Gala Porras-Kim: The Afterlives of Museum Objects

In Partnership with Gasworks

Gala Porras-Kim. Courtesy the artist and Gasworks.

Gala Porras-Kim. Courtesy the artist and Gasworks.

Colombian-born Los Angeles-based artist Gala Porras-Kim's work addresses the frameworks of cultural heritage, prompting viewers to become more aware of individual histories and spiritual practices beyond museum label notations.

The artist investigates the evolution of objects throughout time, working with archaeological and ethnographic collections around the world to inquire into the ethics of conservation, cultural heritage, and the plausibility of an all-encompassing 'encyclopaedic' knowledge.

These include objects, artefacts, and human remains from renowned institutions like the British Museum, often obtained from non-Western countries during colonial times.

Porras-Kim's recent exhibition at Gasworks in London, Out of an instance of expiration comes a perennial showing (27 January–27 March 2022), re-imagines artefacts from the British Museum's funerary art collection from ancient Egypt and Nubia. Porras-Kim spent time in the British Museum during spring 2021 as result of a partnership between Gasworks and the Delfina Foundation, speaking to staff members and curators about alternative ways of conceptualising the institutional afterlives of ceremonial objects and human remains.

Proposing new ways to make sense of the material and spiritual conditions of artefacts stored in archaeological collections worldwide, large-scale drawings, sculptures, and sound work responding to objects in the British Museum's collection were presented alongside letters to the museum's staff, questioning policies concerning the conservation of human remains.

Among them, the replica of a 4,500-year-old sarcophagus from Giza has been rotated to face the sunrise east, following ancient Egyptian customs, while the paper marbling work A terminal escape from the place that binds us (2021) employs ink divination to ask spirits inhabiting a set of human bones from the Gwangju Museum collection where they would like to be buried.

The latter work was shown at the 2021 Gwangju Biennale, attesting to Porras-Kim's site-specific practice, which responds to museum collections where the initial research takes place, from the Gwangju Museum of Art to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

In this edited transcript of a talk that originally took place at Gasworks, Porras-Kim speaks with curator Sabel Gavaldon about her time at the British Museum, spiritual beliefs in ancient Egypt, living matter, and alternatives to museum deaccession.

SGThe British Museum is the blueprint of every encyclopaedic collection. If you think of universalist institutions born from Western modernity with the mission of embracing and incorporating all aspects of human culture—well, this is where it all started.

To open this conversation, could you tell us more about your experience researching the British Museum collections during your Delfina residency last year?

GPKI have been looking at artefacts in collections, including the subcategory of things that were never supposed to expire. After working with collections elsewhere, I wanted to come and see how the British Museum works. I thought it would be the most conservative and the hardest one to deal with because it's so old and so big.

I thought as a working practice, if I could have the same conversations I had with other museums, it would be like meeting the boss!

I've been to the museum before, a long time ago, but after the work I did at the Delfina Foundation, inevitably, the work ended up being about Egypt. Egyptians planned for the afterlife really well, as ancient cultures planned to exist indefinitely, and in a sense, they do.

SGIn the past, you've spent so much time researching how Mesoamerican art is conserved and displayed within collections in the U.S.—that's something that has become quite intimate to your practice and even your identity as an artist.

However, here in London, your focus gravitated towards a different cultural heritage, as you've been responding to the Ancient Egypt and Nubia departments at the British Museum.

GPKMy previous work has been about Mesoamerica, but that's circumstantial. I live in L.A. and go to Mexico a lot. Many museums work similarly to each other, so it's not so much about where the object comes from.

Museums tend to follow the same type of regulations, display, and concerns about how to care for the material elements of works over other things they could consider. Objects might have a function that is more important than their material being.

SGSince we're talking about collections, I think it's important to highlight how your work often results from collaboration and partnership with academics and institutions.

Last year, you were a research fellow at the Radcliffe Institute at Harvard, you've been in residency at the Getty, and you've also produced artworks in dialogue with curators, conservators, registrars and all kinds of researchers, from international copyright law experts to quantum physicists.

However, you always make it clear that your position is that of an outsider—that you are not an expert.

GPKI'm not an expert at all. That's why I have to work with them. I am not an expert in the subject but it's something very simple to see.

You read the institution's mission statement and see how people want to deal with the things they are caring for, and of course, practical things about current life always get in the way. Many people in museums have inherited methodologies—from the 1960s, 70s, or even the 1800s—that they might not be so inclined to follow now, but are in the regulation and day-to-day workings of the institution; there isn't much space in their day-to-day job to account for old ways of working.

SGMethodologies are important here. Your work often contains letters and follows a paper trail of conservation reports, email correspondences, museum inventories—aspects that involve institutional policy.

You are dealing with issues that are so niche and specific to a certain research field, but you're taking the position of an outsider who looks at these matters with a fresh pair of eyes. You're reading things literally, at face value.

I'd like to think this also applies more generally to the figure of the artist who comes in with an eccentric perspective. They can see elements in these documents that are not obvious to those who are involved.

GPKMost of these projects stemmed from my personal anxiety about history and not knowing what it's like for objects to be part of the default of an institution. The first time one of my works went into a collection, it was so difficult to fill out the questionnaire.

The museum questionnaire asks: what are the specs of this work? The conservation process? The dimensions? There is no way I can plan or know how something will be cared for in 200 years. Ten years from now? Maybe.

I think, with these questions regarding contemporary works, we can see how these methods might apply to things that are way older. I feel like when I collaborate it's cheating, in a way, to browse through the people who are inside an institution's brain all the time.

People working in institutions already know what the issues of museums are, for the most part. I get all kinds of coffee conversations that are like, 'Let me tell you all the problems of the museum,' because people already know.

You read the institution's mission statement and see how people want to deal with the things they are caring for—and of course, practical things about current life always get in the way.

SGSo much of your work involves materials and processes that are fungible, malleable, and ephemeral—a lot of it changes, decays, and eventually disappears.

I wonder to what extent your questioning of museum conservation responds to a more 'selfish' interest, as an artist whose practice is concerned with time, permanence, and cultural transmission?

GPKI am trying to multitask! Regarding what you said about the policy, the paperwork, and the day-to-day steps of the museum, that is also seeing the background skeletons of how people care for old things.

You see it in the front end; you see the display and the little card, and it says what the thing was supposed to do, but looking through the conservation reports or accession record, it's the way the objects actually exist today in the deep vault.

So I am more interested in the niche subsection of objects that were never meant to stop doing something. Like a perpetual function. It would still, in theory, be doing, and then also as a work in a museum—it's a history thing. People talk about it in the past, but those two functions exist in the same object.

SGIt's interesting you use the word 'care', which has become increasingly important amid urgent debates about cultural restitution, deaccession policies, and so forth. But from a practical standpoint, it's unlikely that most of the objects from a collection like the British Museum's will be deaccessioned anytime soon.

As you were saying after your time in the collections, if these objects are going to be there for a while, let's at least make sure we are asking the right questions about what it means to care for an object in this context.

It's not just about caring for an object's physical dimensions through conservation; it's also about its immaterial, emotional, and spiritual dimensions, taking into account what those objects meant for the cultures that produced them.

GPKIt's an exercise to see the materials and who has stakes in that specific space. The ancient Egyptians might not still be around in the form we think, but they had planned to be there indefinitely like that Nenkheftka sculpture, for example.

The granite sculpture was one of the 12 objects that Nenkheftka was supposed to be reincarnated into and one of the works from the museum I was interested in, but seeing what it would be like if what he wanted to happen actually did.

When we were looking for people to talk with at the British Museum, we found a bioarchaeologist who cared for biological things in the museum, like mummies. In ancient Egypt, the reality was that you could come back as granite—then does granite become part of biology because it is now holding a person?

SGJust to be clear, the Nenkheftka sculpture statue was a vessel for this person's soul.

GPKIt was a new container for his soul; we don't know how but it was the afterlife for them. So let's consider what 'biology' might be when we include this sculpture as containing life. All that information about him being reincarnated into granite is on the label already and part of what I did on my first trip here was to look at the labels that had to do with objects that might still be doing something from the past.

The label says Nenkheftka was supposed to come back inside this thing. Let's literally do what the label says and see if there's a person inside the sculpture. This work is made with the dimensions of the vitrine that is around the object now—this drawing is to be wrapped around the vitrine so he can have a better view.

This drawing is a picture of a landscape that is currently a UNESCO park—a whale cemetery. At the time he was alive, he might have gone there to see it. The image is a placeholder for the idea that he might want to look at something else. It's very speculative, in a way, but I want people who are caring for the object to see it the way Nenkheftka did and what it would be like to consider ancient audiences that might be in the museum.

SGSo you're offering to the museum Sights beyond the grave (2022) to be used for that purpose?

GPKSights beyond the grave includes a letter to the British Museum understanding that it could be overwhelming to have all these peoples' needs for an afterlife being expressed suddenly because they do have a lot of specific directions about how they wanted to be living onwards.

Some of what the museum is doing already parallels what the ancient Egyptians wanted, which is to preserve their physical body. Through museum conservation, they are being well preserved.

SGWorks like this come from reading things in the most literal way possible. In many of your works, there seems to be a sense of suspicion against the traps of metaphorical language.

You are saying to the museum: 'If Nenkheftka's sculpture is a vessel for his spirit, then let's take this at face value and pay tribute to this object as the person it is. Let's deal with it as "somebody" rather than "something".'

Maybe we can link this to your largest commission for your exhibition at Gasworks, Sunrise for 5th-Dynasty Sarcophagus from Giza at the British Museum (2022).

GPKThis is a 5th-dynasty sarcophagus in the British Museum; it is facing south-west, but the label says ancient Egyptians had fake doors facing east, so that the dead can have a vision of the living and the sunrise.

The proposal is for the museum to rotate the sarcophagus so that it is facing east. It doesn't stop being on view and acts the same way, but by repositioning it, it can return to facing the direction it was originally intended for, since that was important for someone. It's like curating two shows at the same time; one for people who are alive today and visit the museum regularly, the other for ancient living audiences that might actually care.

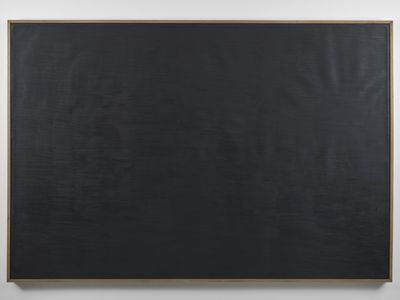

The Mastaba is the place where these sarcophaguses were buried. I have been making a series of these works that are landscapes—things that we, as living beings, might not be able to see yet because they are either inside a pyramid or a grave, where light doesn't enter, but they are really for another type of vision and audiences.

SGGoing back to what we were saying earlier, collections like the British Museum's are Enlightenment-era institutions that were supposed to display the entirety of human culture, so that everything is visible and transparent to modern eyes.

Many of your works point to what is occluded from our vision. In some cases, you're pointing to realities they were never meant for our eyes to see, I'm now thinking of your Mastaba scene (2022).

GPKYou will be able to see it when you are dead! That's the line I like to follow. Museums that show historical works feel so scientific, and they can be. They feel very factual but I like to live in the five percent of uncertainty. What if things actually work the way people in the past believed? Give this type of knowledge a chance to be prioritised over what institutions might know today.

SGMaybe we could make another link here between your Mastaba scene and the replica of the Giza sarcophagus, both of which point to what one cannot see.

The sarcophagus replica raises an important philosophical question, which affects but extends beyond the ethics of museum conservation—at what point does a human remain become a cultural artefact?

What does it take for 'someone' to become 'something'? And more importantly, how can we restitute the personhood of an object?

GPKI wanted to make a work about Luzia, the oldest mummy in the Americas, now housed at The National Museum of Rio, which caught on fire. While I was researching, I talked to the national coroner of Brazil who gave me a five-hour lecture on the history of how policy has been updated to define what death is.

I am interested in the regulation that says when a body or a dead person becomes old enough to become an object, history, or a relic. He went through the history of when that was. In the day-to-day, death is defined by the law and by institutions.

I went to the Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo in Sevilla, which had been a monastery and has a tomb with people inside. It's how things are catalogued—if it's in a museum, it becomes a museum object, like art. If works like that get accessioned and catalogued, they become objects. It works the other way, too—if a dead person enters your collection, the building becomes a cemetery.

For Luzia—we had no idea what this person was called—I thought about the different ways things can be deaccessioned, which is rarely spoken about, and when it is, it's bad, for the most part. Part of Luzia lived through the fire, while 20 percent of her body got burned.

It was intense, the fire burned so many things. I read in the news that they tried to put the other 80 percent back together. If you think about the fire as a supernatural event, somebody was able to partially escape the museum because there is no deaccession policy.

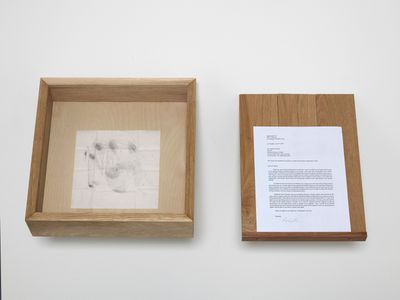

SGThis relates to another one of your works, which is a hand imprint made with ashes you found among the rubble at the Museu Nacional in Rio de Janeiro, produced after the devastating fire that consumed its entire collections in 2018.

The title of this work poses a question to audiences—is leaving the institution through cremation easier than through deaccession policy? What does it take to escape the museum? It comes with a letter about the fire. This is the way a body can literally escape the collection.

We have a question from the live feed: 'If a positive change could be to include the hidden peoples or spirits as well as the objects themselves in the museum's mission, how hopeful are you for a change in that direction given all the museum folk you've been in contact with?'

GPKI am very hopeful. Considering how old and slow the museum is and the rate at which things have changed recently, the fact that people are willing to have a discussion with me gives me hope.

I know that in the U.S., there are institutions that are really trying to think about that subcategory in their collections, and some have specific times people can come in and perform a ceremony and literally turn the building into a cemetery for a couple of hours.

The best one I've heard of so far is that there is a maize god in a museum, one that needs to be fed. There is a curator there whose job is to feed it corn occasionally. This is the moment the museum does something that goes against their conservation brain. Corn has acid! Destroying day-to-day function of objects because you are literally putting acid on the object, but you also know that by doing that you are making it live.

With technology, everything that has ever been made by a human can be found in our lifetime. Why should we keep so many of these things? These are ways to experience these objects in a way that compromises with the past.

I'm not saying, let's put everything back and repatriate. I don't know what the solution to that is, but in day-to-day workings, there can be small changes, especially if they are symbolic. So many of these things can be symbolic for someone who might come back.

I am more interested in the niche subsection of objects that were never meant to stop doing something.

I have been thinking about a proposal for the policy of specific objects. Instead of physically moving it, you change the ownership of the object in the museum's forms. The owner isn't there to care for it anymore, but say we change it from 'owned by the British Museum' to 'owned by Nenkheftka', he owns his own sculpture and we are caring for it indefinitely.

SGThe museum becomes a steward.

GPKYes, it's not owned anymore. How do you own the vessel of a body?

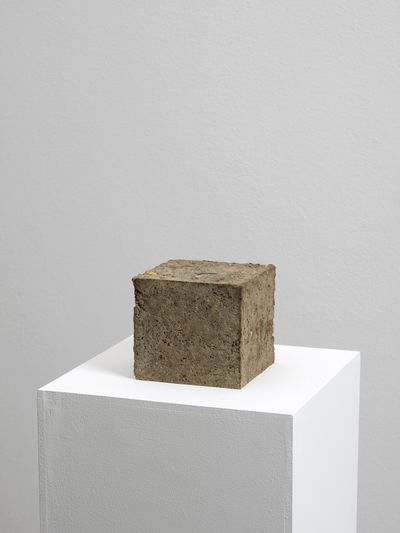

SGThis connects to the cube sculpture—The Michael C. Rockefeller Wing at the Met 1982–2021 fragment (2022). It's the smallest object in your show at Gasworks, but so powerful and in many ways, the elephant in the room. What is the material constitution of this object, and what does it entail?

GPKThis is a work I just made. I didn't know it would take this shape; maybe I am still thinking it through.

SGYou arrived at Gasworks with a hoover bag to make it!

GPKIt's a cube made of remnants! It's made of the stuff collected in a vacuum cleaner after the Ancient America, Africa, Oceania room at the Met was de-installed for the first time. The Met is re-installing the Rockefeller Wing, which has never been re-hung. They opened the cases and moved things around, and the dust and detritus around the objects mixed with the people who had seen the objects between 1982 and 2021.

Someone vacuumed and I collected them; they are a fragment of a specific period.

SGLike a time capsule.

GPKLike a fragment of time in which those objects were seen by those people. It won't happen again because it won't be hung the same way. I thought it was a fragment of a moment.

SGUp close, you can see hairs, sediments... Who knows what these are! Maybe this notion of residue points to another important aspect of your show at Gasworks: the idea of things that are alive in a museum's collections.

It's not just about organic matter, fungi, and microorganisms, but also the spirits contained within objects and human remains. These are like stowaways in the museum. They are there even if the museum doesn't want them to be!

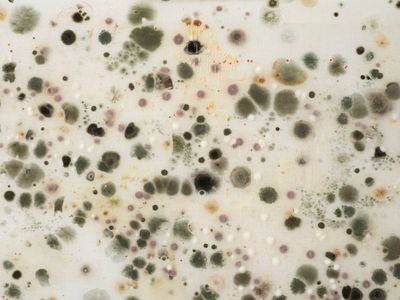

GPKMould extraction (2022) is very much linked to Luzia. It follows a similar idea of how things can leave the museum. From talking to the people there, one of the main concerns in conservation is mould and decay. I thought a way for objects to leave the museum could be through the stomach of a spore or a type of mould, if they have stomachs.

What is the biological function of consuming an object and then leaving with it? You went and collected spores from the British Museum storage for me and I talked with a biologist friend to figure out how to propagate them.

In the work, it's deaccession through the spores. At some point, they ate objects in the collection and we are regrowing them in the space.

SGThis work changed quickly over the duration of the exhibition, and then disappeared.

When you started the work, it looked almost like a religious relic. It had a certain aura as a time capsule in the form of a blank sheet with a few spots of dust and traces. As the mould grew, it became a vibrant, colourful drawing, one made with living matter that somehow draws itself.

GPKMy practice is a lot of very heavily rendered drawings. I have been trying to figure out different ways to make these images more efficiently, so the spores are like assistants and they are making the images.

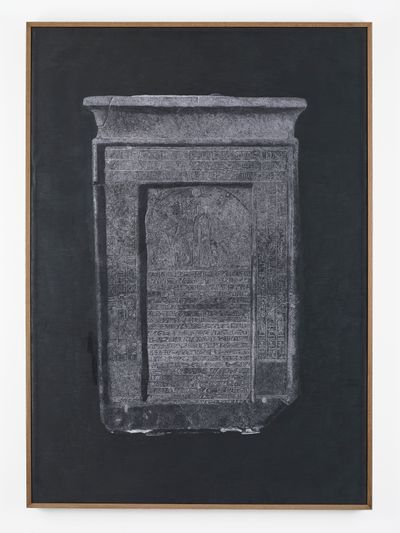

SGWe need to talk about Out of an instance of expiration comes a perennial showing (2022), one of the largest commissions in the exhibition. It responds to the stela of Hor and Suty at the British Museum, and includes a drawing and a sound work.

Can you tell us about it?

GPKWhen I was looking at the things in the museum, the stela was at the front entrance in the dead-people room section. I thought it was great. It was an introduction; here, we can enter the afterlife. I read about it, and it's actually a song. I thought it was unfortunate as an object, a bit like a mummy too. We see a shell but we can't access the living part.

SGSo you commissioned music archaeologist and classically trained singer, Heidi Köpp-Junk—who is also an Egyptologist, of course.

GPKThere is no sound, it's a score of something. Heidi made an interpretation of how the sound would be. She has a sense of what ancient Egyptian melodies were like and she knows what it says. In the gallery, this work had a sound component, which is her interpreting it.

SGHeidi brings ancient Egyptian hymns and songs back to life using her own voice and historical replicas of Pharaonic lutes and lyres, among other instruments. She has spent years researching hieroglyphic inscriptions and depictions of music from the era.

She has even figured out the original tuning of some of these instruments, but there are so many elements that are unknown and impossible to retrieve, from the melodies to the exact pronunciation of Ancient Egyptian, which is a convention among scientists based on contemporary Coptic language.

I can't help but see the many similarities between Heidi's methodology and your work. There's research and precise, historically accurate data, which is then used to navigate an ocean of speculation.

GPKYes, she was approaching it as a scholar too—it's a different type of interpretation. There were Zoom conversations in which she was saying, 'This part should be romantic because it is softer,' but I was like, every person's love language is different.

It's about seeing the blend of her way of expressing romantic styles versus anyone else's and the same goes for viewers and ancient objects.

SGWhatever your interpretation, it's fine. It's a conceptual premise.

GPKI'm not saying, let's put everything back and repatriate. I don't know what the solution to that is, but in day-to-day workings, there can be small changes, especially if they are symbolic.

SGWe need to talk about A terminal escape from the place that binds us (2021).

GPKThis is an existing work for the Gwangju Museum. It's one of the works I did with a human body—I wanted to find out where that person would want their remains to be rather than the museum. I don't know the mechanics of the afterlife or how to contact them, but I know there are mediums and processes of art-making that are difficult to control.

In that work, there are other elements like climate or gravity that compose the image. This is a paper marbling—you can see the scale, it's pretty big. It also comes with a letter explaining the process by which we laid ink on a pool of water; the ink was moving and we thought, here is a gap of opportunity where we can produce an image that can't be predetermined.

Maybe this person on the other side can chart a geography of where they would rather be. It doesn't need a result, the idea is to suggest that they might just be.

SGIt's a map that can't be read.

GPKThe purpose of the work is not to find out where they might want to be, as that person may or may not exist and there's so much uncertainty, but to create a gap and suggest there could be something else—beyond the material in a box inside the museum.

SGThe gap between what we know, what we don't know, and what we aren't even thinking about becomes obvious.

GPKIt's about landscapes and visions.