Chinternet Ugly at Manchester’s Centre for Chinese Contemporary Art

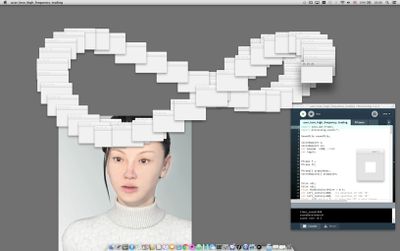

Ye Funa, Beauty Plus Save the Real World (2018). Exhibition view: Chinternet Ugly, Centre for Chinese Contemporary Art, Manchester (8 February–12 May 2019). Courtesy Centre for Chinese Contemporary Art. Photo: Michael Pollard.

China, home to 802 million internet users, is subject to sophisticated online censorship. This shrouded state of affairs, unsurprisingly perhaps, serves to reinforce stereotypes around conformity elsewhere.

Any realm, digital or otherwise, subject to such strict scrutiny must necessarily be bland and uncritical, right? I was mulling over such Western preconceptions when I visited Chinternet Ugly, an exhibition at Manchester's Centre for Chinese Contemporary Art (CFCCA) (8 February–12 May 2019), co-curated by Dr Ros Holmes, presidential academic fellow in art history at the University of Manchester, and Marianna Tsionki, research curator at CFCCA.

Staged across three separate gallery spaces, six artists—each belonging to the country's first generation to grow up with access to mass online digital platforms—engage with the Chinese internet, otherwise known as the Chinternet, a world unto itself, in clever and subversive ways.

In gallery one, Liu Xin draws on her roles as artist and engineer to fuse scientific research with personal narratives, exposing the sometimes-binary relationship between online and 'real'. For Can you tear for me? (2015) Liu asked online workers (via MTurk—a marketplace where work can be outsourced virtually) to upload images of themselves crying.

Here, those images—analogue rather than digital—are pasted on the gallery wall. The result is peculiar. Though shown physically, they are every bit as flat as they would be if they were to be viewed on screen. In a small vitrine nearby is When is the last time you cried? (tear bottle for online exchange) (2018–2019)—a number of vessels purporting to contain tears, which are in fact made from a chemical concoction which, so the wall text tells us, 'mirrors the composition of the artist's own biological fluid'.

Similarly exploring the distance between the manufactured and what is actually there, is Ye Funa's colourful, pink-hued installation Beauty Plus Save the Real World (2018), which engages with China's most popular selfie-enhancing app, Meitu Xiuxiu. The platform holds the world's largest facial database with a staggering 1 billion images; a reality that Ye seems to reflect on by installing freestanding human-height transparencies within the gallery, perfect to frame the figure, with sculptural props and mirrors installed on walls covered in bright, pink-hued wallpaper, emblazoned with empty-sounding empowerment platitudes, and a neon sign that reads 'EXHIBITIONIST'.

In today's camera-ready culture, it is unclear whether this selfie set design is a criticism or a celebration—an invitation for viewers to have fun, or to add to Meitu Xiuxiu's facial database. On the floor, a large transparent plastic mask with holes for eyes, nose, and mouth looped with neon tubing points toward an answer (in case, deep down, we didn't already know): a criticism of vapidity executed with a smile.

The knowing smile in Beauty Plus Save the Real World seems to be given voice in aaajiao's I hate people but I love you (2017), which places us in uncanny valley territory. Occupying a Mac OS backdrop, an archetypal 'female Asian android' and a part-mesmerising, part-maddening loop of pop-up windows take part in a conversation, if one can call it that.

The deadpan delivery and limited nature of the back and forth—with phrases like 'Do I look real to you? I hope so', and 'I hate people, but I love you'—is intended to reflect our need for connection through the barriers of screens and layers of online personae. These blank monotone utterances produce a sense of foreboding that brings to mind the malign HAL 9000 from Arthur C. Clarke's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), a sentient spaceship's computer who jeopardises the safety of its crew.

The question of the future is imagined as a time of obsolescence in Lin Ke's single-channel video installation I'm Here (2018); in this case, when people no longer use the computer mouse, rendering the ubiquitous image of the cursor meaningless. The film is intentionally (I think) mundane; we see a trio standing in front of a video in a gallery, with nothing much happening. In one scene, a viewer photographs the work in front of them on their phone.

This event occurred just as I was taking a picture of the video, creating an odd doubling effect of the phone in the hands of the figure I was watching on the screen in front of me, and the device in my hands—a reflection not only of the time we waste passively scrolling online, but of the passive looking that screens engender, in which a level of remove obstructs a true experience of life, action and, perhaps, intent.

The hyperreal, glorious Technicolor of Lu Yang's video installations Electromagnetic Brainology (2018) and God of the Brain (2017) provided a much-needed jolt to such a monotonous reality. With strong protagonists, ritual dance, soundtrack, and assorted accoutrements (including the brains that each work's title references), the films are a mash-up of religious iconography, as well as the heroic imagery found in video games and anime.

Lu's intoxicatingly lurid works pose a number of questions. What do we worship? When, why, and how did these objects and figures of worship change? Proving the point that rational thinking can be quickly jettisoned when confronted with the stimulation of music and bright colours, much time could be lost gawping at the action in both works.

In contrast, Miao Ying's video Love's Labour's Lost and wooden sculpture, Love's Little Wall (both 2019) in gallery two, are modest, quiet pieces. Captured in Paris, Europe's 'Capital of Love', Love's Labour's Lost sees the artist unpick so-called love locks: a metaphor for the practice of employing VPN (virtual private network) servers as a means of getting around the restrictions of the Chinese-only internet to access the open global version.

The sculpture, however, incorporates lovelocks onto a mini Great Wall of China: a signal, perhaps, that walls—no matter their form—can be overcome, one way or another. —[O]