Naeem Mohaiemen on the Afterlife of Care and Memory

In Partnership with Bildmuseet

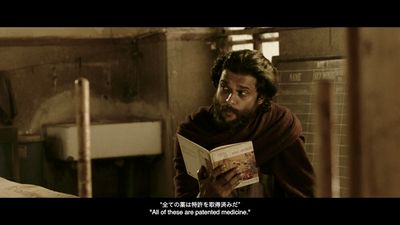

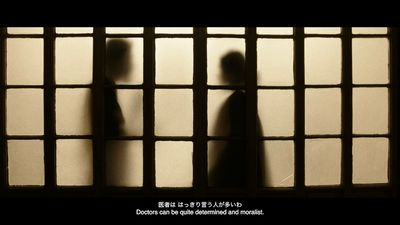

Naeem Mohaiemen's new film Jole Dobe Na (Those Who Do Not Drown) (2020), commissioned by the 2020 Yokohama Triennale and Bildmuseet in Umeå, Sweden, where the work is on view until 15 August 2021 after its debut showing in Japan, is a dreamlike and meditative story about loss and care.

In an abandoned hospital in Kolkata, a man moves through empty wards, running an endless memory loop of the last months of his wife's life. Scripted and filmed before the pandemic, the film focuses on the afterlife of caregivers in the wake of an untimely end.

At Bildmuseet, Jole Dobe Na (Those Who Do Not Drown) is presented with earlier works on memory and history, including the acclaimed film installation Two Meetings and a Funeral (2017). Recently shown as part of the group exhibition Non-Aligned at NTU Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore (4 April–27 September 2020), the three-channel video installation explores the legacies of failed utopias in the context of the Non-Aligned Movement and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, considering the possibilities and pitfalls of the movements that arose from the surge of decolonisation during the Cold War.

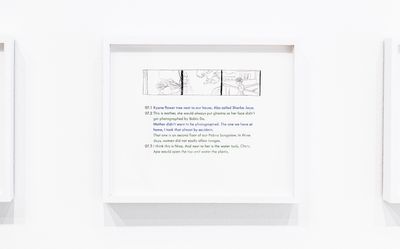

The oldest work at Bildmuseet, I Have Killed (2009), was first shown at Frieze London with Experimenter and comprises a set of photographs that read as a film reel. Based on South Asia's turbulent history of violent change in government, the work questions the accuracy of memory and whether certain events may have been premeditated.

The slippage between appearance and reality is a throughline in Mohaiemen's work, as seen in I Have Killed, which comprises text in the form of a haiku that signals that things may not be what they seem.

In films, installations, drawings, and essays, Mohaiemen investigates utopian legacies in the aftermath of shifting borders, malleable citizenship, and language wars. In this conversation with Katarina Pierre, director of Bildmuseet at Umeå University, held on the occasion of the artist's largest exhibition in Scandinavia to date, Mohaiemen unpacks his most recent film, along with some of the themes running through his work.

KPStarting with Jole Dobe Na (Those Who Do Not Drown), can you tell us why you made this film and why this topic interests you?

NMThe story goes back to conversations I had with several people, including you, even back in 2018, about experiences that I've had, which, of course, many people share. Anyone with aging parents or in relation to someone who is ill faces a point where they might have to question whether more hospital care is what that person needs, or if it would be better for them to come home. The dignity of final days and the path of choosing an end.

The paradox is that your family member might be in hospital precisely because you do not think it is their last days, and you think there is something that science could do. If they could just stay two more weeks, do a few more tests, and be given more medicine, maybe something will happen. I have encountered this situation multiple times, around the question of medical care and whether to continue it or not.

The instigation for the film was an invitation from Raqs Media Collective, who were the curators of the Yokohama Trienniale last year. The three members of Raqs contacted me with a question about whether I would consider exploring the question of care, under the rubric of that Triennale's theme of Afterglow.

That is where the project started and then continued and ended up being a film completed during the pandemic, which was, of course, not something we had planned, but that cast a shadow over the making of the film.

Our relationship to the archive has always been marked by this continuous erasure.

KPWould you say that the pandemic made this into a different film?

NMWell, yes, in a few ways. One is actually quite commonplace, which is that we were halfway through filming in India, in Kolkata, when the lockdown began. In fact, we had finished one round and intended to go back and film the gaps and repetitions.

We were editing and then the lockdown started. And we went into this phase, which I'm sure is common to many people, where we thought that maybe it would be over in one month and we could just wait one month, or two months, or a few more weeks. And then that process never ended.

One specific impact that it had is that there were additional scenes we wanted to film, and in the end, we understood that this wasn't going to be possible. The second thing is that we edited during the lockdown, so we could not be in the same room. We had to work remotely. Even people who were in the same city, in Kolkata, were separated.

The third thing is the film's reception. Although the film was not written with the pandemic in mind, by the time it came out, we were in the middle of the surge. So, the reception changed.

It is an inadvertent irony that when it premiered in Yokohama, people had to wear masks while watching it. Meanwhile, on screen, a fiction about the refusal of medical care unravels—not a resistance to science, but some sort of questioning of the limits of science.

KPIt's amazing that the film speaks straight at us in this current moment with the pandemic. It's asking the questions that we are all busy with. I would also say that the film is truly beautiful.

We follow a couple in their everyday dialogue and routines and their conversation touches on these issues: expectations of medical science, our different belief systems, and funeral rites. At one point, one of the protagonists says: 'Maybe we expected too much of doctors.' May I ask you the same question? Do you think we expect too much from medical science?

NMWell, that dialogue is a reference explicitly to, not only what you are expecting the doctors to solve, but that there is even the expectation that they become your proxy family. That they can answer all questions, including questions around ethics and morality. Conversations that perhaps family members need to have with each other.

It is linked to another dialogue in the film, which is, again, from a personal experience I had, where the narrator says: 'To fall sick is the original sin. If you die, the doctor killed you. If you live, God saved you.'

This dualism is a complex relationship where there is incredible faith placed in doctors, and there is also skepticism if things go wrong, which is related to, I think, suspicion of institutions.

You asked earlier about the pandemic and its impact on the film. That fragment from the film is a strange piece of dialogue to hear now, when we are at the opposite extreme. We are in the situation, myself included, where we are now looking to science and medicine to rapidly resolve the malady of the virus.

KPSomething that struck me, watching the film during the Covid-19 pandemic, is that in some respects, the current moment has brought home, to first world countries, the precariousness and the fragility of human life—a fact that is no news to other parts of the world.

We have discovered that science cannot save us from dying. In a way, I think that the pandemic has changed our approach to death. What would you say?

NMWell, I think I'll add a few more layers. The epidemic has laid bare fragility, but of course, that fragility is highly striated. Certainly in the United States, but not only there. It has revealed the vast discrepancies based on racialised capital as it maps class backgrounds, and that there's a precarity shaped by poverty and access.

It was said about the previous American President that he lost interest in the pandemic when he found out who the majority of the victims were. The disease had a much larger impact on African American, Latinx, working-class communities in the United States. So, the possibility of empathy also went away when he found out who the worst hit victims were.

For new immigrant communities, there is intense precarity; and of course, class above everything else is a defining predictor of your access to health care.

I was reading a news item about the battle that is going on right now around the vaccine's distribution in other countries. In the South Asian context, normally the elite can leave the country when it comes to medical care. It is very common for individuals to go to Singapore, India, Malaysia, or Thailand for treatment. It is a well-defined, revenue-generating category of 'medical tourism'.

Suddenly, because of the nature of the lockdown, people could not leave. The elite had to rely on the same medical system that the rest of the city's middle class routinely navigated. Certain things were made stark in that moment.

My worry is that the lesson will be forgotten when things get back to 'normal'. I think perhaps for some of us, the concern is how can we get to a place where the lessons of this time are implemented, or continue to be implemented, or acted upon when the pandemic is over? That we don't go back to some of our old ways, globally.

KPThe final scene of Jole Dobe Na (Those Who Do Not Drown) is very moving, when the man combs the hair of the woman. Could you share some of the context, references, and details behind it? We don't know the background of the man and woman in the film, for example.

NMSome of the context is not immediately legible to those who don't speak Bengali. Even somebody from another part of India who doesn't speak Bengali might not pick up on some of the references.

One thing that is a little bit buried in the script is the fact that they, as a couple, are of two different faiths. It is never fully explained, but those who understand the language references will know that she is of Muslim origin and he is of Hindu origin. Even here, by adding 'origin', I mean to make vague how practice-bound their relationship to faith may be.

It was inspired by a friend of mine who is in an inter-faith union. One reason it is relevant to the script is the question of what funeral rites will be used. If the partners are of two different faiths, which ritual will be embraced? Or will you not embrace a ritual tied to faith and go for something else, that's more... There's no 'neutral', but a space not marked by faith rituals.

The other thing is that they are not only of different faiths, but he is from a family that moved from present-day Bangladesh to present-day West Bengal, India, during the British Partition of India.

In 1947, his grandparents moved, which is an idea based on the actor's real-life experience. If you came from the other side, the part that is now another country, you actually speak a form of Bengali that has reference points that indicate a time before the Partition, when it was 'undivided' India.

In Kolkata today, it is sometimes a reference point where people comment on the sort of Bengali you are speaking; that you're speaking the Bengali from 'over there'.

The way I am describing it, it might seem like a very small thing—like a difference in an accent, or a few words. But there are oceans of sorrow underneath, because it's the loss of a country that was once yours.

It was the movement that could not be reversed. The Partition of India, as the British left, also resulted in one of the largest movements of people in modern history, from one side to another.

That has been a theme in my earlier work, including works shown here at Bildmuseet. My family has also gone through a variation of this motion. Although my family went through it in the opposite way, which is that they, in some ways, benefited from the Partition, because people left the villages and towns that they lived in. Then there were fewer people, and suddenly there were more opportunities.

The Partition as a historic act has had a different impact on different families. There are those who have lost and those who have gained, and some of that is quietly in the script—never spelled out, but there for the reading.

KPIn this film, like in many of your other films, such as Tripoli Cancelled (2017), architecture has a prominent role. You are filming in these fantastic spaces that you also give some kind of first role to. You almost make the architecture into a protagonist in the film. Can you tell us a bit about the abandoned hospital where the film was shot?

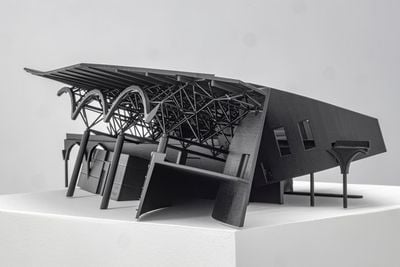

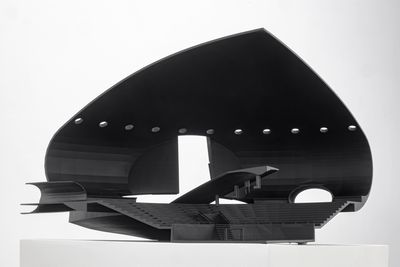

NMThe other film where architecture plays a very large role, which you are also showing, is Two Meetings and a Funeral, with Non-Aligned architecture across three countries. That's probably the film in which the architecture is most explicitly in the foreground.

Jole Dobe Na, filmed in an abandoned hospital, has familial linkage with Tripoli Cancelled, which was filmed in Athens' Ellinikon Airport—a different story, but with similarities about the eroding family unit. Initially we wanted to film in a functioning hospital, because we wanted to give the sense of being lonely within a crowd.

People don't necessarily feel community when in a hospital with everybody else there. In fact, everybody else might be 'in the way' if resources are scarce. Those other 20 people in the waiting room are in an imagined competition for scarce resources, of even being able to get in to see the doctor. It is not a time that can build community. Not always at least.

The slippage between appearance and reality has been a throughline in my work.

It became clear to us that in Kolkata, as in many places, filming in a living hospital was out of the question because of various incidents that happened in the past, and also because of concerns from the hospital itself. Our location manager miraculously found this location when it seemed we were at the end of options. It was a former maternity hospital that closed over ten years ago.

Within a decade, it has taken on the skin of being left behind for many more years. The script changed once we decided to film inside that space. We were no longer trying to create reality. We were in the remnants of what was.

Then the idea changed to imagining that he had already lost his wife. He is haunting the site of her death in his mind, where he keeps going back and reliving that scene.

The story also altered once that architecture came in. It's a building that was not originally designed as a hospital. You can tell from the very high ceilings and the columns. There's also something quite specific about a building used for something else. Now that use is gone, and all the medical equipment is pushed to a corner room for storage.

It already had a character and intent and emotion of its own, and then medical purposes were imposed on top. Now that purpose has left and the building is back to perhaps what it once was. I believe that buildings have emotions and characters and carry their own memory within them. We only picked up a few of them in the making of the film.

KPLet's have a look at the other works included in your exhibition here at Bildmuseet. The new film, Jole Dobe Na (Those Who Do Not Drown), is presented with earlier works—wall-based work, sculptures, installations, and video works—on memory, photography, and history.

For example, Rankin Street (2013) and Baksho Rohoshyo (2019) are based on your family history and deal with the relationship between memory and photography; about the unreliability and fragmentary quality of memory.

Many of the works relate to the violent history of South Asia, from the time of turbulence and uprisings. We also present your acclaimed film installation Two Meetings and a Funeral, which premiered at documenta 14 in 2017. Could you say something about the older works in the show?

NMThe oldest work there is I Have Killed, which is from 2009. Each work looks at an event, or what you could call an inflection point, often marked by catastrophic violence, or at least confrontation between state and individual, or state and movement.

I did not deploy this language back then, but I suppose I was trying to create some sort of parafiction archive, always based on the actual event and giving the audience a slight clue that what is being shown is not a physical document, but a simulacra of the same.

The images here are meant to connote a filmstrip that you're looking at frame by frame, trying to understand what is happening. It's based on the idea of the Zapruder film reel, which was accidental footage taken of John F. Kennedy's assassination in 1963, which is a widely studied forensic object. They studied it frame by frame to try to understand if there was one assassin or more, and whether there was a conspiracy that was larger than an individual.

My images are a fictional recreation, because they are in colour and they were photographed in 2009. There are certain artifacts in the images that didn't exist in the seventies, including shatterproof glass. The text underneath is in a broken sentence form that suggests that things are not what they appear to be. The slippage between appearance and reality has been a throughline in my work.

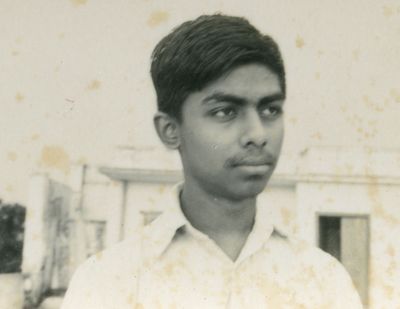

Then there's Rankin Street, and you're showing parts of the project. You're showing the video and also the blueprint drawings, and the stand-alone drawings called Baksho Rohoshyo. Those are all derived from a box of photographs that my father took in 1953.

Part of what marks the project is that my father, although he's been a surgeon his whole life, was an obsessive photographer. He took photographs actively for about 20 years. But nothing was really preserved, because photography is not his profession, medicine is; so nobody in the family thought it was important to preserve all these things, which is also common when families are always moving, and home keeps changing.

Because there were so few images, I kept revisiting the same material and thinking of new ways to work through it. The limits of the material mark the work.

The third project is Two Meetings and a Funeral, which is the three-channel film, shot in 2017. It's about the Non-Aligned Movement, and the intersection and friction between some idea of Socialism outside the Soviet bloc and the idea of Islamism as a unifying ideology across nations in the 1970s.

KPIt seems that you have a particular interest in memory and the fragility of our memories but also how our individual lives and histories are connected to a bigger history. Would you like to say something about that? Why this obsession with memory and with forgetting?

NMWell, everything starts with the self. I have a very poor memory for daily, everyday things. I will forget things that are from a month ago and it will come up in casual conversation. I will say something and the person might say, 'Wait, but we had this conversation just a month ago.'

In terms of functioning in daily life, memory does not serve me well. I have poor recall and I often apologise for it to friends. I think that's where it always starts. If my most immediate memories are so fragile or keep getting erased by whatever is getting put on top, then how fragile must distant memories be?

If people are using memories to settle debates on events that happened in the past, the official records are changing, or are being altered, or being guided based on somebody's fraying memory.

Today we live in a society that is constantly self-documenting. This event that we are doing right here is also on the internet and it might be archived. In some ways, people do not have to rely on memory in the same way. There is documentation all along the path, the digital trail of everything we do. It is one reason why we don't memorise phone numbers anymore. Everything is recorded somewhere.

Generally, in terms of historical debates that run through all nations, I am trying to argue for more ambiguity and less certainty about the way things happen.

The period that I look at, which is the Cold War 1960s and 70s, is a period where documentation is, in many instances, lost. This idea of memory shaping events is very distinctly there, because if my recall of the event is the only record that exists, then my oral history becomes the document. It's relevant to put all of it into question; into discussions of ambiguity.

Generally, in terms of historical debates that run through all nations, I am trying to argue for more ambiguity and less certainty about the way things happen.

KPYou also talk about history and the lack of archives and the lack of documentation, and the lack of the documents... Or the destruction of the documents. Could you comment on that?

NMYes, that's certainly the reality that I grew up in. The state archives, especially in the 1970s and 80s, had this very specific position. First of all, they were ignored and generally not considered important. There were many changes of government that were very rapid throughout the 1970s and 80s, and any new dispensation that came in had the assumption that there would be nothing in the archives that could be of any use.

The general attitude towards the archive was that the archives should be neglected and, in some cases, destroyed. Destroyed also by neglect, because they were kept in a humid environment, and that alone is enough to destroy the imprint of an event.

I think there was also something more active in the destruction of the archive. It's a great tragedy, of course, for anyone working in history. I grew up hearing from family members, 'My father gave this speech...' Or, 'There was this event and there was a cameraman, can you find that film footage?' I've never been able to find any film footage, which makes me think that either the person imagined it or the footage has been destroyed.

Our relationship to the archive has always been marked by this continuous erasure. You're trying to get to the archive before somebody makes it disappear. You're trying to make a work from it so that at least that newer commemoration of the original remains, even if the original archive disappears.

I have just done a project about indigenous people in the southeast of Bangladesh, the Chakma community in the Chittagong Hill Tracts, with my friend Tanzim Wahab, a curator based in Dhaka. It's a new project, and he said, 'You know, we are creating the documents.'

This video that we made, that he just curated for Chobi Mela, is going to end up being the only archive of this record. It is a video of myself and indigenous activist and lawyer Samari Chakma, reading from a book that she wrote.

The book contains oral histories of the indigenous Pahari, or Jumma community, that was flooded out by the Kaptai Dam in 1965. Most of the people that Samari interviewed have passed away, or soon will pass away. Her book is not necessarily widely available, although I hope it can be reprinted.

In the video, she and I are reading from the book as a live event. That reading, because it's captured on video, will probably become the document, because it will be available. There is also this document that we wish already existed. A timeline of the Kaptai Dam had to be created.

We have to create a parallel set of new documents and we do it within the forum of the visual arts, not necessarily of the academy. —[O]