Otobong Nkanga

Otobong Nkanga. Photo: © Wim van Dongen.

Otobong Nkanga. Photo: © Wim van Dongen.

Otobong Nkanga has developed a practice that reads the world on material terms and maps out how the body fits into a shared, earthly narrative. Her 2012 project Contained Measures of a Kolanut followed the artist's research into the library of CIRAD, the French Agricultural Research Centre for International Development in Paris' Bois De Vincennes, and the history and global impact of the West African kolanut. The performance follows the ritual of breaking open and eating the kolanut together with participants, and involves an invitation to select one of the cards that Nkanga prepared for the performance—prompts for oral storytelling surrounding the artist's research.

At the core of Contained Measures of a Kolanut is the consideration of a commodified natural resource—the kolanut plant was a key ingredient for Coca Cola and other caffeine-based soft drinks when they emerged at the turn of the 20th century. By creating an immediate encounter with a single resource that maps out an entire trade history, Nkanga diverts attention back to the material realities of a globalised present all too often understood only on macro-terms. The artist staged another version of the performance in 2012 as part of Tate London's The Tanks performance programme, which saw the artist sit at a table for nine hours and conversing with visitors who entered the performance space.

Art, for Nkanga, has been a way to think across borders and media, not to mention a way to understand her place in the world and what she should be doing in it. 'It's a very clear position,' she tells me on deciding to pursue art at the age of 15. Since then, she has studied at the Obafemi Awolowo University, Osun State, Nigeria, École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and the Rijksakademie van beeldende kunsten, Amsterdam, and completed Advanced Studies in the Performing Arts at DasArts, Amsterdam.

'My work is interconnected with the places I've lived. What happens in one place affects another. This is true for nature', too, Nkanga has said. 'There is no way of looking at the world in a little bubble. We have to look at all the different bubbles and how they are affecting each other.' Her 2007–2008 reinvention of Allan Kaprow's 1972 performance Baggage encapsulates the connectivity that Nkanga maps out. Kaprow's version involved transporting bags of sand from Houston, Texas, to a beach in Galveston, Texas, where those bags were filled with sand from the Gulf Coast before being taken back to Houston. Nkanga's version involved the artist's two homes: Nigeria, where she was born, and Belgium, where she now lives. She shipped bags of sand from Antwerp to Lagos and vice versa.

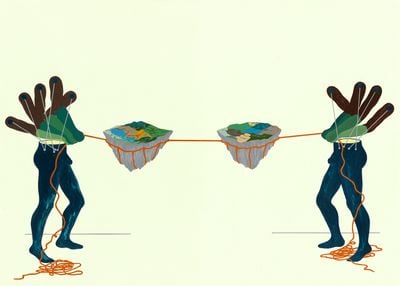

Movement as a contradictory—yet connective—dynamic is a core theme in Nkanga's work. In her drawings and tapestries, bodies, bodily parts and other forms become part of a vocabulary that describes how realities happening in multiple places intersect. In the acrylic and stickers on paper drawing Social Consequences I: Crisis (2009), two bodies with many arms in place of heads play tug of war with a rope that supports two islands on either side; while the large and beautiful tapestry The Weight of Scars (2015) shows these two figures standing on either side of a constellation with lines connecting orbs across the surface. The networks visualised in such illustrative works are likewise drawn out in sculptural form in installations like In Pursuit of Bling, which was first presented at the 2014 Berlin Biennale. Two large tapestries—one of a gemstone form and the other of a couple's legs—hang back to back in the middle of an arrangement of tables of various sizes and heights, on which geological samples, mineral pieces from copper and mica to malachite, archival photographs and texts printed on limestone are laid out. The work's title reflects the human tendency to turn nature into a commodity, while also taking into account the word 'Bling' as a contradictory signifier, which points to the shimmer of wealth and fortune, the affirmation of success, and the histories of colonialism and capitalist exploitation.

In Pursuit of Bling is currently on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago (MCA Chicago) as part of Nkanga's first survey exhibition in the United States, To Dig a Hole That Collapses Again (31 March–2 September 2018). In this conversation, Nkanga discusses some of the works on view in the show, while expanding on the ideas that run throughout her practice.

SBCould you talk about the meaning of the exhibition title for your show at MCA Chicago, To Dig a Hole That Collapses Again, which takes its name from the 'Green Hill' in Namibia; it is a direct translation of 'Tsumeb', the name of the town that houses that hill, right?

ONIt comes from the title of Tsumeb, but it was pronounced differently then and people imagined that this word meant to dig a hole that collapses again. Every time they tried to dig minerals from this spot it kept collapsing each time they dug the hole; and the Germans had the same problems when they tried to excavate the minerals there. I thought this was a good way to start thinking about the exhibition in Chicago and at the same time I expanded the title's idea into the way we are constantly building and constructing our histories in general—empires fall, new ones start again; something is constantly collapsing and we start again. It feels like history is a hole that we keep on digging, excavating, and building on—and then it collapses again, and something new starts again. This was the starting point to the exhibition title; this idea of digging a constantly collapsing hole as a way of thinking about history, or how we're making or doing things.

SBMicroscopic matter as a metaphor for existence runs through your practice. When describing a work like Baggage (2007–2008), for instance, you've said that a sand grain becomes a representation of the whole but the whole itself collapses into the representation of the sand: 'sand is sand whether it is here, in Congo or China'.

ONIn general we can talk about sand being sand, and it's then that we enter into the microscopic and into what it's composed of and where it comes from. From geologies we can think about technology, borders, land. I'm very interested in the microscopic and the general, and how those two things intersect and play roles and expand our understanding of what we are, somehow.

SBThat comes across in your representations of the body, particularly in your drawings. Some of your earliest drawings are now on view in your MCA Chicago exhibition for the first time, right?

ONDrawing comes from a place of imagination; it's where realities that are happening in multiple places can also intersect. Thinking about ideas of spirituality, magic, land, body, and fluidity, the show's curator, Omar Kholeif, and I thought to start from my drawing; so a lot of the earlier drawings on view are from 2009, which filtered memories and social consciences. Those drawings were looking more or less at my childhood, kind of as an extension of looking at the past, but trying to understand it through the acts that have affected you or have affected me. So if I don't remember a face or, let's say, the surroundings, but I remember a particular thing—that's what I precisely drew: gestures—people throwing water, for instance. But from those acts I then started thinking about what kind of consequences these kinds of acts could have, or how they connect to the wider world.

This is the first time I have really shown my drawings to the public, even though these are some of the earliest drawings I've done, and I've been drawing for a long time. There was more fluidity in the earlier drawings, which were much more about a sense of being without defining what a part of a body is doing, what it is capable of, and the power that it has. The later works are more focused on ways of thinking and making social or political gestures. If I make a hand, I really have to think, 'what is this hand?'—it is a way of thinking of a tool, a job, labour; I start giving a reference to the possibility of what a hand could be.

SBHow do the tapestries fit into this idea of drawing?

ONThe tapestries also come from this place of drawing, but I've always thought of tapestry as a way of reflecting within the African context, or the West African context, how textile or tapestries were also a way of communicating a message, as is the case with a canvas or even traditional indigo batik fabrics; they are always connected to a certain kind of history. If we look at the western context of the French or Belgian tapestries that adorned houses, for example, these were very much related to status and power and also related to ways of narrating a specific kind of history within that place. The combination of narration and projection makes it easy to shift from the place of drawing to think about how tapestries can be a way of thinking about social, economic, or political situations, but are also ways of adorning or warming up a space.

SBThis all really comes together In Pursuit of Bling, through which you were thinking about the changing forms of raw minerals as they enter into the processes of manufacturing, production and circulation.

ONThe thinking behind In Pursuit of Bling was this: we can think about malachite extracted and taken out from Namibia, and many other places like Congo, for example, and consider how these materials enter into architectural structures and also adorn and embellish the architecture. At the same time, we can think about that mineral, the copper, as a kind of material that transmits energy, just the way minerals like mica could be used to adorn the skin, as makeup—elements that reflect light on the body. One way of connecting all the things that are entering that space of light was to think about shine, which was the main thing that started coming out of the work. Then we started thinking about the shine of places and how, once emptied out, the light fades slowly; the energy is displaced somewhere else. So In Pursuit of Bling was not only about looking at that material sense of light, but also thinking about it in relation to spirituality and connection to a place, and how we can understand the notion of migration and displacement by thinking about a hole that displaces because of the removal of what it once contained. As the hole is made, the body is displaced.

SBThe displaced body was the focus of your performance Diaspore (2014), which entailed women carrying potted Queen of the Night plants on their heads as they walked over a topographical map drawn on the floor of the room. This was staged as part of 14 Rooms at Art Basel in 2014, curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist and Klaus Biesenbach and organised in collaboration with Fondation Beyeler, Art Basel and Theater Basel.

You have spoken about your performances as being drawings in space, which is also a good way to look at your installations. To that end, how does an installation like In Pursuit of Bling resonate with a performance like Diaspore?

ONI was working on Diaspore at the same time that I was working on In Pursuit of Bling. I was thinking about the relationship between bodies, plants, people, the notion of endemic plants, what belongs to a certain territory and what happens when that plant or that body is displaced into another territory. I was thinking about how the seed manages to have its relationship with the soil. How does that germination start? How much of a resistance does the soil have in relation to the seed? For me, it was interesting to think of the connection between the plant and the body. I always think about that struggle within that space in which the seed and the soil make a pact to allow it to grow. Through the notion of seeds splitting and dispersing into multiple places, we can imagine that some do die and never get to the destination they're meant to go, and others find possibility to grab on to and resist and also integrate within the spaces that might not necessarily be open to them coming in.

When I was working with Diaspore, thinking about language became very crucial when it came to thinking about the displacement or the movement of people. And once you start understanding these things through the rhetorics that are being used in politics or in political or social ways of describing things, then it makes sense to think of it in relation to the seed that splits in two, and how the spore has to resist against all odds in places that it finds itself in to grow. In terms of how this relates to In Pursuit of Bling: if we bring it back to that idea of something that finds itself in another place and has to find a way of being within that space, both are reflections on the movement of goods and people, trade, economy, material.

SBThat's a perfect way to think about your documenta 14 commission Carved to Flow (2017), which saw you set up a factory in Athens, where 'oils, butter and lye from all around the Mediterranean, Middle East, North and West Africa meet to create soap.' How did this project form, and how will it evolve? There are three phases: the third saw you establish The Carved to Flow Foundation in Akwa Ibom, Nigeria, which will aid in maintaining such initiatives as a non-profit art space and cosmetic lab in Athens, Greece, with curator Maya Tounta and soap maker Evi Lachana.

ONI got a letter in January 2016 from documenta inviting me to be part of it, and I visited the space on 25 March 2016. That was my first time going to Athens, but of course I had heard the stories about the extreme right, the financial crisis, and the influx of bodies and the death of people at sea. From the very beginning, I knew that I did not want to go to Athens to do something representational—it had to be something very concrete, and something that is close to reality and life. I was not interested in the idea of exploiting very clear political and social lines that we already know, but in how I could enter into a place that might refuse me.

The idea was that I would first start with the thing that actually produces an economy within that space, which was olive oil, the soil; to start from all the places that are not really explicitly talking about political systems, like the extreme right or left. One thing that made sense to me was this: if I think of the Mediterranean area, the Middle East, and North and West Africa, where lots of people are moving and shifting due to crisis and the different types of crisis that are happening there, then one of the things that connects all these spaces is oil. We could think of the oil underneath the sea or soil, or trees and plants. That's where the idea started coming together—what connects, not what divides, and to think about how people are escaping from places that are nourishing the world with their resources. These correlations between nourishment and impoverishment became a way of thinking through the process of this project.

Then there were also the architectural buildings that I visited in Athens. There was the Erechtheum, and its female columns—the Caryatids—and that understanding of the body as something that carries weight, their house on their heads, which led me to think about the migrants that are moving and carrying their last objects on their bodies, or the people that sell things on their bodies or on their heads. From there, it made sense to start thinking of what it means to carry life, and within that process it started to make sense that the project should actually carry life, and that life had to be connected to that notion of the economy and the body on all levels. I started looking at support structures, from things like grafting systems or pillarised societies, and entered into all kinds of ways of thinking about how one part could support the other.

It was important to think of the project as a holistic way of working; to think of the materials that we're using, such as plastic; about the waste that is going back into the soil. We made a clear decision to think about these factors at every single point in the process: the soap is a sculptural piece that will talk about the burning or charring of spaces that are also giving nourishment. Soap becomes a constellation of two worlds melting together to become a sculptural piece that can reflect on the soil, the earth, oil, wars, ecology; the soap itself opened up different topics of discussion, different ways of talking, and encouraged workshops that allowed people to think through the processes of making and distributing a product, and the displacement of bodies.

SBThis actually happened as a result of the 2015 Yanghyun Prize, right?

ONYes. The prize conditions were that the prize money should go to an institution in any part of the world to be able to make a solo show. When I was preparing for documenta it wasn't clear at all if there would be money to do the project, so I wrote to the foundation to ask if I could use the Yanghyun Prize money to do the project instead of a solo show, and they agreed. The project has three stages that are still continuing—it's now in the third, germination phase after documenta, in which a foundation has been opened in Nigeria.

But at the same time Carved to Flow is meant to be a way of thinking about how one creates and thinks about a sustainable way of making something without having to go through the process of looking through funds, and going through a structure that leaves institutions deciding if your project is good enough, and able to refuse funds to you at any moment. It was about thinking through the art structure so that there isn't a separation between the artwork and the notion of working with institutions that will then be involved. As much as my work has explored how the past has affected our present, at the same time it is also about how the past and present can be intertwined to open up the future. Three time frames are collapsed within a system of thinking.

SBThis relates to what documenta was trying to do within its capacity as a global platform through which bodies, people, objects, and histories circulate. But how the curatorial engaged with its host city, Athens, raised questions surrounding neocolonialist, or rather, neoliberal, approaches within the globalised art world.

ONI think if one has to get into a place and work with that place, one needs different ways of approaching the context and really reflecting on how to work with people, which is crucial. If thoughts of colonialism come in, there is definitely an issue from the past that hasn't been resolved in that place.

Being born into a colonised space, you learn a language that is not your language, and you have to master it because if you don't you will be accused of not mastering that language, even though it's not your own. You have to embody multiple worlds within a space that is colonised. So you understand the kind of fragmentation that takes place, the struggle that takes place within that and I think if you are aware and sensitive to that there are other ways of interacting within that space. But if you're not sensitive and you don't understand what it means to be in a space that is colonised, I think it's very hard to understand the subtleties and the things that are not said: the silences that are not being told.

SBYou have talked about how you deal with poetics as a means to represent bigger ideas that feed into your work; could you expand on how this approach manifests?

ONWhen I talk about being fragmented and coming from a colonised space, you understand multiple layers of being in different places. You learn how to be schizophrenic, and how to have multiple languages and voices; and you can use those voices at different times and at different moments. I think in relation to the work, I can enter a place of thinking from the perspective of my own ancestral family and spiritual land, and I can totally collapse it, layer it over, and think of it in relation to things that look the same but are not. In that way of looking through multiple layers and structures, you can collapse one thing into the other and flatten it to become one.

I don't really spend time thinking about the poetics, but there are multiple languages and multiple ways of how things can be said. In the work, this shows in the way that some things need a material form, others need a word in order to put it together, and other things need a gesture that allows that movement to amplify itself. But sometimes gestures can be tricky, we can understand certain gestures make sense across the world, and how to work with that; but to collapse them is to understand multiple worlds where everything comes together. This allows the images to take form in a specific way.

SBIt's nice to think about that in relation to the iteration of Contained Measures of Shifting States (2012) that you performed in The Tanks at Tate Modern in 2012, for which you sat at a table for nine hours engaging in discussion with people who visited the gallery.

ONIn 2012, I was invited to do this piece at the Tate in the frame of the politics of representation, and I was totally uninterested in the politics of representation, but was interested in talking about the politics of the things that we do not see, and the things that only manifest themselves in a time when you do not expect them to manifest. That's a way that I can understand, and maybe be at peace with, things that are manifesting themselves now, even with stories of Trump from the States—it's a manifestation of something that was already in place but is now taking shape and form, and we can see it in different cycles. So when we understand it as a manifestation that can disappear, it's just a moment of something with no fixed position.

Contained Measures started taking place around thinking about things that are dissolving and appearing. It was also one of the first times that I started using voice as a means of performance. To talk and connect with people over nine hours was crucial, because at this point in time we're talking about voice and the possibility of having a voice, and how the voice shifts perceptions, and how the material that appears as a result shifts in states of being. That's how the work started taking shape: thinking about constant performativity—body, voice, the elements, something melting, another thing infiltrating, and another thing evaporating.

What interested me was to think about the invisibility of things: water drops on a hot plate and it makes a sound—that's a manifestation with the sound and the smoke, and then it disappears. The voice has the same thing. We think that it disappears like smoke, but it doesn't: it just transforms into another state that we breathe in and which also changes our constellation of being. Once you say something to someone you don't know how much it affects that person, but it does have an effect in one way or another. I was thinking of that relationship with affect, which could be latent or not necessarily visible at that point in time; when something you say shifts into something else. —[O]