Mandy El-Sayegh: Productive Ambiguity

Mandy El-Sayegh. Photo: Abtin Eshraghi.

Mandy El-Sayegh. Photo: Abtin Eshraghi.

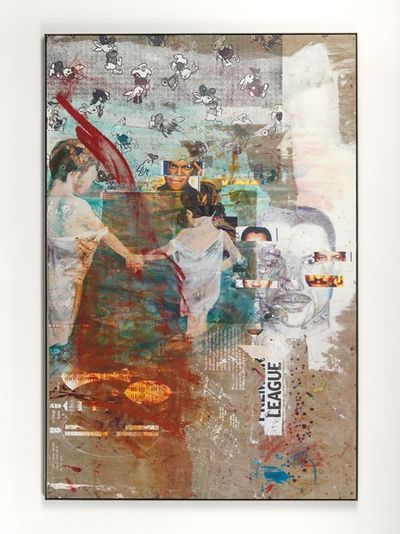

Moving across installation, painting, drawing, and writing, Malaysia-born and London-based artist Mandy El-Sayegh explores the political, social, and economic complexities of humanity, using a mosaic of information—from advertising slogans and pornographic imagery to newspaper articles—that she subjects to processes of layering, erasure, and obfuscation. This practice originates from an interest in part-to-whole relations between science and philosophy, whereby fragmentation can lead to the creation of new meaning.

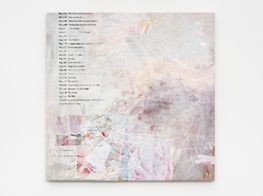

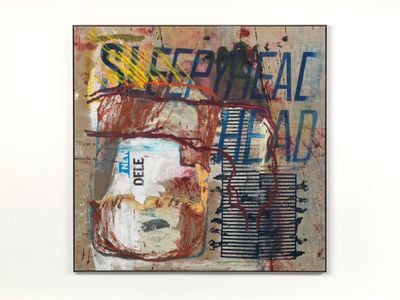

Generating meaning is thus a fluid process; one that remains in a state of flux, but that is pinned to symbols and signifiers. This tension between concrete information and its contribution to new meaning was explored in Cite Your Sources, El-Sayegh's first solo exhibition in the U.K., at Chisenhale Gallery in London's East End (12 April–9 June 2019). The exhibition included the artist's ongoing 'Net Grid' series (2010–ongoing)—large-scale paintings of layered text and imagery that is interrupted by hand-painted grids as a literal reference to the net as catching information. El-Sayegh's use of the wet-on-wet technique, of layering paint atop freshly painted surfaces, recalls the saturation of information—accentuated in this exhibition through the pasting of pages from the Financial Times across the floor and walls. Images and blocks of text once more approximated the grid, while overlaid calligraphy in Arabic from her father's practice, along with other abstracted information, pointed towards the mutability of language. The flesh-hued tone of the paper, meanwhile, recalls the body and its entanglement in the political landscape.

Against the backdrop of Hong Kong, El-Sayegh's most recent exhibition at Lehmann Maupin holds particular significance (Dispersal, 11 July–23 August 2019). The city's protests against a controversial legislative bill that would allow residents to be extradited to mainland China entered their tenth week on 12 August, with thousands of protestors occupying the airport over alleged police brutality on the Sunday. The selection of 'Net Grid' paintings on view in this exhibition are placed against a backdrop of pages from South China Morning Post pasted across the walls of one gallery. El-Sayegh's choice of a local newspaper that is published in English addresses the frameworks of nationality, culture, and society that are prevalent in her practice. In an interview with South China Morning Post held after the opening of her show, El-Sayegh cites her heritage—being half Palestinian and half Malaysian Chinese—as resonating with Hong Kong through her mother's connection with China, leading her to realise that she has 'the same tension, the same urge to split from a body'. 'In Hong Kong, it's two systems. In Palestine, it's the two-state solution. In Britain, it is leaving the body of Europe'.

The following conversation is an edited, and structurally adjusted transcript of a public talk that took place between the artist and Para Site's deputy director Claire Shea ahead of the show's opening, traversing topics of the fragment, the body, and the mutability of language.

CSCould you start by describing your show in Hong Kong at Lehmann Maupin, Dispersal?

MESHong Kong spaces are smaller, so I was thinking about how to express this complexity in two gestures. In these two spaces that are really small, I was thinking about the spectrum of figuration to abstraction, so one space is very material, with latex on the floor, and the other space is more about painting and figuration.

CSAre the parameters that you are working different across the various series you make, or do more general rules apply?

MESThere are arbitrary units of measure, and then the grids are 225 by 235. The latex units are roughly the size of a torso, because I don't think as a painter of the composition—I think of spreading. Those parameters do change depending on the space.

CSWhat about the title of the show, Dispersal? It has a positive and a negative connotation, with multiple senses somehow.

MESI'm thinking about this idea of an explosion, and a way to kind of start again from that. After an explosion, you have fragments that you can recombine to make a new body. When you get anxious it can feel like your body is dispersing, and weirdly enough, trauma can be a bad thing, but from that you can also reform. So I'm thinking of a reformation of parts.

CSThis idea of reforming parts relates to the different series that you work within, and how they relate to one another. Could you talk about that?

MESAll the series of works have this relationship with the fragment, and how to give the body to the fragment and cohesion. So there are the 'Net Grid' paintings, which came out of a grid system, and a net is something literal that catches things in the sea. I'm thinking about figuration and abstraction on the spectrum, so that's in the realm of painting. There are these table vitrines that I have for my collection and my archive, which is also looking at fragments, and then the paintings that deal with this archive or artefact in the visual field. Paintings, tables, skins—those are the main things.

CSWhat does your archive look like and how has it developed?

MESIt sounds really serious when you call it an archive. I'm more of a hoarder. You think of a collector or someone who does something consciously, and discerningly. Whereas a hoarder is doing things for different reasons—it's a compulsion that's pathological. My mum is here in the audience and she knows how messy my room was as a child, and how I couldn't throw away my things because they had a special meaning to me. This is a way to formalise that compulsion, so the archive is not something that's conscious—it's just part of being. I make sense of that through distillation and through forms and meaning, such as a painting, or sculpture, which constitute fragments of my subjectivity, and that mutates and changes and can be reassembled in different ways. I can disassemble everything—I can take a painting off a stretcher and cut it up if I feel it's no longer resonant. I like that each work is a unit that I can disassemble.

CSWhen you disassemble works, do they always stay within the same format or medium, or do they move between?

MESYes, they can, they always do. But I always try to give myself limitations, otherwise it can go on forever. Like the spread, the mess, the kind of never-ending spill. So a table will stop the edge of the spill—what I call a free association. If you go to a shrink, as in the Freudian tradition, the analyst is reticent and doesn't say much and you just talk. You might end up hating the sound of your own voice, but this free association speech can go on forever until they say, okay, 45 minutes is up, or something. They stop you at a relevant signifier. I could liken these parameters as the stopping of analysis. All the grids are 225 by 235. The smaller ones are studies, but they're not of the bigger series. The tables stop the flow of a kind of session. So I'm always trying to stop myself—that's where the curator comes in.

CSWhat are some of the mutations that happen in your works? Overall, there seems to be formal similarities.

MESI get very bored if I don't learn something. It's kind of a very formal investigation of the figure-ground relation—like how something can work together if something recedes or comes forward, in terms of meaning and aesthetics. A simple structure like a primed white surface and a net on top, for example, is a consideration of these fragments of linguistic material and how they can disappear into the composition. I'm thinking about erasure. What I've done over the last few years is when there's a certain relation, I'll introduce another element so there's more matter that takes longer to erase or bring forward. There's more stuff and more colours now, whereas before I always said, 'No: white and red.'

Seeing and reading are very different things. Reading the news is very different to looking at something, but they're kind of related to absorbing information—different registers of seeing and absorbing different things.

I include fragments of conversations, headlines, materials; it might even be a rag I've used to wipe the surface of the painting, and I like the stain of it. My brother just gave me this amazing pencil case that he had scribbled on in lessons and filled it with all the squiggly brain-like lines—I like that. I don't know why I like it, but it has an energy on top of it. It can be really nonsensical stuff, but naturally it becomes loaded when you put it on other material.

CSYou seem to pull a lot of materials from your personal life and your relationships with your family, and you juxtapose those with other elements from popular culture. Is that at play in all of the works?

MESI think that idea of super-specificity, which is really solipsistic and internal, and can relate as a fractal with a wider connective, is really important. I remember before someone said my work is like pop, and I thought, oh that's not good. But depending on the reading of it, it can be an archive and also disperse into this really dumb thing, or really clever in how the elements work together. It's moving in and out of something very specific to very global, and how that signifier translates globally as it moves. It's just expressing its pliability. This micro-macro is very important. I can only work from my own material, right? I can't work from the outside in.

CSThe newspaper is a very prominent feature in a lot of your work. How did that interest come about?

MESI was thinking about ground as an idea and noise and the incubation of noise—this idea of collecting and something affecting your thinking that gets embedded into your thoughts through the pervasive circulation of information.

More specifically, it's also about lifting from my father's practice, which consists of calligraphy on free tabloid papers, papers on the underground in London, or any surfaces that he'd encounter—it could be the inside of a cereal box, or any attractive surfaces for a pen, and he would do this work to strengthen his hand and then he would throw them away. I thought this was an apt exercise—he's not thinking about the meaning that's being created, but the meaning is being created through the chance encounter of surface and these words that are sometimes made up or changed, because it's more about shape and gesture. His approach is very formal in that sense and not context-based or intentional. This idea of intentionality is a big question in my practice.

CSText features quite a lot in your work as well—is there a relationship to your father's practice in terms of text and language?

MESIt's more subconscious. I lifted his methodology; I like the idea of how he amends words for his purpose. If he was writing Arabic, he would modify it. Often if poetic phrases are taken from the Quran, he wouldn't want to throw away the sacred script in the bin, which is what he did before I started collecting them. The English he would use would include really strange phrases that didn't make sense, or nice English names with a nice shape—like Vicky has a nice shape, with the 'v' and the 'k' when it's done in italics. It's about how words can take on their own life, independent of the message they're conveying, and that mutation can have its own surrealist logic—it's also about treating language as a kind of material; treating language as mutable and plastic.

I don't understand both English and Chinese. When my mum goes to Malaysia she collects Chinese calligraphy done on rice paper from her brother, my uncle, because he's also a calligrapher. I'm half Chinese, so to me it becomes an element that I can add into this layering of mistranslation. All these things that have meaning become very aesthetic components or material components—they lose their meaning. I'm interested in the erasure of meaning, or the accumulation of meaning through a layering system.

CSHow do you use text in a slightly more deliberate manner in some of your works?

MESThere are works that I do that are specifically about writing, such as the small torso pieces. I take two key words, like the words two and one, and it can be really dumb, like the idea of two lovers and separation, and the idea of a two-state solution, or one country two systems, and I just mutate across different ideas from the idea of two and one, that's like trying to turn a word into plastic material again. I like the idea that it can raise into absurdity, like if you say elbow a hundred times it sounds really strange. It becomes phonetic, so it becomes material again, and then you put it back in a context.

CSOne of the things I was curious about was your interest in logos.

MESLogos contain a magic that's used for commercial purposes. The magic is how you can take something so simple and imbue it with meaning through association—like the Nike tick, and this idea of branding, which is something that's reappropriated from Greek mythology, and Nike the goddess of victory. I'm interested in how a font can change the feel of the branding. I was looking at the most popular fonts for 2019, and a lot of them were fonts for galleries—it's all sans serif, this year. Logos have a magical quality that can be likened to witchcraft.

CSThinking about the multiple references you draw into your work and the title of the your recent show at Chisenhale Gallery, Cite Your Sources, could you talk about how citing your sources relates to your practice?

MESOn the title for my London show Cite Your Sources, I liked it because it's a kind of writer's injunction—there's this kind of necessity to be correct and show an ethical practice in where your thinking or sources come from, and I was thinking for an artist it's very similar, but in a different way. You have to say what you're doing—what you are and what context you're coming from, and that gives a legitimacy to your practice. And I was thinking, what if you don't have a context? What if your context is forcibly removed, or you're not a subject of a system? I'm thinking about my father again, who is Palestinian. If your context is forcibly removed from you, what do you have? I know you have a body—the body is centred in the work, everything relates to some kind of bodily relation or the bridge that you can disseminate the meaning from, whether that's felt in the installation space, or if it's to do with words written on the body, an inscription.

CSHow does this relate to the fact that you started by studying painting—how has your practice developed over the years?

MESWhen I studied painting at art school, it just proved to me that it was not a viable art form or occupation, because it was so conservative, and all the disciplines were separated. It was not very critical. But actually that absence of criticality in my education really helped form the practice.

I always thought that it was unfair that I'm a painter because musicians have the highest control over the affect.

At the time, I was doing a lot of care work and social work with young people with learning difficulties. I thought it would make more sense for me to support vulnerable bodies, and I think the negation or the kind of space it gave me to see that it was not making sense for me, actually allowed me to return to it. It's really hard to work in those industries—like social care, social work. You're underpaid by the government, and then in the U.K., the progress you make with someone—if they have language difficulties, for example—can go backwards if it's not maintained. It made me quite depressed. I was also thinking that this is kind of my raison d'être—thinking about the body and this thing that needs to acquire an integrity. So after a very anxious period in my life, I was kind of forced to make work again. It was after an absence of thinking about art that I could go to it through an urgency.

In that sense, I guess art education was not formative, but negative. I remember enrolling myself in these short courses at university in the critical theory department, and I needed both to get me excited, because there were no questions asked in the painting department. This whole question of interrogating not just of the history of painting but also why—why is it even relevant and why are these people doing this? What are the visual cultures and how do these translate a kind of urgency or state of being, here, now? This was very academic, too, very entrenched in language and citing your sources, all these kinds of correct ways of doing things; so I saw it as a kind of thinking and writing process—raw material.

CSThe body shows up in really different ways in your work, in terms of scale and more figuratively in some of the works.

MESIt's interesting because the register of figuration in an image is very different to the feeling of texture, so I'm interested in that kind of spectrum. The images that you scroll through on Instagram are a different kind of construction to the affect that we feel in a room with a certain smell. Meaning is different and more conscious or constructed in different modes. I always thought that it was unfair that I'm a painter because musicians have the highest control over the affect. So music, film, then art, then fashion—that's the kind of spectrum. Art is more of a conscious realm of construction and meaning, and it's intercepted with all of these conversations about identity and political protest, whereas if it's music, it can just be about the feeling of pain; it can just be about love, without any of that. Film can do both.

CSDo you want to also speak a little bit more about the body and your interest in the body and how you study it?

MESFor me it's always the body as an affect and this idea of pervasive anxiety—the idea of anxiety being lots of fragments that you can't make sense of, that your body disperses into different parts and you can only make sense it of when you give it meaning, which might be a lie. Visually, there's this idea that there's a consequence of the flesh—we all have bodies, regardless of our context, political leanings, and time contingencies.

There's this piece I really like by Richard Serra, titled Verb List (1967–1968). It's a list of things, of all the different ways that you can treat paper—to cut, to fold, to bend, to rip, to tear, to roll. I thought about how all of these things—if you stop thinking about paper, can be applied to the flesh. In a way, you can have a bodily empathy with that, if you translate it to the flesh, and we all have flesh. I do a lot of life drawing with the dead, or I try to get access to the dead, and there's something that happens in the realm of seeing when you apprehend a body very close up. You think you understand it, and you can see so much, but there's a kind of blank in your recognition, because you relate to it so much that you lose a sense of self. I remember doing this trip to Antwerp, and thinking, 'I can do this!' I didn't think it would be weird; it was the first time I did it. Then I saw a woman's arm with liver spots all over it, and it suddenly made me feel something, and I thought, 'Oh, I don't want to do this anymore.'

Seeing and reading are very different things. Reading the news is very different to looking at something, but they're kind of related to absorbing information—different registers of seeing and absorbing different things.

CSThis came out when we were talking the other day—this idea of operating across spectrums, rather than binaries. This happens a lot in your practice, in relation to the legibility of certain texts, the spectrum of figuration to abstraction, all of these slippages are happening. I guess one of the things that's really interesting about your work is this idea of an open-ended question.

MESYes, I think that's really important to preserve, because we're in this place of identity politics and saying what you are, so where do you go forward from that? It becomes reactionary. There's this phrase, productive ambiguity, which is a psychoanalytical term, and words can do this; words can play and mutate. A lot of art that I see has this ambiguity inherent to it, it's not just saying something. There's this space that is still in flux and it can go another way. It's interesting for me how language does that, and how rubber can do that, for example—it's not just statements.

CSWhen you have a finished work, how do you create that sense of ambiguity for yourself?

MESI don't know what I'm doing while I'm doing it. I have a certain idea but it's always a surprise as to how it turns out. You have to have a fixedness when you install it in the show, but the questions that are left in it will span on in the next show, or the next experiment. I think I would just stop making stuff if I knew what I was doing.

CSOne of the things I wanted to ask about was this idea of post-memory and how that works within your practice. Could you talk about how the concept feeds into your work?

MESI have a very close friend who's doing a programme of shows based on transgenerational trauma, and I was quite averse to doing something like that, because the practice would be shut down by the fact that I'm half Chinese and half Palestinian, and then everything is read through that, especially in this moment in visual culture. But, it's very present in how I think and make work.

There is a kind of weight from generations—that you haven't experienced events directly, but that experience is something that's inherited, and you have to work through it. It's almost like a blank, but you feel it as a force that you have to deal with and language is not enough, so it's what you deal with through other materials. Having a Palestinian father, and only going to Palestine a few times and not speaking Arabic, doesn't mean I'm not aligned, it just means I have a different relationship and I feel there is a pull to answer what that means. I'm just trying to figure it out.—[O]