Renee So

Renee So. Courtesy the artist.

Renee So. Courtesy the artist.

Renee So's first institutional solo exhibition in Europe, Bellarmines and Bootlegs (8 March–2 June 2019) at the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds, centres on a long-standing motif in her work: the eponymous Bellarmine—a domestic jug used in the Rhineland in the 16th and 17th centuries to carry wine and beer from barrel to table. Following its spread across the rest of the continent, the stoneware vessel—adorned with an image of a bearded character from European folklore—eventually made its way into England's historical craft collections, including the Victoria & Albert Museum where the artist first encountered it.

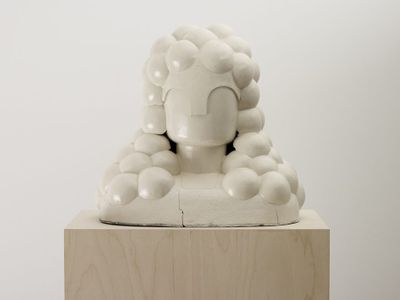

Bellarmines and Bootlegs includes 11 Bellarmine-inspired sculptures displayed on plinths. The terracotta-coloured Bellarmine with Bellarmine (2016) and the two pieces, Bellarmine X (2012) and Untitled (2012)—finished with a reflective metallic glaze that lends a lustrous quality to their profusion of baubles—are the few exceptions to So's mostly matte black sculptures. In Bellarmine XI (2013), So anthropomorphises the titular vessel by scratching facial features across its black surface to reveal its underlying off-white colour. The most recent of her sculptures, Bellarmine & Bootleg (2019)—a large circular black gourd-like base with an upturned boot placed atop—is positioned on a thin metallic tripod that, in turn, sits on a low-lying white plinth.

Alongside this assortment of sculptures, So has presented five machine-knitted tapestries in a mix of hues, from high-key jewel tones to earthy browns, greys, and beiges. Produced between 2012 and 2019, these wall-based pieces synthesise So's usual blend of influences, which includes Neo-Assyrian figurative statuary, cartoon animation, and the rotational symmetry of picture playing cards. Central to So's tapestries (or knitted paintings, as she sometimes refers to them) is the bearded male figure from the Bellarmine jug: depicted with a cane and top hat in Promenading (2010), as a face on two pairs of disembodied boot-bound legs in Sunset (2016), and as a toppled-over drunk with wine glasses for legs, surrounded by a shallow pool of wine in Drunken Bellarmine (2012).

Though born in Hong Kong, So was raised in Australia where she studied painting at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) during the mid-1990s, later moving to the U.K. in 2005 following a London Studio Residency with the Australia Council for the Arts. So's work has been exhibited widely in Australia and the U.K. over the years. She was most recently included in The London Open 2018 at Whitechapel Gallery, where she premiered a new type of work in the form of a tiled relief entitled Guitar (2018). Her most recent tiled compositions, Relaxation (2019) and Man and Dog 9 (version three) (2019), are exhibited in her current show at the Henry Moore Institute alongside Guitar (2018). All three combine the form of So's ceramic sculptures in the round with the stylised, cartoonish figures of her diagrammatic, wall-based tapestries. As a major inspiration for this new body of work, So cites the tiled murals in London's Underground tube stations including Annabel Grey's mosaic panels of hot air balloons at Finsbury Park. The work also draws significantly from the glazed brick bas-relief of the Babylonian Ishtar Gate (c. 575 BC)—once considered, as part of the Walls of Babylon, to be one of the original Seven Wonders of the world until the latter was superseded by the Lighthouse of Alexandria (c. 280 BC).

In this conversation, So speaks about her work in ceramics and textiles over the years, her residency at West Dean College of Arts and Conservation in the lead-up to her solo exhibition at De La Warr Pavilion, and the women of the Bauhaus weaving workshop whose influence on craft she hopes to investigate on the occasion of the famed German school's centenary.

TJMYou were born in Hong Kong but raised in Australia, which is where you went to art school—receiving your Bachelor of Fine Art in 1997. What was your experience of attending art school in Australia during that time?

RSI had a really patchy art education. When I graduated as a painting major from the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT), it was at a time when funding cuts were happening in arts education across the country. By my second year, the art school I was attending merged with another school and it became kind of chaotic. In my third year, I studied abroad as part of an exchange programme.

TJMWhere did you go during your time abroad and for how long?

RSI wanted to go to Los Angeles, and the school there that had a relationship with RMIT was the California State Polytechnic University, Pomona (or Cal Poly Pomona) in east L.A. I was only there for six months, but their academic year is split into four terms compared to two semesters in Australia. So those six months counted for two semesters' worth of credit and I graduated early from RMIT. That's partly what I meant by a 'patchy education'.

TJMHow was Cal Poly Pomona compared to RMIT?

RSI loved travelling so I enjoyed being outside of Australia. The arts programme at CPP was more traditional, which I appreciated because RMIT was going through its first wave of 'media art' and everyone was going crazy for video, so no one was actually painting. Painting was pretty uncool at the time and that kind of frustrated me. So going to this school in Los Angeles, where I did life drawing, painting, and stone carving for my sculpture course, was a welcome change. The experience was short, but it was good.

TJMHow did you sustain a livelihood after graduating? What kind of work were you making?

RSI graduated in 1997 and floated around doing part-time jobs, went on the dole ... I was living a very care-free bohemian life. Times were different, which meant I could live independently in the city. I was also making art, of course. The work was similar to what I do now, but I was hand-knitting instead of machine knitting—mostly small things that I turned into installation art. I wanted to scale things up to make installations, but it was really difficult to knit everything myself by hand.

TJMHence the move to machine knitting...

RSActually, before the machine-knitting, I had these large knitting needles that were thick wooden dowels for 'giant knitting'. So for some time, I was hand-knitting the same stuff as before, but using thick wool and thick knitting needles to enlarge everything.

TJMThen in 2005 you undertook an Australia Council – London Studio Residency. How long was the residency and what made you relocate permanently?

RSMy husband (then-partner) and I both came to London during my Australia Council residency. But before we came, we had already made plans to move. We were living in my aunt's house while she was overseas and shortly before that we had just travelled around the U.S.A. and Europe for around three months—so we had moved out of our previous home and were already itinerant. While we were travelling, we had the idea to 'move somewhere' and so we applied for residencies to see what would come up. So the move to London was part of a plan and at that stage we were young with no furniture to ship. We left with a suitcase each.

TJMAt what point did you introduce the Bellarmine and what drew you to it?

RSI discovered Bellarmine jugs in the U.K. at the V&A, which is a decorative arts museum. Initially, I wasn't in love with the pot, but I was drawn to its history, material, and the bearded face that each one features. I had been looking at classical sculpture—roman busts—and their rendering of beards, hair, and torsos. The bearded man on the Bellarmine jug was not distinguished, but actually a bit wild, and definitely on the lower end of culture, as they were beer mugs. Originating in 16th- and 17th-century Germany, and exported all over the world, they were a common household object and widely used to store wine, beer, or oil from the barrel to the table. They are ceramic, which is a medium I was working in, so it was a case of coming across something I connected to thematically and materially and could appropriate. Its history gave it authenticity, being named after an unpopular Cardinal of the time, Robert Bellarmine, which led them to be used as 'protest pots' against differing religious values—Catholic versus Protestant. And as a mass-produced functional vessel, it fell into the genre of 'craft'.

TJMThere are a few of the bellarmine's uses that I have only just learnt through your show Bellarmines and Bootlegs at the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds, including its use as a 'witch-bottle'.

RSThat is something about the Bellarmine that I am yet to explore but I would like to someday. In some displays, they show x-rays in which you can see the contents of the old Bellarmines, once used as witch-bottles. It was usually human hair, nail clippings, or blood placed in a Bellarmine, which was then buried beneath someone's property.

TJMAnd in your own usage, did the Bellarmine emerge concurrently in your machine-knitted tapestries and in your sculptures?

RSIt emerged in two dimensions: first as a drawing, then as a sculpture. I adopted the pot-bellied shape and the bearded face of the jug into a figure and then I gave it arms and legs. I then made the connection that the human body was also a vessel for alcohol, so the figure and the jug became the same thing. A bulbous pot with human features and legs, filled with wine or beer, is exactly what a drunk and bloated man is.

TJMThere is a certain wry sadism—a kind of physical comedy—to many of those images. For example the figure with wine glasses (or goblets) for legs toppling over in Drunken Bellarmine (2012), with spilt fluids—maybe blood, maybe wine—all around him. It has an air of slapstick to it. Are these intended as parodies of masculinity?

RSNo, they actually aren't, although I can see how they could be read that way. When I moved to London, I was shocked at how much people drank—both men and women. I felt a pressure to keep up and do the same, to terrible effect. I think of them more as observations of drunken behaviour rather than parodies, and the transfer of alcohol from vessel to body; the cause and effect. The way that men try to project power—mostly, but not exclusively—in Western portraiture is also something that I have highlighted, but not necessarily parodied. The curly wigs, beards, top hats, boots, tights, and canes have always looked like props to me. The knitting process and texture is what gives the images their comical, cartoon-y style.

TJMAs you say, you were drawing from Roman busts, along with civic and military representations depicting men of rank. How did the Assyrian sources start to influence your work?

RSWell, again, I discovered Assyrian art at the British Museum when I first moved to London. The Assyrian Empire developed from old Mesopotamia, an area in the Middle East that spans modern-day Syria, Iraq, and Iran. Before this, I was really only thinking about art history in terms of East and West.

I was drawn to the depictions of men with tightly curled beards. The beard in Assyrian art was a symbol of masculinity and power, reserved only for kings. Eunuchs were always portrayed clean-shaven. I liked the way that the beard both dominated and obscured the face, but also looked 'stuck on', especially in profile. In the studio, I developed a method of wrapping clay around a golf ball, which I then cut and assembled to make a curly beard that merged with the hair to make a single shape. This was technically really challenging—but also very satisfying—which is another reason for my concentration on the beard.

TJMOn a smaller, more personal scale, you've had to look closely at the history of your own work while putting together your solo exhibition Bellarmines and Bootlegs at the Henry Moore Institute. Tell us about this process and whether or not you went in with criteria for selecting work to be included.

RSThe show was narrowed down to the Bellarmine series because it sustained me for so long, but we were also limited to work that was located in the U.K. There was some work in Australia that I would have loved to include, but logistically it was not possible. Most of what I wanted to include is there in the exhibition. And where I saw gaps, I made new pieces to fill them.

TJMThese newer pieces include a trio of tiled tableaux in relief. Formally, they sit somewhere between your tapestries and your sculptural bust and boot ceramics. I first saw one of them in The London Open 2018 at Whitechapel. In your conversation with Jennifer Higgie, in the exhibition's accompanying booklet, you mention the London Underground as a source of inspiration. Can you tell us a bit more about these newer pieces?

RSI'm really enjoying making tiles at the moment. They are really fun! I'm always paying attention to what's going on in Tube stations because entering one is like going through a tiled maze. They all have such different characters—some of the tiling in the tunnels is very worn out and discoloured, some are purely utilitarian, and others are brand new and very decorative. I'm interested in all those variations. Annabel Grey's beautiful mosaic panels of hot air balloons at Finsbury Park are my favourite, and Eduardo Paolozzi's mosaics at Tottenham Court Road are also up there. My local station, Haggerston, also has a new large-scale tiled mural.

TJMAnd when you're making your own sculptures, what is it like to go from the stage of an idea to the moment of glazing?

RSEverything starts off as a very rough sketch and translating this into three dimensions is the exciting and challenging part. I always make the mistake of thinking that when I finish hand-building a sculpture, it is done. But it isn't finished until it comes out of the kiln. That is the make-or-break moment when the clay becomes stoneware, or when the firing process exposes some technical flaw for all to see. It can be very depressing when something goes wrong, but also miraculous when something that I thought would go wrong, survives. Lately, I have given up glazing to streamline the process, as firing makes me anxious. Especially when things go wrong after the second firing—that just isn't fair! I've been using a pigmented black clay that fires black or I use regular clay and stain it black afterwards. The benefit of working with tiles is that if something doesn't work out, I just remake that tile, as opposed to writing off the whole thing.

TJMI know the intarsia knitting process you use is more mechanised than working with clay, but it is still quite involved and laborious. Can you describe your equipment and how you build the images in your 'knitted paintings' or 'tapestries'?

RSI start with a drawing—often very basic—which I import into Photoshop, where a lot of the flipping and repeating of forms happens. I use different layers and try out different colours, then I put a grid over the finished image and that becomes the pattern I follow. I've recently made my own knitting machine. Or stripped one back, I should say—that's more accurate. I wanted something extremely minimal since I wasn't using the majority of functions and it was encased in horrible yellowing plastic. As it is now, the knitting machine has a metal bed with 200 needles, a carriage that you run across, back and forth, to knit a row, and a row counter. You lay the wool over the needles and when you want to change colour, you put the right coloured wool along the bed to the point where you want it and then grab another colour, lay that down and run the carriage across. Each piece, at the size I currently make them, is 800 rows in height and the width of two 60-centimetre (or 200 needles) panels joined together.

A lot of people think machine-knitting is an automated process and that everything happens digitally, but that is not the case. Knitting machines are no longer part of everyday domestic life in the way they were in the seventies and eighties, when women—usually housewives—made items for the home and clothes for their families. The role of women has changed significantly since, and you also don't have to make these things anymore, as knitwear has become more readily available and affordable.

TJMWhich leads to my next question on craft and gender. For your forthcoming residency at West Dean College of Arts and Conservation, in the lead-up to your solo exhibition at De La Warr Pavilion in September, you're looking at the legacy of the Bauhaus on the occasion of its centenary. But, more specifically, you're interested in the women who were in the weaving department, like Anni Albers, Benita Koch-Otte, Gertrud Arndt, and Gunta Stölzl.

RSAfter the women who were enrolled at the Bauhaus finished their foundation course, they went to specialise but were refused their choices and steered towards the weaving department. This attitude says so much about craft, gender, and 'women's work'. Interestingly enough, weaving was the most commercially successful department of the Bauhaus. It helped fund the school even though it was never prioritised or taken as seriously as the other departments.

I'm interested in the Bauhaus weavers because of their relationship to how I work. Initially, my work was inspired by medieval tapestries and machine-knitting was the closest way I could get to something pictorial. I've wanted to learn weaving for about ten years now. I've just bought a loom and I'm teaching myself in the lead-up to the residency and exhibition. West Dean is an arts and crafts school with a ceramics department and a world-class tapestry studio—the two media I almost exclusively work in. The residency itself is short: three weeks starting in April. The exhibition at De La Warr Pavilion in Sussex opens this September, and so I'm still trying to form what the show will be. It will be along the lines of functional sculpture with weaving as a core element.

TJMI want to end with your thoughts on change—that is, the shifts you've witnessed in the relationship between craft and what has been historically called fine art. Books like Vitamin C: Clay and Ceramic in Contemporary Art by Clare Lilley and Vitamin T: Threads and Textiles in Contemporary Art by Jenelle Porter—both of which include your work—attest to the playing field's gradual levelling. Is this something you've observed?

RSI think contemporary art is embracing craft a lot more, although it seems to have been rebranded as design. I noticed, maybe ten years ago, more artists working in ceramics being represented at art fairs, and now it's seen as contemporary and is widely accepted. The same goes with tapestry and weaving—I'm seeing it a lot more in galleries and art fairs, and the last Venice Biennale had a very strong showing of fibre art.

TJMAnd generationally, would you say there is as much re-evaluation of those who were dismissed historically as there is support for younger, emerging practices?

RSThere is a huge respect and appreciation now for the previous generation of weavers, potters, and ceramicists—they are seen as pioneers and have gained a whole new audience for their work, although often very belatedly. Perhaps craft and working with one's hands is the antidote for our technological age. I have observed more male artists taking up weaving and ceramics too, so we're gradually starting to get rid of the gender divide. —[O]