Rirkrit Tiravanija and Hans Ulrich Obrist in Conversation

In collaboration with STPI – Creative Workshop & Gallery, Singapore

Left to right: Hans Ulrich Obrist; Rirkrit Tiravanija.

Left to right: Hans Ulrich Obrist; Rirkrit Tiravanija.

Rirkrit Tiravanija's latest exhibition in Singapore, curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist, is a dark prophecy of the impending demise of human civilisation.

Presented at STPI – Creative Workshop & Gallery in Singapore, We Don't Recognise What We Don't See (8 April–4 June 2023) debuts 40 works by Rirkrit Tiravanija and is the result of a continuing relationship that has seen him undertake three residencies over a period of 10 years, enabling him to work collaboratively with STPI workshop to explore print and papermaking materials and techniques.

Tiravanija's first residency in 2013 took Charles Darwin's Tree of Life, which maps and names all biological life, as a starting point, while a residency in 2015 with Anri Sala, Tobias Rehberger, and Carsten Höller saw the four artists work collaboratively on collective works, using the premise of the exquisite corpse game as their impetus. The game was originally adopted by the Surrealists to collaboratively produce work and involves each participant taking turns writing or drawing on a sheet of paper, folding it to conceal his or her contribution, and then passing it to the next player for a further contribution.

For this 3rd residency, Tiravanija's focus is on a world where all species—including humans—are at risk of extinction; a fitting subject in a world where climate change, shrinking and degraded habitats, and a general lack of care continue to diminish the planet's natural and animal worlds.

In 40 new works that use various printmaking techniques, Tiravanija dwells on the realm of the disappeared, the absent, the lost, and the other as a means of proposing individual and collective responsibility. Throughout the exhibition, the artist interrogates the idea of 'the other' that has been imposed on non-human species, and advocates instead for the interconnectedness of species.

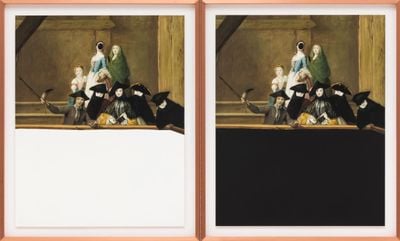

For the untitled series of five works—colloquially named the 'Old Masters' series (2023) by Tiravanija—loss and its attendant grief are illuminated through the artist's use of UV, thermal-activated-ink prints, on view when first entering the gallery space in a room painted a dramatic red. As the starting point for these works, Tiravanija appropriates paintings by Old Masters, removing most living creatures and screen-printing extinct or soon-to-be extinct animals in their place using ink only visible when activated by ultraviolet light. The works are a fitting analogy of human neglect and disinterest, something the title of the exhibition also references. In his shining a light on extinction, Tiravanija asks his audience to become interested, to learn, and to care.

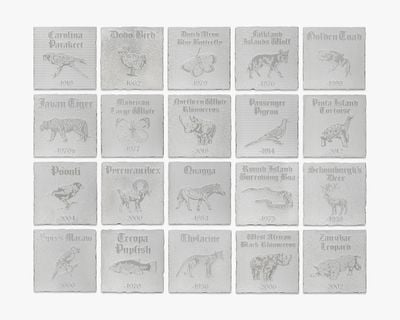

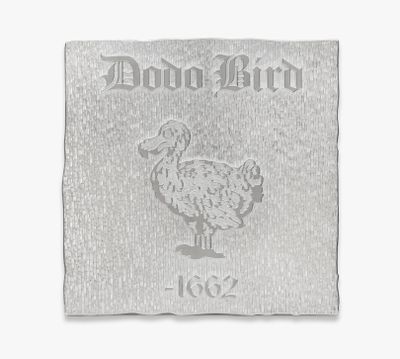

Another series, 'untitled 2020 (nature morte)' (2023), gives audiences this opportunity. In a confronting display, 20 monuments for 20 extinct animals are engraved on aluminum plates and arranged in a graveyard setting. The audience is invited to participate and create rubbings from the plates, and in these repeated actions they become integral in spotlighting the extinction crisis; each rubbing an act of re-creation.

In the following conversation, which is an edited excerpt of one that took place between the artist and curator on 13 March 2023, Tiravanija and Obrist trace the origins of the idea for We Don't Recognise What We Don't See back through previous residencies at STPI and other projects.

The two discuss what it means to be an artist; a role that goes beyond personal creative and aesthetic decisions to a responsibility as a voice for the voiceless. Tiravanija hopes that the exhibition can be a space for audiences to reflect and remember what has been lost, and '... where you can experience otherness without fear ... where you understand yourself more so that you're able to be with the otherness.'

HUOToday we're talking about your 'Extinction' series in We Don't Recognise What We Don't See, premiering at STPI.

Can you talk a little about how this 3rd residency at STPI grew out of your 2nd residency there in 2015 with Anri Sala, Tobias Rehberger, and Carsten Höller, and also how the exquisite corpse game came to be used as a mode for making?

RTYes, we went to Singapore to do a work together and, in that context, we realised that one of the ways we could collaboratively work, when we were together or apart, was through the idea of the exquisite corpse game. So, we made formats and decided that each one of the four of us would start one and then pass it on in rotation to each person. And, of course, whoever starts makes the rules of the game and determines how the print will be made. I think it was Rita [Targui] who came up with a new game—who asked us, if you were an animal, what would you be?

HUOI remember. Because you wanted to be a fruit fly. [laughs]

RT[Laughs] Exactly. I wanted to be a fruit fly. I can't remember what everyone else chose, but because of the exquisite corpse game and Rita's game, I started to make—almost separately from the game—portraits of some of those animals. So, that's partly how the theme of other species came up, and from there it started to evolve—there was a lot of discussion about extinction and thinking about interspecies.

We take other species and otherness for granted simply because we misunderstand or we don't have any experience. I hope that this exhibition will point to that idea.

HUOYou read an article at the beginning of this endeavour—an 'Extinction Obituary' in The Guardian for the quiet and beautiful Hawai'ian po'ouli bird. The last of the species died in 2004, despite attempts to find it a mate, and it died in a small towel twisted into a ring that scientists made for it because it was too weak to perch—it's a very sad article.

So, was that a kind of beginning?

RTYes, there were a lot of stories about extinctions. There was one about a white rhinoceros that was the only male rhino of that particular sub-species left. So, yes, it's sad—that idea that you are the last of your kind and there is no possibility to continue your species.

HUOThere's a quote that you use a lot in your paintings: 'The days of this society is numbered' ...

RTYes, I'm dealing with this feeling of helplessness. A feeling I think is experienced by a lot of younger people, especially.

HUOAnd another quote you use, which also connects to this project, is the Hawai'ian proverb Hāhai nō ka ua i ka ululāʻau, 'The rain follows the forest'.

RTYes, we are all talking about ending the use of fossil fuel, but we're not really thinking about, for example, the scarcity or the quality of water; an issue that is going to affect everyone much faster than we think.

I was visiting the show of a friend of mine recently—Minerva Cuevas' at Kurimanzutto [in gods we trust (3 March–15 April 2023)]—and she has collected all these advertisements from the 1940s and 50s, many made by oil companies. And some of these adverts are talking about how the energy supplied by petroleum would be enough to melt glaciers; naively suggesting this as a positive. So, it's interesting how we're slowly learning that the things we thought were going to make a better world for humanity are actually killing the planet.

HUOThat's something the German artist Gustav Metzger used to say. I think the spirit of Gustav is present in your show at STPI. Gustav once told me that as artists we need to take a stand against the ongoing erasure of species, even if there is little chance of ultimate success. It's our duty to be at the forefront—our privilege and our duty to be at the forefront—of this struggle by humanity. He used to say that speed was of the essence. Was Gustav important for you?

RTI didn't know him well, but, yes, I'm aware of his work and his words. You talked a lot with him. I met him when he was taking part in the Extinction Marathon at Serpentine in 2014.

It's about relationships; if we don't have experience with something we tend to not understand or think about it.

HUOYes, he did the Extinction Marathon at the Serpentine.

Let's talk some more about your beginnings. I found a publication that relates to a project you did with Philadelphia Museum of Art; let's talk about that influence.

RTYes, Philadelphia Museum of Art approached me to do a project1. And at that time, I was starting to work in Thailand and had been at Chiang Mai University doing some workshops. The younger Thai artists look to the West as a model, in terms of the idea of artmaking, and I wanted to find a way to bring them to the U.S. to have a real experience with what they had been looking at or studying—their heroes, models, and references. So, I proposed to the museum that I bring a busload of people.

In the end, we brought five young artists. I took them to Los Angeles because it was the closest port of entry from Thailand but, also, with this idea of a reverse trip—we went from the west to the east of the country—and my plan was to stop and see various works of art on the way.

I wanted the last work they would see to be Duchamp's Étant Donnés, which is in the Philadelphia Museum—it's at the end of a hall, right at the end of the museum, and the work is this little old wooden door with a little hole to look through where the viewer can see a prone female nude half buried in bracken, holding a lamp, with a classical landscape in the background.

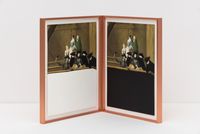

HUOAnd I remember the exhibition catalogue [from Museum Studies 4: Rirkrit Tiravanija]—three slipcase, passport-style volumes with sketches and materials. It's sort of the model for the catalogue for this STPI exhibition?

RTYes, I have always liked showing the working, the research, as such.

HUOAnd that leads us to the untitled 2020 (extinction series) (2023), which is at the centre of this exhibition. Some of the first works you created in the series are these origami works, folded and then unfolded prints of endangered species.

RTYeah. When I first started working with printmaking at STPI I discovered this thermal ink that is activated by heat. It's used commercially to indicate the shelf life of a product, so when the colour of the ink fades you can see through the label, indicating that the shelf life of that object has expired.

I'm always very interested in keeping things alive or active, but, of course, within that idea, that relationship, there's a beginning and there's always an end; it's a life cycle of its own and I guess it has its metaphors. I was very interested in this ink. And then in that process we also discovered another kind of ink, one that does the opposite; an invisible ink that only appears with sunlight. So, both are very much about temperature change: in the future when the world becomes too hot, the thermal ink will fade to make everything visible, while the UV/invisible ink will appear, also revealing what has been hidden. So, these inks are chemically activating the concerns that we have about temperature change and how increased UV will affect everything.

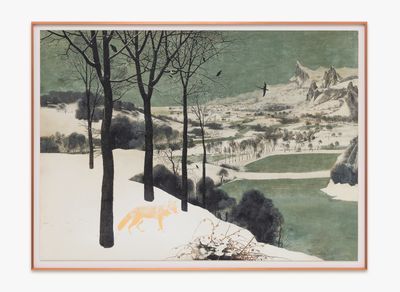

HUOYou revisit this idea in this exhibition with the series that works through Old Master paintings; for example, through Pieter Bruegel's Hunters in the Snow. In these works, you have removed almost all life. Can you talk about this?

RTYes, for these works I removed 'non-human' life through a chemical process, so you are only able see the 'other' living things in certain conditions—that is, if you shine a particular kind of light on the work.

If we look at how the West has colonised and gathered information and knowledge, for example, through the idea of the zoo ... it's a collection or a library of otherness. I remove these things from the paintings. For Bruegel's Hunters in the Snow, I inserted species into the landscape that are going to be or are already extinct.

It's relevant to the title of the show, We Don't Recognise What We Don't See. It's about relationships; if we don't have experience with something we tend to not understand or think about it. We don't think a lot about the fruit fly until it starts to fly around the fruit on the table. We never really try to understand why, how, and what it means that the fruit fly exists, or what are the implications of its existence. So, in that way, we do take a lot of things for granted; we take other species and otherness for granted simply because we misunderstand or we don't have any experience. I hope that this exhibition will point to that idea.

HUOIn the exhibition, there is also a whole participatory room where the series of works titled (untitled 2020 (nature morte) (2023) is located, offering visitors the opportunity to think about extinct or endangered animals and make their own rubbings and drawings from these prints. Can you talk about this very central room in the exhibition?

RTWell, it's really a graveyard of species that are extinct, and as in graveyards where famous people are buried and people make rubbings of the headstones, visitors are invited to do that here. In terms of this work, I would really like younger people to have the experience of getting close to these animals, for people to become more curious and inform themselves.

HUOIt's also a memory work, in a way, because we live in a world where there's more information but there's also more memory.

RTYes, I think that's a very important aspect of the work itself; the idea that if something doesn't exist anymore how do we remember it? How do we remind ourselves that we have to think about these kinds of losses? These animals are not able to say anything to us, they're not able to stand up and say, we want you to stop, or we want you to do things differently, so we need to listen.

I think the more interaction we have and the more we try and understand, the better. We've built a lot of machinery to distance ourselves from these kinds of experiences and memories. I think that's something that art can do; remind people that there is that space to understand.

HUOAnd, I think, also create empathy ...

RTYes. That's probably one of the more important things, now more than ever, that we need in the world. We have had some discussions at school about the idea of cancelling, of erasure. I said to some of the students2 during the discussion that an erasure is not really fixing anything. In that erasure you void yourself of compassion and empathy, from understanding that, yes, there are good things in the world. There are also bad things in the world, but if there are only good things in the world it's impossible for you to understand that, really.

I'd like art to be the place where you understand yourself more so that you're able to be with the otherness.

HUOYes. I wanted to ask you, what is the definition of art? I've just been listening to the poet Jane Hirshfield and she said poetry is the attempt to understand fully what is real, what is present, what is imaginable, what is feelable, and asking, how can I loosen the grip of what I already know and find some new, changed relationship. She says through poetry she knows something new and is changed. It's a beautiful definition.

How do you define art?

RTWell, I think of it as a space, a space where there is no limitation of ideas, and it is always free and not consumable. From my perspective, I would like it to be a space where you can experience otherness without fear and without the burden of your own history. Of course, it's really difficult for people to understand themselves enough to not be afraid; we're afraid because we don't understand ourselves, not because we don't understand the other. I'd like art to be the place where you understand yourself more so that you're able to be with the otherness.

HUOAnother question, which I always ask, and I've asked you many times before, is the question of the unrealised project. We cannot have this conversation without addressing it once more. Unrealised architectural projects are often published—through competitions, for example—but we know very little about the unrealised projects of visual artists, poets, novelists, and scientists. There are several reasons why projects are not realised: they might be too big, expensive, time intensive, impossible to build, and then, of course, censorship and self-censorship can be reasons—maybe there are certain projects we want to do but we don't dare. So, within this range, I wanted to ask you about one or two of your favorite unrealised projects.

RTOne was in Thailand. There was a lot of political action going on at the time and I wanted to make a film on every type of person in the country and ask each of them a few questions, just to see where everyone's thoughts were about being together or not being together.

HUOAnd that's unrealised?

RTYes. I have started to think more and more about doing things that are, I wouldn't say unrealised. It's not about it being unrealised but about it being realised very slowly and through actions one can do every day. For example, I smile at everyone I meet on the street and, regardless of the situation, that's something you can do everywhere, all the time, any time. And maybe it's never realised in the sense that one doesn't really know what it is. —[O]