Solange Farkas Reflects on 40 Years of Videobrasil

SPONSORED CONTENT | SESC_VIDEOBRASIL

Solange Farkas. Photo: Mariana Chama / Biennial Sesc_Videobrasil.

Solange Farkas. Photo: Mariana Chama / Biennial Sesc_Videobrasil.

'You might say Videobrasil and video in Brazil grew up together,' explained Solange Farkas, the founder and artistic director of the São Paulo-based Contemporary Art Biennial Sesc_Videobrasil, in 2015.

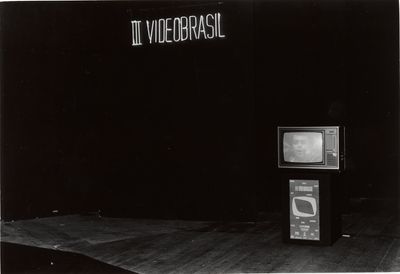

Videobrasil was founded in 1983 amid the demise of Brazil's military dictatorship, which rose to power in 1964 and ended in 1985 after José Sarney became the first civilian president of the republic. As Farkas noted, video back then 'was used more as a hybrid medium that related to all different kinds of expression, like performance, visual arts and cinema.' At its heart, it was a means to communicate during a period of intense political oppression. Unsurprisingly, 'censorship was strong', Farkas recalled. 'We had to show all the works to the censor before we could show them in the festival.'

Farkas soon established a refuge for a generation of Brazilian artists who began exploring video as a potent medium of expression, creating a platform to legitimise video in Brazil. But gradually, the event evolved into an international gathering with a global outlook. 'It was like a new reality,' Farkas recalls of that evolution's early years. 'We started to see how artists relate to the same things but from a really different local perspective, yet in a global sense.'

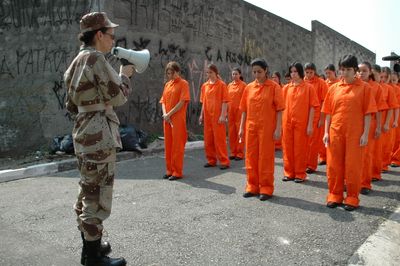

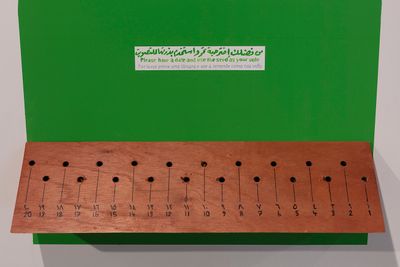

This global perspective has evolved significantly since Videobrasil made a conscious decision to engage with the geopolitical South in the 1990s. Then, in 2014, Videobrasil's 18th edition officially made Southern Panoramas the foundational theme of the event's entire programme. The central exhibition featured 94 artists from 32 countries, among them Akram Zaatari, Eneida Sanches, Mahmoud Khaled, Michel Zózimo, and Rodrigo Sassi, in addition to the exhibition 30 Years, celebrating three decades of Videobrasil.

A focus on the geopolitical South has continued for successive editions, with the festival's title changing to Contemporary Art Biennial Sesc_Videobrasil in 2019. The 21st Videobrasil, which ran between October 2019 and February 2020, explored how artists like Claudia Martínez Garay, Hiwa K, and Tang Kwok Hin poetically confront nationalism.

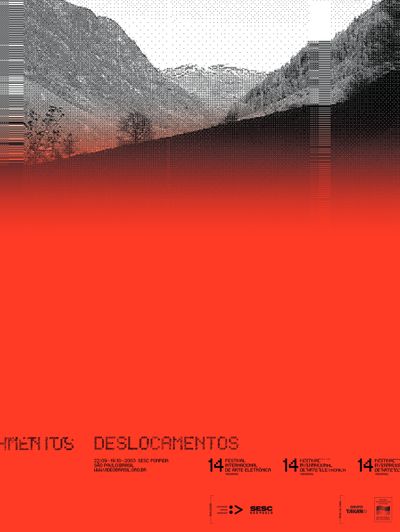

Now entering its 40th year, the 22nd Biennial Sesc_Videobrasil, Memory is an Editing Station (18 October 2023–25 February 2024), has been conceived as a space to reflect, both on Videobrasil's history and the emerging realities of a post-pandemic world.

Curated by Brazilian curator Raphael Fonseca and Kenyan curator Renée Akitelek Mboya, with artistic direction by Farkas, the exhibition's title quotes Brazilian poet Waly Salomão (1943–2003) from the poem 'Carta aberta a John Ashbery' or 'Open letter to John Ashbery', which interrogates strategies of recalling and archiving the past.

A central exhibition of over 100 works spans textiles, paintings, photographs, and videos by 60 artists and collectives from 38 countries, including Agnes Waruguru, Ali Cherri, Brook Andrew, FAFSWAG, Isaac Chong Wai, Nolan Oswald Dennis, Samuel Fosso, Tromarama, and Zé Carlos Garcia.

Accompanying the central show is 40-Year Special. This anniversary exhibition, curated by Alessandra Bergamaschi and Eduardo de Jesus, looks at four decades of archival materials and artworks from the Videobrasil Historical Collection.

'In the spirit of the verse by Salomão that gives the title to this edition, we re-edit our memories in the light of a new present,' Farkas says, who introduces Memory is an Editing Station in this conversation, and reflects on the institution's past, present, and future.

SBCould you share your interpretation of Waly Salomão's poem, which gives this edition of Videobrasil its title, and how it relates to this particular edition and its reflections on Videobrasil's history?

In 'Open Letter to John Ashbery', Salomão describes ability to edit our memories 'at the pleasure of [our] own convenience' through the screen, which you've touched on when describing the screen as something that 'crosses different visions and experiences because it is present not only in the context of the arts, but also in our daily lives.'

SFVideobrasil has never left video aside, even when the biennial opened up to all artistic practices. But we can say that in this edition there is a special emphasis on this medium, which is directly related to the beginnings of Videobrasil back in the 1980s. And it's interesting to think about how video is once again occupying a central place in all fields of culture.

It was video that connected us during the pandemic and it's also video that's at our fingertips every day, on cell phone screens and computers. So, nowadays, video comes in a new guise: as an extension of our lives and hands; as something that is familiar. This is very significant for Videobrasil, and 40 years later we see that video is taking the centre stage like never before.

Going back to Waly Salomão's poem, the verse that gives the biennial its title makes a lot of sense at the moment. Memory, as he says, is an 'editing station'. Each person can edit certain narratives from their own memories, perspectives, and narratives.

Waly was a great life partner throughout Videobrasil's history. He is part of our memory and inspired several of our actions. In the case of the 14th edition, he took an active part in the research and curatorial discussions and gave that biennial its title, Displacements (Deslocamentos). Waly was an extraordinary poet who inspired many artists—not only Brazilians, but also, and mainly, Lebanese artists, with whom he created a very strong link, aroused, in a way, by the connection with Videobrasil.

SBThe 40-year anniversary show has been curated to look back on Videobrasil's history while being in conversation with Fonseca and Mboya's exhibition and the Public Programs. In both cases, there is a re-evaluation of the history of video. What are some of the highlights of this 40-year show in terms of expressing that re-evaluation?

SFLooking back at Videobrasil's past reveals, paradoxically, a constant movement of listening to the future. 40-Year Special, which highlights our collection and the institution's long trajectory, makes sense because it tells us a lot about the present and, of course, it is in direct dialogue with the main, contemporary show.

Beyond the matter of media, technologies, and artistic support, the themes that Videobrasil has confronted throughout its history—such as colonialism, racism, Indigenous issues, gender, forced displacements, and conflicts around the world—continue to be urgent issues today. These themes, therefore, appear in both exhibitions, showing a coherence in the biennial through the decades.

It's also worth thinking that, in this context, the Videobrasil Historical Collection is extremely important. It is the source of fruitful and revealing curatorial, poetic, and historical articulations, which extend themselves in many directions across time and space. The compendium of artworks, documents, publications, and testimonies gathered around Videobrasil is increasingly central to our curatorial and research activities, and to our outlook as an institution.

If what motivated the initial creation of the compendium was the urgency of preserving works produced in fragile electronic media, today we see this effort as something that goes far beyond technicality. Preserving this history for future generations means looking at the Collection as a memory project in the making, which brings places and times into dialogue while seeking its relevance in the present.

SBYou told me in 2015 that the concept of video was fluid when Videobrasil began, incorporating performance and visual art as 'the preferred medium of the time'. Back then, you said, it was more about creating space for expression and communication in the context of Brazil under dictatorship, when civil society was increasingly agitating for democracy.

How has your understanding of video as a political tool for communication and an artistic medium shifted since then? Did Brazil's more recent history under the Bolsonaro regime and the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic shape your reflections?

SFWhen we think back to the beginning of Videobrasil, we are talking about a very particular political context, with the collapse of a dictatorship and the fight for democracy. We had only a few TV stations, which either agreed with the political power of the time or were censored. And video emerged at that time as a revolutionary tool: a medium that could capture reality and immediately show it. It was a very powerful means of communication.

Perhaps this is one of the great virtues of video: I record you and immediately I can show it. This had an impact all over the world, not just in Brazil, but when it happened here it provoked young people, especially young people who didn't come from the world of visual arts, who were interested in communication. Video didn't have all that apparatus of cinema, and was still seen as an inferior medium in the art world, so it wasn't intimidating. It could navigate places, question, disturb.

In this way, directors from the 1980s—realizadores, or realisers, a term used at that time to refer to young filmmakers who were not exactly directors but created films—used video as a political gesture. They tried to get on television and discuss issues that were not widely discussed at the time. With video came television in the street: of television showing people talking to people...

Jumping forward to the present day, during former Bolsonaro's administration it seemed that, unfortunately, we were revisiting a moment we experienced in Brazil back in the dictatorship era. In recent years, it seemed impossible to plan any project in the face of a government that disrespected, attacked, and even eliminated culture, which included the press and democratic institutions, in a clear flirtation with totalitarianism. Then there was the pandemic, which was at first paralysing, also due to the tragic governance in Brazil, a political situation that made the issue much worse.

We now have a renewed political environment that, in the end, is seeking to deal with the human rights losses of recent years. In that context, our resolve to research, present, and make available to everyone—whether through the Biennial or the Collection—the visual arts production of a region of the world known as the South, has only increased.

Looking back over these 40 years, it's clear that the political DNA of video is still present, and is being used more and more—even by artists who don't come from the audiovisual world, who have always used other languages, and now realise the power of video.

SBVideobrasil made a conscious shift towards focusing on artistic practices from across the Global South after years as a festival that centred on Brazilian contemporary art, a position that has become stronger with each edition. Could you talk about how you perceive that shift now?

SFWhile there are major issues that connect us—such as the colonial past that connects many countries, for example—the great wealth of the South lies precisely in this enormous diversity of cultures, languages, ways of life, and worldviews. What we have always emphasised, which is also in line with the changes in the curatorial sections throughout the history of the biennial, is that the concept of the Global South is not static. It adapts to specific international contexts and it changes over time, just like the global economy and geopolitics.

Thinking back over Videobrasil's history, we moved in this direction early on. Even at the turn of the 1990s, I thought that simply holding an international festival was definitely not going to work in a positive way. It could have the opposite effect, because if video production in Northern countries was already much more advanced, Brazilian artists would not stand a chance in a competitive show with awards, which is a way of stimulating production.

It was thus necessary to show and bring artists from places similar to Brazil, which have experienced similar political and even geographical—but much more political and cultural—conditions, in order to see how we can talk to each other. And that was a very wise choice. Over time, we have created this huge network of connections with artists, institutions, and audiences around the world, and we have achieved this with empathy. I'm very proud of these 40 years, especially when I see how these relationships provoked by Videobrasil continue to evolve.

I feel that what we're seeing in the arts can also be seen in the geopolitical sphere: a growth in the strength of the countries of the South. It's noticeable that for some time now, the global art world—Europe and the USA, et cetera—have been looking at the so-called 'peripheries' more. We see curators travelling to the South, looking for other types of production created by groups that have been previously underrepresented but are now gaining ground.

This is something recent, historically, and I've always felt that we as an institution needed to be prepared for this moment, because this relationship needs to be balanced. As an institution, we have long supported projects, artists, and artworks that are not necessarily sanctioned by the established circuit and the market.

One statement for this edition tells us that participants live in the South or have 'settled—whether by intent or necessity—in major Western centres.' This acknowledges the complex experience of globalisation by artists who find themselves being criticised for living and working in the West while claiming the South as their identity. It's the kind of complexity that recalls something we discussed in 2015 regarding Brazil's historical role as both coloniser and colonised.

How has working with Videobrasil sharpened your own positionality within this context?

SFThe concept of the Global South has always been changing and even includes territories internal to the central countries. It's a political South, not exactly a geographical one. It's not cutting the globe in half. And this is also reflected in the diversity and plurality of this vast universe that we look at and work with.

The idea of the Global South has revealed an original way of thinking that operates from its own parameters, needs, and realities, vocalising a fundamental dissent from the established axes of art and unveiling the power mechanisms implicit in the way we are used to mapping the world. The artistic circuit created from this South has given visibility to practices that advocate protagonism and confronts issues ranging from social inequality to racism, from gender issues to the genocide of native peoples. In other words, the South is a diverse place, sometimes difficult to access, but with extraordinarily powerful histories that concern us.

SBLooking back to when you founded Videobrasil and where the institution is now, how have your ideas around the institution evolved?

SFVideobrasil emerged as a video festival in the 1980s which, even with its many peculiarities, was somewhat similar to the format of film exhibitions, with screenings and a competitive show. Over time, it has changed and adapted to the political, technological, and cultural context of a rapidly changing world. Along the way, we made choices that were questioned a lot, such as betting on video and prioritising our focus on the Global South, but these choices have proven to be very right.

Today, we no longer have to fight for the acceptance of video and production from this region of the world. We have created various international networks, starting with the foundation of the cultural association in the 1990s. Throughout the 2000s, we established ourselves as a contemporary art biennial. In other words, we have been in constant transformation, but we have always maintained a spirit that has existed since the beginning, of not choosing the obvious or already established paths. And it's been an intense battle, not always easy to take on.

That said, our main focus from now on is on working with the Collection, activating it, making it publicly available, and preserving it. With more than 3,000 works, as well as a large number of documents, publications, and statements by artists and curators connected to Videobrasil, our compendium is certainly one of the most significant of its kind in the world.

Working on this 22nd edition has deepened our sense that safeguarding this compendium is an enormous responsibility, especially in a country marked by a chronic absence of consistent policies for preserving cultural heritage. —[O]