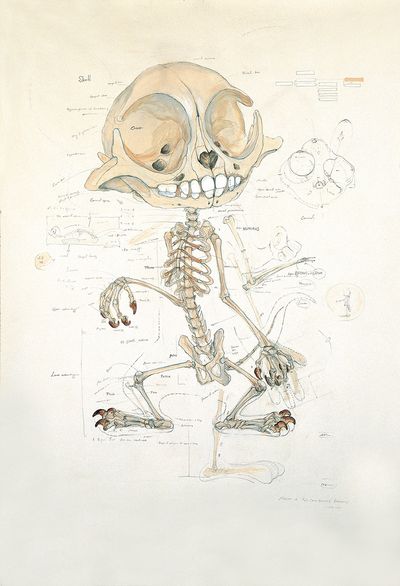

SPWorks involving skeletons look especially difficult to design and construct, and there are often drawings—such as A01 (2005) and A10 (2006), which are part of 'ANIMATUS'—that describe them in detail. I assume drawing is a significant part of your practice?

HLThe cartoon characters that I selected to create the series 'ANIMATUS' have all been anthropomorphised. In order to give them the upright posture that is unique to humans, their spines had to be curved in the opposite direction. The joints in their wrists and their ankles also had to be reimagined, because cartoon characters usually have fewer fingers and toes than their natural counterparts. The eye sockets were also reimagined to accommodate eyes that have been blown out of proportion.

Drawing is an important means of satisfying such physical conditions and obtaining anatomical knowledge. When sketching, I first draw an outline of the character on a 1:1 scale to its three-dimensional size. In the outline, I draw the bones of each part, and when the sculpture is being created, I refer to human and animal skeleton models for additional details. Many of the drawings that I exhibit are not study drawings; instead, they have been re-created as part of the sculpting process, so that I can gain further anatomical knowledge. The sculpture-making process basically follows a traditional method. Individual bone parts are made from clay, cast in resin using silicone moulds, then painted and put together after the initial sanding. Every step of the process is carried out by hand—I don't make the drawings with CG.

SPPseudo-sciences have appeared throughout your practice. In The Objectuals, your first solo exhibition at Sungkok Art Museum in 2004, you displayed the laboratory where you developed your devices; while the 'Face Trace' series (2012) references physiognomy or face-reading. How did you come to develop such interests?

HLMy 'scientific' experiments are fake, yet they are carried out seriously; I'm not a specialist in these areas, I'm only interested in them out of curiosity. I enjoy the euphoria that comes when my wacky experiments come to life and produce unexpected results; they are connected to one another as a series and multiply like the branches of a tree. My thoughts remain mixed, like a diagram of intersections, until that moment when they meld together and become art.

SPPersonal experiences largely influence your work. Where else do you draw inspiration from, or are all works somewhat autobiographical?

HLMy works are largely autobiographical because they are influenced by my environment, daily life, experiences, and learning. A Device (Gauntlet1) that Makes My Hand Bigger (1999), for example, was inspired by an experience I had in New York when I was standing in a crowded subway and began comparing the size of my hands with those around me who were holding the grab handles. I felt like mine were small in comparison to the hands of other people.

SPOne work you made in the U.S. was A Device for Walking Backwards (2001), a contraption that helped you learn to walk backwards. How did the idea come to you?

HLIt's easy to feel disoriented in a new environment. For example, when trying to drive on the opposite side of the road in countries such as the U.K., Hong Kong, and Japan; or using a knife and fork to eat. Measuring weight and length in different units when sculpting is also awkward.

In order to overcome such confusion, I felt I needed to re-adjust my senses through learning or repetitive training. Accordingly, I came up with a device with small mirrors attached on both sides—like the side mirrors of a car—that I could wear on my head to practice walking backwards, like a child learning to walk for the first time. The first few days were stressful and I could feel the muscles in the back of my legs—the ones that had not been used often—developing. I got used to walking backwards—so much so that I could walk up and down stairs with ease. After two weeks, I could confidently run backwards. Through this experience, I imagined how my body might be able to develop to the point where I would no longer need mirrors. It was fascinating to document how my senses changed and adapted over the course of the process.

SPThe human body often undergoes a process of alteration in your practice, ranging from magnification and addition to integration. There seems to be a desire to go beyond the human body's natural state.

HLI have a veneration for the human body and deploy a sculptural approach. I exaggerate or distort a subject, bring to life fantastic images, and explore new physiological movements through experimentation. In re-recognising the body, I venture into an unknown world; as an artist, I also investigate 'the human', but it is not easy to explain or express succinctly.

SPIn Measure (2014), a single-channel video, you are seen wearing a contraption inspired by the hind legs of a horse (Instrument 01, 2014), and learning to move with it. The exhibition, which was also titled Measure at Gallery Skape in Seoul, also presented an environment reminiscent of a stable, including objects resembling bridles and hurdles. What prompted your interest in the horse?

HLIn my 2010 solo exhibition Eye Trace at Doosan Gallery in Seoul, I presented works that track and investigate the perspectives of other organisms, like animals and insects. The 2014 show MEASURE began as an extension of Eye Trace. An individual's perspective is closely related to the movement of the body.

While I was investigating the horse's perspective, I became fascinated with its movement. I was in the process of studying and imitating them when I came across the sport of dressage. It intrigued me that the dressage test is comprised of multiple stages of movements and that the rider receives higher scores when their movements are synchronised with the horse. In Instrument 01, I wear a set of equine hind legs and assume the roles of both the rider and the horse in a performance reenacting the Grand Prix Dressage.

SPHow did the idea of working with cartoon characters in 'ANIMATUS' come about?

HLThe missing fingers and magnified hand and arm in A Device that Makes My Hand Bigger (1999) have a cartoonish quality, which inspired the arm in Untitled (2001). Cartoonish elements continue in the series of works that show me wearing a helmet comprised of convex lenses, which exaggerates my facial features (Helmet 1, 2, and 3, 1999–2000). Character (2002) is inspired by these previous works and shows a skeleton with fewer fingers and toes than a normal human figure, and a skull that is too large for its body. These earlier works led to the development of 'ANIMATUS'.

SPYour practice also includes performance, where you activate devices in works such as A Device for Walking Backwards (2001) or Mirror Canopy (2010). Was it the body alterations or performance that came first?

HLI create devices for experiments, and I show them in exhibitions or document them as photographs. When performances are deemed more effective, however, I stage a performance and film it.

Do you think your work might be unsettling for some people?

Like most things in the world, there are those who love it and those who don't. —[O]