16th Istanbul Biennial Collapses Culture-Nature Divide

Marguerite Humeau, Venus of Courbet, An 80-year-old female human has ingested the brain of a swallow (2018). Bronze, a cappella voice. Exhibition view: The Seventh Continent, 16th Istanbul Biennial, Istanbul (14 September–10 November 2019). Presented with the support of Institut Français and British Council. Courtesy the artist and C L E A R I N G, New York/Brussels.

At the opening of the 16th Istanbul Biennial, The Seventh Continent (14 September–10 November 2019), curator Nicolas Bourriaud began his introduction with a clip from Werner Herzog's 1982 movie Fitzcarraldo, the story of a man who moves a steamship up a hill in the process of fulfilling a fantasy to build an opera house in the Amazon jungle. The plot was inspired by historical events, albeit with a less romantic pursuit (an aspiring industrialist sought the riches of Amazonian rubber). The film became a feat of life-threatening labour (and for some, outright exploitation), with cast and crew actually transporting a 360-tonne vessel up a 40-degree jungle slope.

Apparently, says Bourriaud, Herzog predicted at that time that the Amazon rainforest would disappear within 30 years—an observation that does not seem so far-fetched with the fires that have raged through it this year.

Bourriaud went on to relate Fitzcarraldo to what happened just before this Biennial's launch, when asbestos was discovered at the historic Haliç shipyard, the show's main location. Some 40 projects were moved to the Antrepo 5 warehouse, now the Painting and Sculpture Museum of the Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University, making this the first Istanbul Biennial to change venue due to environmental reasons; a fact, Bourriaud points out, that connects to the curatorial theme, which is anchored to the mass of waste floating on the ocean—a 'drifting continent' that has now firmly entered the food chain.

The exhibition's visual identity illustrates this accumulative material plane; debris is mixed with floating satellites, solar panels, and emoji—a reflection of the dense landscapes assembled for this exhibition, in which distances between time, space, and being become immediate. Mika Rottenberg's single-channel video Spaghetti Blockchain (2019) connects scrolling Instagram aesthetics (a hand slicing brightly coloured jelly rolls against pop-colour backrounds, for instance) to the deep time of the Mongolian plains, and the vibrations of a throat song with the hum of a server farm. While Dora Budor's 'Origin' series (2019) abstracts the longue durée of environmental decline into a series of dust chambers into which sounds from renovations nearby are transmitted, activating particles and pigments that reference the peach hues of painter J.M.W. Turner's polluted 19th-century skies.

As Bourriaud underscores, The Seventh Continent is not so much an ecological show as it is a post-cultural exhibition that 'acknowledges and addresses the end of the division between nature and culture'—a submergence into the current 'ecological catastrophe' in order to reflect and understand 'how the Anthropocene has modified . . . modes of perception'.

The motif of nature is constant, but its expressions shift and morph among the works included by 56 artists and collectives. At the Pera Museum, 19th-century illustrations taken from the book Art Forms in Nature by scientist Ernst Haeckel, founder of the study of oecology (the relationship between living things), offer the most traditional entry point. In the same venue, nine annotated illustrations from 2013 by Luigi Serafini embody a point of departure—studies of imagined lifeforms, described using an invented language, drawing on Serafini's 1981 Codex Seraphinianus, an encyclopaedia mapping out a world of the artist's imagination. At Antrepo 5, archival giclée prints from Suzanne Treister's installation HFT The Gardener (2014–2015) diagram the nature-culture collapse on neoliberal terms, grouping flora under names of companies listed in the Financial Times Global 500 Financial Index, like Pfizer, PetroChina, and Apple.

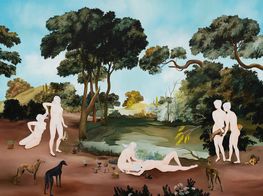

Throughout, archaeologically inflected assemblages sketch out narratives that move between fact and fiction. Claudia Martínez Garay's The Creator (2019) lies on the historical end of the spectrum, with 20 clay objects referencing the cosmology of the Moche civilisation, which disappeared as a result of flood and drought around the 1st century A.D. Warriors and animal forms based on items looted from Peru and sold to museums abroad emerge out of a mound of dirt dotted with printed aluminium cut-outs of plants. A more speculative projection is Marguerite Humeau's Venus of Courbet, An 80-year-old female human has ingested the brain of a swallow (2018): an anthropomorphic bronze sculpture positioned against a column in a dark room, in which the sound of chanting voices points to a hypothetical history about a group of women who tried psychoactive substances some 150,000 years ago and changed the course of human evolution.

Müge Yılmaz's installation Eleven Suns (2019), meanwhile, presents a mashup of aesthetics drawing from various references, both primordial and contemporary: a circle made of stones and water containers in the centre of the room is surrounded by hand-carved birch forms of plant-human-animal hybrids lining the walls.

Snakes appear to be a common thread in The Seventh Continent; an expression of a core theme in Bourriaud's show, which is admittedly uneven, with a noticeable lack of indigenous practices despite the curatorial's proximity to indigenous ideas. (There are references, like En Man Chong's 2018 video installation Ungrounding Land – Ljavek Trilogy, which charts the struggle of indigenous communities in Taiwan who relocated to the cities in the 1950s and participated in their construction, only to be classed as illegal settlers decades later.)

Time is deep, enduring, and open to interpretation, much like the symbol of the serpent across cultures. At Pera Museum, a clay snake hangs on the wall in Sanam Khatibi's presentation I dreamed I stabbed you in the eye (2019), which is centred around a large woollen tapestry depicting a pastoral scene in which white figures engage in Cain-and-Abel-like violence. At Antrepo 5, a grouping of works by Jennifer Tee includes a floor piece composed of snakes made out of clay, clustered together as if to form a carpet (Lines Swirls Bones, 2018). Hung on the walls in this room are collages inspired by Sumatran tampan and palepai textiles made with pressed tulip petals, with geometric patterns expressing the procession of souls to the afterlife.

In such framings, the snake is an enduring form that evolves as time accumulates, with narratives, symbolisms, and species added to its changing and expanding structure; a material reality composed of cells, facts, and fictions that jostle and collide with one another in a manner recalling the material mass, at once solid and fluid, after which this show is named.

Drawing these elements together is Ursula Mayer's Atom Spirit (2017), a film set in Trinidad & Tobago that follows a group of evolutionary geneticists collecting and cryogenically freezing DNA to create a frozen Ark, in which the concept of the afterlife becomes an imagination of a future world and what will become of those who will be shaped by it. In one scene, the group dances together, the snake appearing again in the form of a patterned catsuit worn by one character. 'DNA's micrological architectures are interfaces and interactions forming the foliage of fractal geographies', the narrator proclaims in one scene—'the lattice work of exponential entanglements'.

The body is a latticework within this latticework: an organic form that could be described as the sum of its parts among all others. Visualising such connections are works like Turiya Magadlela's pantyhose tapestries covering the walls of a room, conveying the experience of female bodies in oppressive patriarchal systems; and Rashid Johnson's stunning video The Hikers (2019), in which two masked men encounter one another on a hike, and engage in a ballet about the intimacy, trepidation, and recognition that comes when strangers meet and reveal themselves.

In fact, affective encounters happen throughout The Seventh Continent, whether in Jonathas de Andrade's O Peixe (The Fish) (2016), which films Brazilian fishermen from Piaçabuçu and Coruripe soothing their daily catch as they die in their arms, or in Glenn Ligon's screening of Sedat Pakay's short film From Another Place (1970) on Büyükada Island, which documents James Baldwin's time in Istanbul, with Ligon overseeing the inclusion of Turkish subtitles for the first time.

In Korakrit Arunanondchai's video, with history in a room filled with people with funny names 4 (2017), the post-apocalyptic worlds of a humanoid rat and a drone spirit named Chantri are brought into that of the artist's aging grandmother, at a time when Donald Trump came to power and the king of Thailand passed away. 'The undoing is soft and light', the narrator notes in one scene, as the artist's grandmother smiles at the camera, her hands clutching at a walking aid as she moves forward. It is a moment of staggering vulnerability; life as a natural drift in one direction. —[O]