Mike Nelson on Extinction and the Debris of Modern Life

Mike Nelson. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery. Photo: Arnaud Mbaki.

Mike Nelson. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery. Photo: Arnaud Mbaki.

Mike Nelson's first major survey canvases 30 years of the British sculptor's practice, which is no mean feat given that most of Nelson's key works are large-scale site-specific installations.

Twice nominated for the Turner Prize, Nelson is renowned for his work with found objects from past eras, and for his interest in transposing concepts from science fiction into immersive sculptural environments.

Leaping off from the stark proposition of its title, Extinction Beckons (22 February–7 May 2023) engages non-linear models of time—re-staging past works, but also re-imagining them anew.

Presented at London's Hayward Gallery, many of Nelson's installations are shown for the first time since their initial exhibition, including the multi-room labyrinth The Deliverance and The Patience (2001), originally conceived inside a large disused brewery at the 2001 Venice Biennale.

Past the entrance of a small wooden house, visitors make their way through sweatshops and workshops, travel agencies and gambling dens, selecting between the two or three doors that lead to the next space. The installation references the story of the wreck of the Sea Venture in the 17th century and the two ships—The Deliverance and The Patience—that were built to take the survivors on from Bermuda to Virginia.

Reflecting on his installations, most conceived prior to the prominence of digital media and experiential artworks across public and private institutions, Nelson notes in the following conversation that the impact of working on such a scale now is undermined by the commodification of the 'immersive'.

'In many ways, this show reflects my thoughts on the structure of time in which we now exist,' the artist explains. Taken from a motorbike helmet sticker, the phrase Extinction Beckons references the inevitable dulling of human intuition as digital mediums introduce new perceptions of time and space.

Already, the architectural installation The Coral Reef (2000), which earned Nelson his first Turner Prize nomination in 2001, articulated the distortions of modern belief systems. Disoriented visitors wandered the artist's Borgesian maze across 15 interconnected rooms, noting duplicate entrances and exits. With no clear trajectory, they follow one another: a security surveillance office, a mechanic's garage, a drug den.

Scattered throughout, found objects hinted at the identities of former occupants. Retrieved from junk shops and scrap yards, the objects aggregate the residues of a post-industrial age and together stage environments that reveal the processes through which they become obsolete.

At the 54th Venice Biennale, Nelson explored ideas of duplication and replication at the British Pavilion with I, IMPOSTER (2011), which recreated an immersive environment reminiscent of, and referencing, a work originally made for the 2003 Istanbul Biennial. I, IMPOSTER was constructed within the Giardini, using components that emulated—and were actually from—the 17th-century building in which it was originally installed.

As with MAGAZIN, Büyük Valide Han in Istanbul, for which Nelson converted two rooms into a photographic darkroom amongst the crumbling architecture of a 17th-century caravanserai, I, IMPOSTER, a three-month-long construction project, transformed the neo-classical Pavilion into an environment that sat between cultures, geographies, and times.

At the Hayward Gallery, both works have been re-created; the first in its components, the latter under the dunes of Triple Bluff Canyon (2004). Sinister red lights illuminate a domed room, where individual photographs are suspended from the ceiling, overlooking a workbench.

What follows are the makeshift courtyard sculptures from The Asset Strippers (2019), which transformed the Duveen Galleries at Tate Britain—the first purpose-built sculpture gallery in England—into a warehouse of post-war detritus from industry, agriculture, and governmental infrastructure. From their elevated positions, knitting machines and army barrack woodwork commemorate a lost era in Britain while casting a sceptical eye over such methods of display.

Nelson is no stranger to large-scale exhibitions, having shown at the 2002 Sydney Biennial, the 2003 Istanbul Biennial, and the 2004 São Paulo Biennale. His survey at the Hayward Gallery nonetheless features his largest aggregation of objects and spaces to date, spanning 30 years of recurrences in motifs and language, while connecting old works to present concerns.

In this conversation, the artist introduces the exhibition, revisits previous installations, and notes the perceptual distortions that mark the present and future. Where sculpture and stillness give way to scatter and immersion, Nelson appears self-aware: 'the future of my work is unclear, if it has one.'

HHThis is your first survey exhibition. What new threads have you sensed, if any, looking back on your practice over the last several decades? Did you get any surprises?

MLIt was unnerving to find myself inside The Deliverance and The Patience again. While I knew I was building another version, it still took me by surprise. The work is simple in many ways—the carpentry, building work, and collection of fittings, furnishings, and objects are relatively mundane—yet the sum of its parts is far greater.

I stopped working this way after the British Pavilion at the Venice Biennale; I felt the impact and success of such works had been undermined by the commodification of such a way of working by anything described as immersive—theatre, restaurants, cinema, shops.

However, my encounter with this work reinstated my belief that you can sense the intent in something. The work still succeeded on its own terms having circumnavigated a period of exploitation of its own aesthetic.

HHHow did you and curators Yung Ma and Katie Guggenheim decide what to include in the survey? Did you intend to draw out key themes in your work or give a sense of the diversity of your practice?

MLI think I'm a very particular artist to work with and Katie and Yung had to get used to my idiosyncrasies. One thing to understand is that you don't curate me as such—it's more of a conversation that develops with the idea and physicality of the work.

In terms of my choice of works, I opted to be pragmatic both in a practical sense—what existed and could be built within the four-week time frame onsite—and what made sense economically and environmentally in terms of transport.

I chose to show works that are not owned by collections; fortunately, I'm unfortunate enough not to be overly collected. This allowed me the freedom that I would not have had the works been lent. It also lessened the costs substantially regarding transport, installation, conservation, and insurance, which is where most of the money goes in these retrospectives.

I was keen to make an exhibition with distinct chapters, as it were; the effect, or affect, would be a blanket one to some degree. I had suggested one huge Studio Apparatus: the most logical route, which met some resistance. But in the end, you could see the final exhibition as a Studio Apparatus built by me, with the help of the Amnesiacs perhaps.

I was conscious to highlight some of the concerns I had over the past 30 years and their recurrences in motifs or language. It felt important to touch on migration and the plight of people looking for better lives with The Deliverance and The Patience. Its new imagining is almost like a barge or floating island, evoking the earlier work Taylor (1994).

The exhibition's opening wrong-footed you with a familiar trope of my output and life: storage. Yung and I were both keen on this beginning. I was particularly interested in storage because it drew into question the status of sculpture in relation to the matter it's made from.

In this first room, we have I, IMPOSTER from the Pavilion in Venice, but in its components. The red light from the original windows homogenises the space, referring to previous works like Agent Dickson at the Red Star Hotel (1995) and MAGAZIN, Büyük Valide Han. Later, the darkroom bathed in red light migrates under the dune-laden woodshed from Triple Bluff Canyon.

In many ways, this show reflects my thoughts on the structure of time in which we exist.

The Smithson rebuild of the woodshed not only functions as a re-politicising of a seminal work as if displaced by a mirror's reflection—Vietnam and Cambodia substituted for the Iraq war from its inception in 2003—but the inclusion of M25 (2023) and the spiral corridor from After Kerouac (2006), a desert reference, is more indicative of a failing world eco-structure in the face of human exploitation.

The Asset Strippers was made for the Duveen Galleries of Tate Britain, a near-fascist piece of classicism that aped the colonial aspirations of other grand exhibition halls in London. To move the sculptures to a post-war piece of brutalism associated with secular hope is a good context to re-imagine them; however, I was concerned as to whether they would work formally.

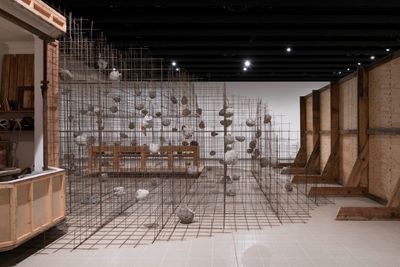

The Studio Apparatus work seemed important to include—and this incarnation, originally made for Kunsthalle Münster in 2014, seemed both apt in terms of its materiality and open enough to contain and work with other pieces that could be re-imagined with it.

One, the projection room from Triple Bluff Canyon—a reconstruction of my old studio from 2003, with the projection of a conspiracy theorist coming from within but projected onto a huge screen spilling over to exaggerate his monstrosity—seemed an important inclusion.

It talked not only of something from 20 years ago that would become mainstream with all the darkness it possessed but of the rapid change that happened over two decades. I bought the conspiracy theorist's lecture on VHS at a flea market. You would have had to access such materials through a PO box in the suburbs of some Californian town.

I used to travel to markets and yards looking for material. Then, I realised you were best off standing still and letting the matter come to you.

The internet has disseminated this material to every corner of the globe, making it a real threat and aggravating the rise of the far right. This, I see as the greatest failure of the left in recent years—a failure to capture the imagination of the people, and the worrying success of the right.

HHYou mention the reconstruction of your old South London studio in 2003, which you restaged for the 2009 Tate Triennial. How has your relationship with the site of the studio changed over time?

MLI suppose the difference now is that I do have a studio, albeit just an old shop space—nothing big enough to fabricate works of this scale. I think re-encountering this room made me aware that I haven't changed a great deal. My studio now does not look very different and if I were to consolidate my storage, it would just look like a salvage yard—which is quite appealing.

To be surrounded by interesting matter of which you are one element is exciting. Especially when you are the only thing that can articulate these things. I used to travel to markets and yards looking for material. Then, I realised you were best off standing still and letting the matter come to you. Maybe this is an analogy to where I am now.

HHTraditional surveys often chart a career as a linear narrative through time. Given your interest in science fiction, what kind of model of time is registered in this exhibition?

MLI once described my process as akin to a threshing machine—moving slowly along a field, turning over, and resorting. In many ways, this show reflects my thoughts on the structure of time in which we exist.

It seems to me that the acceleration of our reliance on the internet has forced us into a new era of digital time—a flattening of time in which things exist almost on a plane, without a linear trajectory. I think this is confusing for us as we are still organic matter ruled by linear time. In some ways, it's creating a disjuncture.

Extinction Beckons is a title taken from a sticker on an old motorbike helmet—dark humour about the pathetic protection the fibreglass shell offers. In many ways, the title functions like Roadside Picnic, Arkady and Boris Strugatsky's 1971 novel; the visitation within that text means everything and nothing, as sculpture returns to matter and back to sculpture. Likewise, Extinction Beckons is both portentous but also flippant; the future of my work is unclear if it has one.

HHThe fictional motorcycle gang the Amnesiacs is a significant aspect of the exhibition. Its meaning changed for you over time—from a means to forget aspects of what you were taught at art school to a mechanism to grieve the loss of your friend Erlend Williamson.

What do the Amnesiacs mean to you now? How are they represented in this survey?

MLThe Amnesiacs are a constant presence in the imagining of the work as a whole—their ethos or methodology is never far away. Their physical manifestation is contained within a chicken coop hidden at the back of the lower screen in Gallery 3. Within are remnants of their early manifestations from 1997, with later editions within the same language.

I had hoped to include the motorbike helmet from which the title is taken—almost a 'Rosebud' moment from Citizen Kane [1941], where the title's importance and/or lack of importance would be realised. Unfortunately, due to budget constraints, this was not possible.

Ultimately, the cannoning of time in one's own life, mirrored by a world deep in change that potentially renders human time and memory redundant, will offer further chapters for new incarnations of the Amnesiacs. —[O]