Politics and Aesthetics at the 11th Berlin Biennale

Exhibition view: exp. 2: Virginia de Medeiros – Feminist Health Care Research Group, 11th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art, ExRotaprint, Berlin (30 November 2019–8 February 2020). Courtesy Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art. Photo: Mathias Völzke.

Before opening its main exhibition (5 September–1 November 2020), the 11th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art, The Crack Begins Within, began its programme one year ago, in September 2019, with three 'experiences' comprising exhibitions, lectures, workshops, screenings, and performances.

These warmup presentations—referred to as exp. 1, exp. 2, and exp. 3—anticipated the exhibition's 'epilogue', which opened on 5 September 2020, with the aim to 'learn from and build sustainable relationships, not only with participating artists and projects but, just as importantly with the city and people of Berlin.' They were held at the ExRotaprint space in Wedding, the smallest of the four Biennale venues alongside KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Gropius Bau, and daadgalerie, and paved the way for a main exhibition that responds to a variety of planetary concerns, from climate change and the rise of populist right-wing governments, to LGBTQ struggles, and the fight against patriarchy and male violence.

With 'unrehearsed uprisings of beautiful rage' unfolding across the world, this Biennale 'began by asking how to celebrate the complicated beauty of life as the world burns around us', write the female-identified South American curatorial team consisting of María Berríos, Renata Cervetto, Lisette Lagnado, and Agustín Pérez Rubio. If redressing injustices is a goal of this edition, the lack of big-name, blue-chip artists is this exhibition's first noticeable gesture, with the exception of two early 20th-century figures.

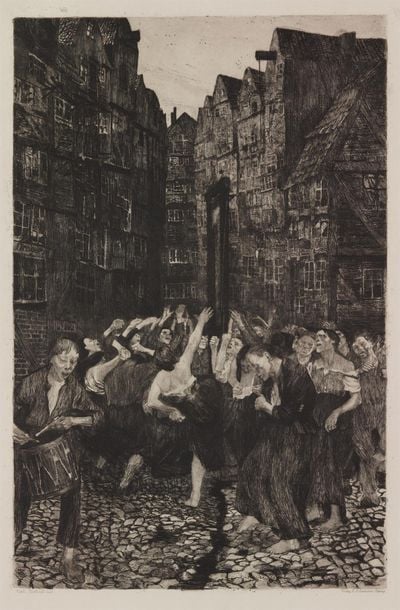

The German political artist Käthe Kollwitz is represented with a series of works at KW Institute for Contemporary Art, including Die Carmagnole (The Carmagnole) (1901)—accompanied by its test print—a black and white image depicting an angry congregation of predominantly female demonstrators foregrounding an urban environment. Female-led rebellion continues in prints such as Charge (1903), from the artist's series, 'The Peasants' War' (1903–1908), which depicts a woman, inspired by the 16th-century figure 'Black Anna', who is cited to have instigated the German Peasants' War, arousing peasants into revolt.

Among works on show by Nobel Prize-nominated Brazilian artist and architect Flávio de Carvalho is a booklet documenting de Carvalho's famous 1931 performance, Experiência no.2, realizada sobre uma procissão de Corpus Christi (Experience no.2, realised on a Corpus Christi procession), in which the artist walked against a crowd of worshippers in a religious procession.

The rest of the exhibition is organised around works by lesser-known artists, most hailing from the so-called Global South, with bright colours, sharp outlines, and depictive techniques defying modern and conceptual aesthetics punctuating the show.

At KW Institute for Contemporary Art, a selection from Filipino artist Brenda V. Fajardo's well-known tarot cards series from 2018, 'Baraha ng Buhay Pilipino' (Cards of the Lives of the Filipinos), pictorially retells the history of the Philippines. Continuing this historical tracing is the work of Cian Dayrit at Gropius Bau. Tropical Terror Tapestry (2020) is a large tapestry depicting the continuing violence, militarism, and corruption of the country's army against rural and indigenous communities in comic book style.

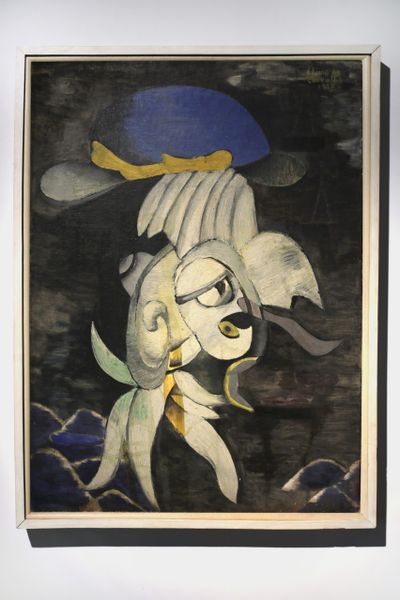

Occupying a large part of KW Institute for Contemporary Art's main exhibition hall is an installation of several works by the late Brazilian artist Pedro Moraleida Bernardes, whose brief life ended with suicide at 22 in 1999. Influenced by Antonin Artaud and Bispo do Rosário, his disturbing images seem to belong to the context of the Latin American culture wars of the 1990s between postmodernists and the church, blending violent sexual images with biblical references.

With 'unrehearsed uprisings of beautiful rage' unfolding across the world, this Biennale 'began by asking how to celebrate the complicated beauty of life as the world burns around us'.

Sentindo um cansaço mortal por representar o humano, sem fazer parte do humano (Feeling a deadly weariness of representing humans while not being part of humanity) (1997) involves framed paintings erected like a three-headed cross depicting images of beasts and humans having anal, oral, and vaginal sex in front of large black crosses, with a dark void with floating body parts comprising the middle bulk of the work.

While conveying distinct aboriginal or ethnic forms with various political or spiritual content against the domination of what the curators consider hegemonic cultures, the exhibition's strength lies in a universal affinity between forms and contents, which different geographic, political, and artistic contexts share—consciously or unconsciously—in order to put their messages across globally.

Interestingly, works by those whose practices extend beyond the visual arts stand out as extraordinary documents of the human condition. Such is the case with Kurdish activist and journalist Zehra Doğan's drawings, presented as an archive on a double slanted table and behind glass at KW Institute for Contemporary Art.

Taking the form of a graphic novel, 'Xêzên Dizî' (The Hidden Drawings) (2018–2020) tells the story of the Kurdish struggle for independence from the point of view of those who have been incarcerated by Turkish authorities. They depict unsettling scenes of interrogation and torture, but also beautiful moments between women from different generations gathering to share experiences in prison.

Thrown into jail in 2017 and accused of supporting terrorism when one of her anti-government graphics depicting the Turkish government's German-made tanks toppling Kurdish homes in her town Nusaybin as scorpions went viral online, Doğan's accompanying words describe the conditions imposed on political prisoners held captive by the Turkish state for years, if not decades.

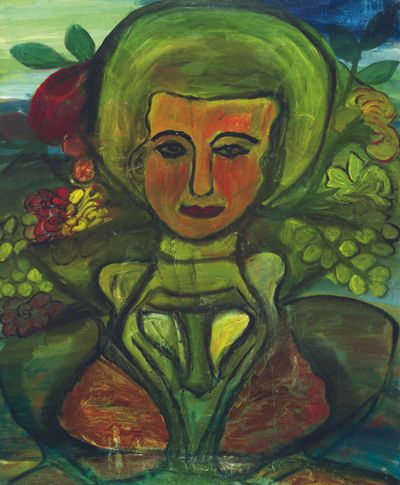

As part of the Museu de Imagens do Inconsciente and Museu de Arte Osório Cesar's installations at Gropius Bau, works by mental patients created in response to the therapeutic practices of Brazilian anti-psychiatry physicians Dr. Nise da Silveira and Dr. Osório Cesar are on display. In 1933, Dr. Cesar collaborated with the artist Flávio de Carvalho to organise The Month of the Children and the Mentally Ill at the Clube dos Artistas Modernas in São Paulo, presenting what they considered to be pure art untouched by the ideas stemming from the art academy.

Dr. da Silveira's patients, Carlos Pertuis and Adelina Gomes, were prolific non-artists, but nevertheless practitioners, each producing thousands of works during their lives, some of which are presented in the exhibition. In one untitled work by Pertuis from 1950, a group of men wearing white shirts, blue pants, and black fedoras are depicted ritualistically gathered around a machine-like structure with steel legs and a blue flame-like head attached.

Works by Gomes, a black working-class patient, focus mostly on her inner life through the medium of self-portraits, often showing the artist in the process of becoming one with her surroundings, either through her integration with the flora and fauna in the background as in an untitled work from 1962, where the outline of the figure's head appears blurred, as in further works from 1964 and 1967.

While on some level too conveniently used as placeholders for the anti-conceptual aesthetics advocated by the curators of this Biennale, these imaginative works are richly connected to those of Kollwitz and de Carvalho, not only due to the sincerity with which they have been produced, but also as therapeutic interventions affecting real lives beyond the world of art.

But even if art has real-world consequences, that should not disarm the field from critiquing itself, especially when it comes to making much-needed distinctions between aesthetics and politics while acknowledging their codependency.

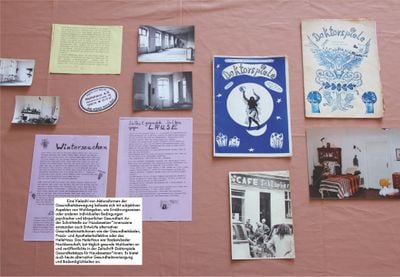

Nowhere in the exhibition is the need for bifurcating aesthetic forms from their political content more obvious than in the case of the Feminist Healthcare Research Group, made up of artists Inga Zimprich and Julia Bonn. Building on the 1970s truism popularised by Carol Hanisch, that 'the personal is always political', the duo, starting from their own conversations as mothers, has been researching the 1970s and 80s West Berlin health movement, and the role of feminist health initiatives throughout this period.

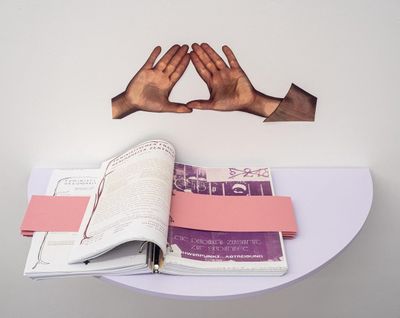

The collective presented their research in a series of events and archival displays during exp. 2: Virginia de Medeiros – Feminist Health Care Research Group at ExRotaprint (30 November 2019–8 February 2020), which culminated in the publication, Being in Crises Together Vol. 2.

The Feminist Healthcare Research Group's research—which is anchored to anti-discriminatory practice—makes it clear that the idea of health is social, political, and psychological: a fact that rings truer today as the ramifications of the global Covid-19 crisis unfold.

Yet their introduction to Being in Crises Together Vol. 2 raises some issues when it comes to distinctions and relations between aesthetics and politics. In a concluding note, the collective discusses their use of language in the text, choosing to 'write Black and PoC (People of Color) with capital letters to refer to them as self-representations', 'white in italics to point at whiteness as a construct that privileges white people in the framework of white supremacy', and 'binary gender categories like women* and men* with an asterisk, in order to underline their social construction.'

While in complete agreement with the epistemological shifts that inform such aesthetic declarations, there is something naïve or perhaps even counterintuitive about this type of typographical activism in the 2020s.

Those familiar with social movements of the 1980s and 90s will remember that people striving for equality and justice had to learn that not everything personal is political, and short of real political struggle in all levels of social life, a mere shift in language does not automatically produce emancipation and could even cause resentment and incite resistance, which connects with this Biennale's political stance as a space of global resistance against forces of intolerance and bigotry.

But despite the shortcomings that an overemphasis on the primarily political role of art might entail, the 11th Berlin Biennale is the exhibition that Berlin needs in the current climate. The neoliberal forces that have been at the helm of policy and power in Germany and the European Union more broadly might not be successful in pushing back against the cascading enclosure they feel by the forces of neonationalism and at the ballot box, but they can use their institutional clout to put on a show of confidence, if not force, in an ongoing culture war.

But only history can tell if returning to Walter Benjamin's old prescription of politicising aesthetics against the fascists' attempt to aestheticise politics will win the day for progressives.—[O]

![Brenda V. Fajardo, Alaala ni Erol, Bens, Julia, Jake atbp. Maging Matatag, Huwag Sumuko! (Memory of Erol, Bens, Julia, Jake, and Others. Be Courageous, Do Not Surrender! [People who took their lives]) (2018). Coloured ink on paper. 28.3 x 40 cm.](https://files.ocula.com/anzax/Content/Reports%2F2020%2FBerlin%20Biennale%2FBrenda-Fajardo_400_0.jpg)