Manal AlDowayan: ‘Everyone wants to define the Saudi woman’

Manal AlDowayan. Courtesy the artist. Photo: April Morais.

Manal AlDowayan. Courtesy the artist. Photo: April Morais.

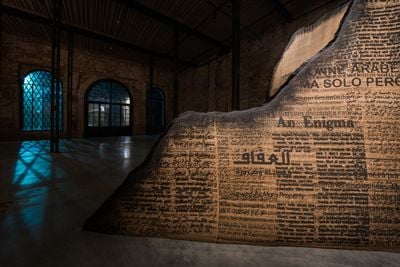

The past year has been a busy one for Manal AlDowayan, who, with curators Maya El Khalil and Jessica Cerasi, is representing Saudi Arabia at the 60th Venice Biennale.

Last May, AlDowayan staged a performance, From Shattered Ruins, New Life Shall Bloom (2023), at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, for which she invited the audience to destroy porcelain scrolls by crushing them.

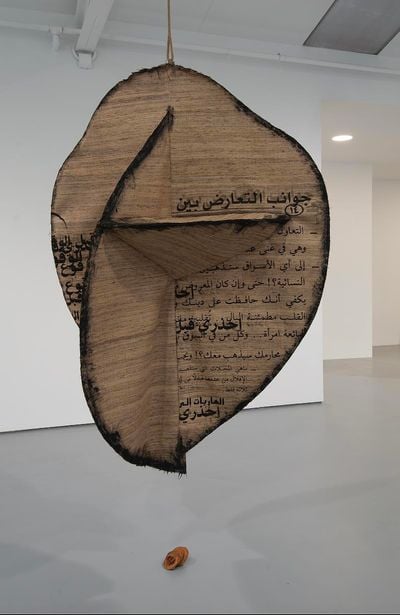

Placed on top of cylindrical totems covered in fabric, the scrolls incorporated fragments of texts referencing language that subjugates women. Sourcing narratives from U.S. religious literature and newspaper articles, social media, and the Guggenheim's archives, the performance extended an earlier series by AlDowayan, 'Just Paper' (2019), in which she focused on texts about gendered notions of propriety, marking an expansion in her references.

The burden of representation is high for contemporary artists in Saudi Arabia, as it undergoes a series of economic and social reforms impacting an art scene that has exploded onto the international stage in recent years. In her search for self-definition in this radically changing context, AlDowayan has been thinking through the notion of intersectional solidarity via collective gestures and participatory works.

Since the early 2000s, AlDowayan has delved into how Saudi women are understood and positioned in public space, examining rigid notions of belonging to reflect on narratives and histories that are often obscured.

Her recent exhibition, Oasis of Stories (2024), presented as part of AlUla Arts Festival, demonstrated this process with a collaborative approach. AlDowayan ran workshops with people in AlUla who created over 700 drawings of their natural environment, homes, and rituals. It serves as a prelude for AlDowayan's large-scale permanent installation, slated for completion in 2026, at the desert sculpture park Wadi AlFann in AlUla's oasis region, as part of a project led by Iwona Blazwick and featuring four other artists (Agnes Denes, James Turrell, Michael Heizer, and Ahmed Mater).

On the other hand, AlDowayan's concurrent Alula exhibition, Their Love is Like All Loves, Their Death is Like All Deaths (9 February–23 March 2024), showcased questioning of a broad arc of ancestral traditions in AlUla, situating Saudi's nation-building narrative within the lineage of the ancient Lihyan, Dadan, and Nabataean kingdoms. There is a maturation to AlDowayan's work in this existential questioning of one's place in history, which culminates this year in Venice in her abstract archive of geological time, movement, and women's voices.

In this conversation, AlDowayan discusses the influence of Saudi Arabia's histories, cultures, and geographies on her work and worldview, defining her own 'voice of the Saudi woman'.

NKCan we start with how your performance at the Guggenheim came about, and tap into the wider feminist discourse behind it?

MAWith every artwork I make, I need to consider who the audience is and where it is placed, as well as what am I saying in this space. I didn't want to self-Orientalise or double down too much on the sense of othering that we experience as Saudis. I arrived in America to find a place that is slowly regressing, reversing the rights of women over their bodies. I wanted to address how women's bodies are controlled without othering America in turn.

As soon as I touched down in New York my Instagram feed transformed. For the first time, my algorithm shifted to show ads about butt lifts and the menopause stomach. I used some of these, along with my research in the [Guggenheim's] archives and nearby newspaper agents on perceptions of women, to create a series of totems and scrolls printed with covers from religious books, akin to those in my solo show, Watch Before You Fall, at Sabrina Amrani in 2019.

This time I included content from U.S. fundamentalist literature, such as 'how to please your husband' or 'be a good wife'. I also incorporated language that surrounds Arab women, like references to how offensive veiling was on beaches, or how they are described as 'oppressed, depressed, and repressed'.

I wanted to address how women's bodies are controlled without othering America in turn.

The final work was both participatory and instructional. For me, the unknown element in participatory works is the most important part; you establish certain structures and see what happens. I asked the attendees to first observe the work for an hour. There was an incredible silence. Then I told them to crush the scrolls, which was rather frightening for museum-goers not used to touching art, let alone breaking an artwork in the heart of an institution dedicated to its preservation. There was the sound of almost 1,000 scrolls being destroyed, after which we heard sighs of relief. It was a great success—around 750 people came. Change is in our hands and if we unite, we can all rise as women.

NKUndoubtedly, it's a very different moment for Saudi women, which is perhaps relevant to the broadening of perspective. How are you processing the changes?

MAWe have made huge leaps. The gap between me and my mother is beyond belief, and this is just within one generation. My experience is like a myth for my 12-year-old niece—there are surreal gaps. Our traumatic memories became bedtime stories.

When I was developing this project, I was reading Rafia Zakaria's Against White Feminism (2021), which argues how this is a movement that is meant to empower women but is not always inclusive. Defining what a liberated woman is in a Western context comes with specific cultural, sexualised structures. Feminism is a loaded term that has been wrongly used against Arab women, for example, which is why I don't call myself a feminist. I say I stand in solidarity with women. There has to be more recognition in how we approach collective care.

That said, I'm not always focused on women. As a human, I swing between different concerns. My 2020 land artwork for Desert X, Now You See Me, Now You Don't, was about the environment and the scarcity of water.

NKHow are you looking at the notion of collective memory in relation to the large arc of history in your recent exhibition, Their Love is Like All Loves, Their Death is Like All Deaths?

MAThis exhibition was a culmination of my experience encountering AlUla, which really transformed me. I first visited in 2012 and have been 42 times since. The work takes the form of a labyrinth because I wanted to create a sense of discovery, of wanting to keep going back in case you missed something—which is how I have experienced the place.

In school, we were not taught the history of the Nabataeans and Lihyanites there, who we are still learning about through archaeology. It's a huge shift in the understanding of both Western and Islamic history—their ruins create a narrative of human history beyond the borders of nationhood. The title is meant to differentiate the past from the present, but we are all part of one narrative. This exhibition feels like an archive that enables me to understand who I am and where I belong.

When I learned that the Nabataeans lived a difficult but luxurious life with the time to carve these palatial tombs into whole mountains, it impacted me as an artist. I felt I needed to show this work for the community of AlUla—they are the continuation of the story—and before my Wadi AlFann land art project, which is supposed to last a century. So, we are leaving an imprint next to the tombs and sculptures left behind by another people, who looked at the same ruins, thought about what or who came before, and wrote poetry.

NKThe show also referenced elements of your earlier works such as the doves from your 'Suspended Together' series (2011), which were inscribed with travel documents women required with permission granted by their male guardians, and clippings from Crash (2014), which documents women schoolteachers who died in car accidents at a time when they couldn't legally drive. It's incredible to understand this context now.

MAAt the beginning of my career, all I could think of was myself and those in my surroundings. Self-definition is very difficult in this part of the world, where we are just beginning to record our intangible heritage: our culinary, craft, dress, and dance cultures. This makes it easier to centre, look towards the future, and make plans.

I grew up in a very women-centric environment in Saudi that was reinforced by the gender segregation. We used to gather in women-only schools and banks, but we were not helpless. We took family decisions together. I like to call our women-only spaces a counter-public with its own politics and room for negotiation. These were spaces that empowered women because the male gaze was absent.

The power of having space for your body and voice can't be understood unless you experience it in this way. We are currently moving into visibility in the public space, which is excellent, but it does not mean the journey is over. We have to be aware that this is a transformative time and that we, women and men, have to think about how we will negotiate our bodies, voices, and presence in this new arena. It's an important moment in the history of both the nation and its women.

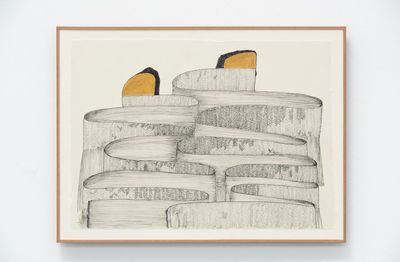

NKIt is the first time you showed drawings from 'The End Is But a Beginning' series (2023), which show spiral forms that ascend. I didn't know this was part of your practice.

MAI've never exhibited this form before. They were inspired by doors of AlUla's tombs, which have the feeling of the end—the door you enter upon death—but the Nabataeans didn't believe in an end. They dedicated themselves to the afterlife, the next stage of life.

I started thinking of the small doors of the tombs in relation to the grandeur of their empty architectural container, which we fill with politics and ideology because we don't know what was there. It was interesting for me to think about this structure that was created for a transition. Since I was thinking of materials that are inherited and mastered over generations, I used Japanese gold, ink, and washi paper, which is a UNESCO intangible cultural heritage object.

NKIt's also the first time we are seeing actual desert roses—a longstanding fascination of yours—contained within smaller clay sculptures that trace the imprint of fingers, which feels like a new direction in your work.

MAI wanted to leave behind a gesture of touch. The desert roses were initially inspired by the graphic language of religious books written by men, where roses often symbolised women. These roses were detached from their stems, as if waiting to wilt.

I grew up with geologists in Dhahran, where the desert rose is endemic and the sand is unique—it includes gypsum that crystallises. The desert rose only forms after strong rainfall in April, in extreme heat. Now is the season to find them everywhere. They can withstand so much; this is the quality I think is more symbolic of the Arab woman.

NKYou often collaborate with and work through your community, like an ethnographer gathering images and stories and responding to them. In your pavilion at Venice, Shifting Sands: A Battle Song, you delve deeper into the role of the collective voice and song. Where does this impulse come from?

MAI've been obsessed with collective singing for many years. When I did a Delfina residency, I met someone from an organisation called Sing Up, who do group singing around the country. The experience was so elevating that it stuck with me. I wanted to do the same in my country.

During my fourth or fifth year at Aramco, where I worked from 2000 to 2010, I went on a field trip to Rub' al Khali desert (the 'Empty Quarter') with the geology group. Thirty of us sat on the edge of a sand dune, pushing back against it, and the dune began to hum. I found that there are only a handful of deserts in the world that have singing dunes and Rub' al Khali is one of the loudest because of its scale and dryness.

After I was nominated for Venice, I looked back at my old notebooks on fantasy projects. I feel the universe or God guides me in that way—some projects are not meant to happen at certain moments. My pavilion has speakers and a central, twisting sculpture. There are three gigantic desert roses, the largest I've ever made, and they turn in on themselves. I decided to use field recordings of the dunes as our song. I'm referencing the battle song of the Al Dahha dance from the northern and southern regions of Saudi Arabia and also Palestine and Jordan.

The legend behind it is that the men made these animal sounds like roaring lions because they wanted to scare off a Persian invasion with a much larger army. The dance features men standing shoulder-to-shoulder, making guttural sounds, and a woman dancing in the centre. She is the motivator, holding the sword as if to say, 'If you fail, I will fight and join this army too.'

Everyone wants to define who the Saudi woman is and what she stands for and I think it has distorted our own self-image.

Although the dance has evolved to include only men with a poet in the middle, when I was doing my research in AlUla, I was invited to weddings in which women performed this dance. The most beautiful woman of the village would wear a bejewelled bisht [traditional cloak] and dance in the middle. That this still exists after thousands of years has inspired me a lot. It is a way of saying we are many, we are more than you think. That is the power of the voice, and this is why I've been doing participatory work all my life.

The work is about social change and the disappearance of women from collective memory. There's the idea of a lineage, a tribe, and heritage. I'm creating new battle songs that question the women's condition in Saudi Arabia as one of extreme external pressure. Everyone wants to define who the Saudi woman is and what she stands for and I think it has distorted our own self-image.

NKThis community-driven research feels like a more abstract way of recording the unofficial histories of women, compared to your work in Tree of Guardians (2014), for example, when you asked Saudi women to draw their family tree based on matrilineal lines and names that would eventually disappear. What was your process like?

MAI began my workshops for Tree of Guardians and Esmi – My Name (2012) in Khobar and Riyadh in the early days and I have returned to the same locations that hosted me when it was not easy. I gave over 1,000 women headphones and asked them to harmonise to the recordings of singing dunes as we hummed together.

Then I showed them articles written about Saudi women in both Arab and Western media to get them to respond to the cacophony of noise defining us. I asked them to write and draw as if they were the central poet of the dance, the instigator of this new moment. I selected some of the pieces; this is how we produced the song together. Some of the 500 drawings will be included in a book, and also on my desert rose sculptures because I really want you as a viewer to use your body and find the voice of the Saudi woman. Sound occupies both space and body.

I've turned this male-only form into female-only. Saudi women are normally invisible and that's why I've sounded them. It is also relevant to the theme of the Biennale, Foreigners Everywhere, and expands on what I did in New York, by staging a refusal of othering and external definitions.

NKIn a way you've come full circle by looking at outward perceptions, only to go deeper within your community.

MAWe are not emigrating or in a new country, but these perceptions are shifting as we re-enter the public sphere. The sand dune has condensed compact earth, but the top layer moves and shuffles back and forth, which I feel is a symbolic gesture towards what the Saudi woman is going through. —[O]