Shubigi Rao Maps Linguistic Diversity at the Venice Biennale

National Arts Council Singapore | Sponsored Content

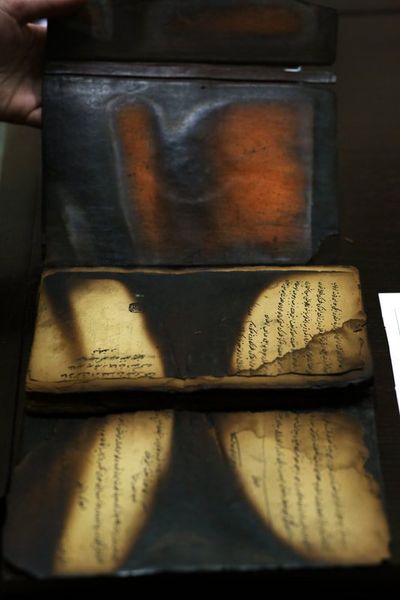

Courtesy the artist. Photo: Kathrin Leisch.

Courtesy the artist. Photo: Kathrin Leisch.

In 2002, Shubigi Rao relocated to Singapore, having completed her BA in English Literature at the University of Delhi in 1996.

It was there that she encountered a graduate exhibition at LASALLE College of the Arts, which led her to complete her BFA at the school in 2006 followed by an MFA in 2008, consolidating visual and material means to reflect her longstanding interest in literature and the physical manifestations of human civilisation's outputs and erasures.

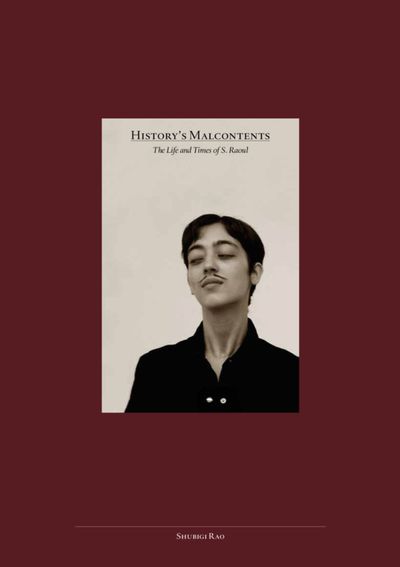

During these early years, Rao assumed the fictional identity of S. Raoul, under which she delved into archaeology and neuroscience. 'I was in the space of science, art and writing,' Rao has explained, 'and the nexus between these arenas is very loaded against women, and I had to prove a point.'

Among early works was The Study of Leftovers (2003–2004)—an installation of objects, drawings, and etchings that formed an archaeological study of organic and non-organic life from Singapore as if the nation-state were extinct.

Elsewhere, pseudo-science was employed in tongue-in-cheek presentations such as The Tuning Fork of the Mind (2008), in which 'damage' caused to the brain by art was sonically translated by a machine connected to headphones in the exhibition space, as a reflection on the way contemporary art was being frequently dismissed in mainstream media at the time.

The death of S. Raoul—who tripped over an installation 'and broke his neck while attempting to negotiate space in a cultural context'—occurred in 2013 with an exhibition at Singapore's Earl Lu Gallery, forming a fake retrospective of S. Raoul's work while marking the end of a decade-long feminist act.

'It was also an act of anti-censorship in a way,' explained Rao, 'For 10 years I did not have a solo show. I lit a match to my career. All the women who, through history, have watched others steal their spotlight, I made it happen to myself.'

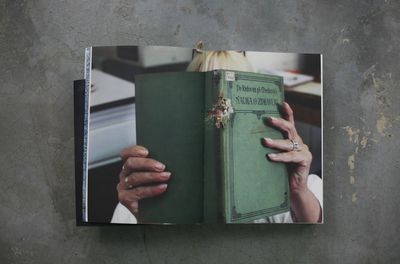

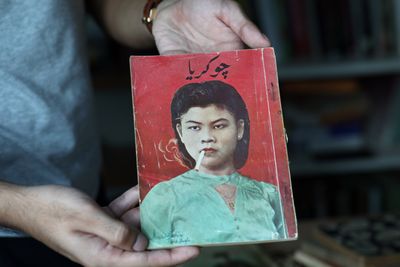

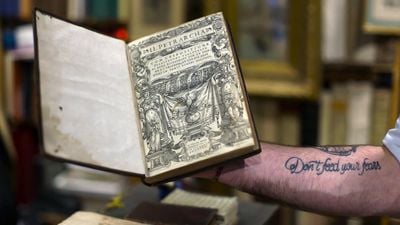

Acts of repression have become central to Rao's current long-term project, Pulp: A Short Biography of the Banished Book, which looks into the destruction of libraries and books and how these acts of violence are impacting the futures of knowledge.

Rao has been working on the project since 2014, piecing together ephemera and anecdotes into a 'composite chronology of the conjoined literary and violent trajectories of our species'. Taking book form, with the most recent volume having received the 2020 Singapore Literature Prize, Pulp: A Short Biography of the Banished Book also comes together as films, artwork, and installations.

Rao will represent Singapore with the project at the 59th Venice Biennale (23 April–27 November 2022), with Ute Meta Bauer—founding director of NTU Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore—curating the presentation, marking the first time a women-led team will represent the country.

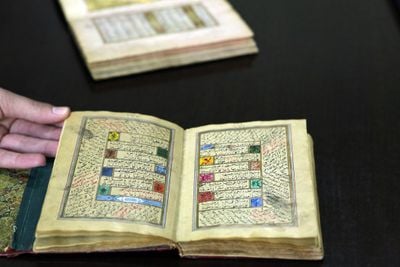

The Pavilion will be formed of a paper maze, book, and film, looking into print communities from around the world including those of Singapore and Venice, in particular the Kristang—a community of people with Portuguese and Malay ancestry in Singapore—and Cimbrian, an Italian ethnic minority present in the Veneto region.

At its core, Pulp: A Short Biography of the Banished Book is a collaborative project, bringing together custodians of culture—including librarians, printers, writers, academics, and more—to consider future modes of conservation for endangered languages.

In this conversation, Rao introduces Pulp's trajectory thus far, and how the project will take shape at the Venice Biennale.

TMUpon relocating to Singapore from India in 2003, you began conducting research into archaeology and neuroscience under the persona of S. Raoul.

Early works under this persona include The Study of Leftovers (2003–2004), which assembled detritus collected from around Singapore as if the nation-state were extinct, and The Tuning Fork of the Mind (2008), based on a 'pseudo-scientific theory of brainwave activity' that you developed to consider what happens in a viewer's response to art.

What led you to create this persona and subsequently drop it in 2013?

SRS. Raoul was a male polymath, a persona created from 2003 to 2013 under whose name I wrote and made art. It was also my first ten-year project. As part of this persona, I operated as his protégé, biographer, and eventual custodian of his posthumous archive.

This was an important feminist statement for me as well. I did not have a solo under my own name for ten years, choosing instead to make work under his, as a way to examine the exclusion of women from art history, and from so many contemporary spaces at the time.

My first solo was a fake retrospective of his work at the end of the decade-long project. The S. Raoul project was also an evisceration of the ascribing of genius in the polymathic, eccentric male, while similar nonconformity is described as madness in the female.

I've always been fascinated by the act of biography as reclaiming one's place, or claiming someone else's story, and this had a significant impact on the Pulp project. In Pulp, the book is a personification, and therefore the work operates through the medium of biography.

In short, it is a retelling of the histories of our species, and our warring propensities to create and destroy, all through the lens of the book.

TMPulp: A Short Biography of the Banished Book represents a continuation of your expansive approach to media, encompassing film, drawings, and written material.

In this project, diverse threads of research come together to explore the disappearance of language. How exactly does language vanish?

SRLanguages vanish for a number of reasons—from neglect, forcible displacement of people or migration away from linguistic communities, the dominance of national languages, the disappearance of threatened or minority languages from classrooms, libraries, and other educational arenas.

With the loss of a language every fortnight, linguistic diversity continues to be threatened across the world.

The lack of economic power in marginalised communities also leads to a loss of younger speakers to urban centres, while that same economic lack means the resources necessary for the survival of language and cultural continuity are absent.

TMWhen is a language dead? What does this mean?

SRLanguage begins to disappear when fewer people think, write, or read in it, and are no longer taught it. Language also vanishes when it is no longer spoken, because it is regarded as irrelevant compared to English or other dominant languages.

With the loss of a language every fortnight, linguistic diversity continues to be threatened across the world. Libraries can serve not only as holders of endangered languages, but also as places of reactivation of them and their communities.

Local and community libraries are vital in efforts to preserve and consolidate, plus also grow and encourage new thought, new writing, and new forms of language integration.

TMCould you give us a taste of how this 'lyrical manuscript' will be translated in the space? What are your strategies for cohesion when dealing with a lot of different material?

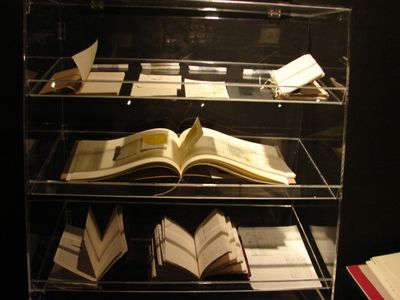

SRThe exhibition space is composed of three main elements: a paper maze, book, and film. As the visitor enters the paper maze, they will see a lyrical quote, which includes a large drawing as a poetic mapping of the key junctures and notes of the project.

Sound plays an important role, as it is one of the first elements the visitor interacts with even before entering the space. In a way, it creates a certain imaginary of the space they are about to enter, and encapsulates a physicalised experience of reading.

The paper maze and unfolding of the exhibition encourages time to slow down, similar to the experience one has through the act of reading.

In close collaboration with my curator Ute Meta Bauer and exhibition designer Laura Miotto, we meticulously worked on every element of the exhibition to ensure these disparate media and forms connect with each other, but are still distinct and wholly realised.

TMIn the past, you have incorporated materials of historical significance such as cinnabar, recalling its use in book production. What kinds of materials can we expect to encounter in Venice?

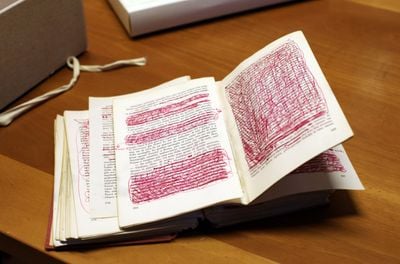

SRThe cinnabar-like colour that appears throughout the Pulp books owes its provenance to the naturally occurring vermilions and reds used in the early days of book printing, when the colour represented the midpoint between the negative white of the page and the positive black of type, making it the ideal accent colour.

Before the invention of movable type, copyists in scriptoria throughout Europe also used red iron oxides and the more costly vermilion—almost as expensive as gilding—in manuscripts.

The Romans favoured a cheaper minium, or red lead; pricier cinnabar, which is still visible in murals in Pompeii; and, according to Pliny, the even more expensive red ochre Pontus Euxinus, with the best red clay coming from the Pontine city of Sinope.

The oldest reds are, of course, the ochres of ferric oxide—laden clay, used as early as 35 to 40,000 years ago on cave walls in El Castillo, Spain; Lascaux, France; and Maros in Sulawesi, Indonesia.

Repetition, when it occurs, is not tedious but reaffirming, as when dissimilar people from vastly different milieus demonstrate a similar passion for a text.

The blue colour of the interjections-as-marginalia is a reference to the 'blue pencil' used by editors and copyeditors for markup, and queries to the author regarding narrative voice, tone, and content. Blue was historically chosen as it would not be visible in the final print during certain traditional lithographic and photographic procedures.

These aspects were collaboratively developed and exquisitely incorporated in the books by my book designers and long-time collaborators, Benson Chong and Felix Sng of SWELL.

TMI understand that the first time material from Pulp: A Short Biography of the Banished Book was exhibited was for Written in the Margins in 2017 at Künstlerhaus Bethanien, which came off the back of your residency at the institution. How has the project developed since then?

SRWritten in the Margins was a documentation of work in progress, made at a time when the research and filming were more immediately apparent as process rather than outcome in the exhibition space. It was not meant to be a complete exhibition of the project in and of itself.

The presentation at the Singapore Pavilion in Venice is a comprehensive, fully realised exhibition of five years of work, through text, drawing, film, and sound. Also, the footage in Written in the Margins only appeared as raw clips for the viewer to browse through, in keeping with the nature of the work as documentation, rather than as a cohesive, complete film.

The project has since evolved beyond process-based work, and beyond the regions and flashpoints explored in Written in the Margins in 2017.

TMConvergence and collaboration appear to be at the heart of this project, as reflected in The Wood for Trees, your solo exhibition at Objectifs – Centre for Photography & Film in Singapore in 2018 that tracked the texts, individuals, and locations that have formed it.

What has the project taught you in terms of new strategies for collaboration and access to information, and what new initiatives can you imagine for the future in terms of preserving cultural heritage?

SRAs I have journeyed through Pulp, reading, travelling, filming, listening, and writing about books, libraries, cultural production, violence, and resistance, there has been an almost-constant sense of being overwhelmed by material—stories, personal encounters, resonances, and contradictions.

Yet my capacity to be surprised has never diminished. Repetition, when it occurs, is not tedious but reaffirming, as when dissimilar people from vastly different milieus demonstrate a similar passion for a text.

Sometimes, strategies of self-organisation are developed independently of each other in respective communities facing cultural or linguistic extinction and end up being mutually beneficial because a new means of sharing is created.

These unexpected joys alleviate the sometimes-dire nature of this project and reaffirm the necessity of looking at books in such different ways.

And so the initial motivations for this project haven't changed, though they face constant review and reassessment. Positions and ideas have evolved, some were necessarily discarded while others have been validated, and there have been moments of displacement from personal anchors.

Pulp III serves as a midway marker of that evolution by revisiting some long-cherished notions now abandoned, and crystallising tenuous ideas into more clarified distillates. Given the decade-long nature of Pulp, it seems fitting that these nodes appear here like of-this-moment positions rather than unshakeable convictions.

TMWhat does this opportunity represent, in terms of exhibiting your work in a national pavilion?

SRBeing selected as an artist to represent the Singapore Pavilion is a significant honour. The Venice Biennale is one of the oldest and most prestigious contemporary art platforms and for many contemporary artists, presenting work at the Biennale represents a pinnacle in our artistic aspirations.

Being the first solo female artist to represent the Pavilion is also extremely heartening and provides hope for more diverse representation of Singaporean artists both at home and internationally.

TMIs there a connection to the loss of the language belonging to Italy's historical immigrants to that of the Kristang language in Singapore? What are the connections between immigrant communities in these two places?

SRBoth the Kristang and Cimbrian communities—in Singapore and Italy respectively—recognise a similar need to have younger people speak their language.

This is mainly so they can communicate with community elders, as language is essential for transmission of knowledge between generations. Community elders are living repositories of story and memory, especially since these histories often do not exist in official records.

Through my conversations with the people of these communities, I've found that there is valuable information in the language that have connections with philosophies, lives, and livelihoods, and in turn the stories of their ancestors.

Through Pulp III, I wanted to look at the mechanisms that often don't allow these languages to thrive, but to also be cognisant of how outsiders must consider their dealing with threatened cultures and languages. —[O]